Patricia Highsmith, whose centenary falls on January 19th this year, has become perhaps one of the most influential writers of all time, with her slick twisted dark tales helping to form the foundation of the modern “psychological thriller”. Novelist and critic Gary Raymond takes a look at what makes her work stand out from the rest.

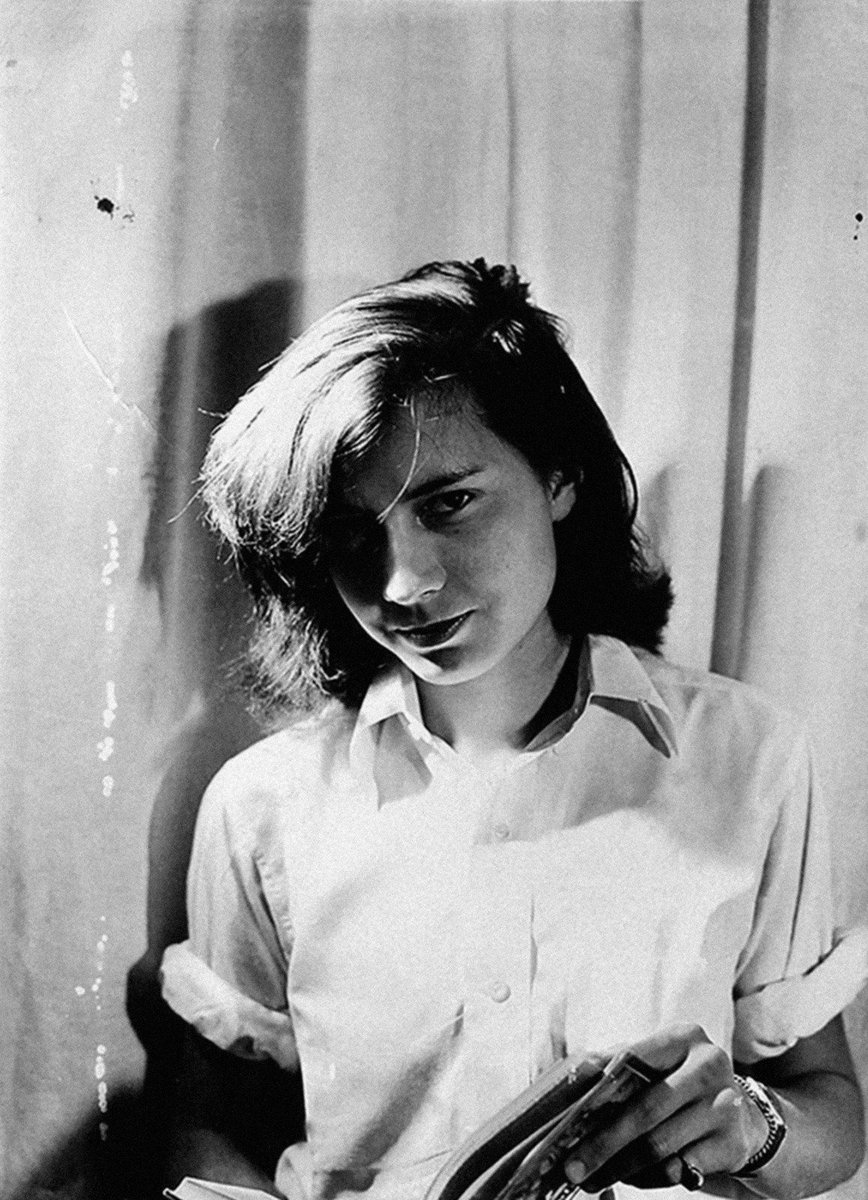

There is a photograph of Patricia Highsmith, famous to those who have ever been interested in her, taken by her friend (and would-be suitor) Rolf Tietgens when she was twenty-one. She is beautiful, yes, and has the look of a very intelligent, prepossessing young woman. But there is something else in that slight upturn of the mouth – you can barely call it a smile – and the twinkle in the eye. Her hair is mussed and pushed to one side. The shadows across her face feel like they are utterly under her control. But you keep coming back to that expression. Mona Lisa, darkness and light, that look she is holding in the centre of the lens, impossible to define; as biographer Joan Schenkar says of Highsmith in it, she has all the allure of the garçonne. I’d go further: it’s as if she’s holding the inescapable excitement of what it is to read all those dark, sadistic books she will ever write in that single frame. It feels facile to say that in that glance you get how she broke the hearts of so many who fell for her, but somehow it also feels important to her story. Patricia Highsmith, who ended up going on to have something of a reputation for being difficult if not out-and-out misanthropy, was an obsessive whose primary preoccupation was with the darker impulses of the human state. She was interested more in that than she ever was in people, and her dedication to and obsession with these Dostoevskian depths is what made her such a mesmerising writer. And somehow, you can see it all in that photo.

The Dostoevskian influence has been thoroughly investigated by scholars and biographers, and not least by Highsmith herself in her copious notebooks and journals. He was the writer who spoke to her with the clarity to unlock her writerly vision, to open up her own depths and bring them to fruition on the page. Or to put it cleanly, he gave her access to what we now call the “voice”. Her Dostoevskian streak was also keenly modern, which is what has always made her so attractive to filmmakers, and Strangers on a Train, her first published novel in 1950 (and filmed by Hitchcock in ’51), owes as much to Leopold and Loeb as it does to Raskolnikov. Her approach to plotting is hardly akin to any of the Russian masters. She spent the 1940s writing for comic book companies, and mentions in her diary in December 1947 how she just failed to get a gig writing Wonder Woman.

Patricia Highsmith ended up shunning America. She never sold as well in her home country as she had done abroad. She said that readers in Europe understood her better, but perhaps it was more to do with the fact she was able to understand herself better on the continent of Dostoevsky. It’s he who threads himself through her work more than any other writer. Schenkar has said of Highsmith that she wasn’t a “crime” writer, but a “punishment” writer. It might be too neat to say that Highsmith’s first serious affair was with the ghost of Raskolnikov, but I think you’d certainly, at least, be on to something. But the difference in Highsmith and Dostoevsky might be that Dostoevsky was formed by the political realities of his time, as well as the dominant themes in Russian literature and philosophy. By the time he published his first novel, Poor Folk, in 1846, when he was twenty-five, Dostoevsky had already written to his brother of the naivete of his youthful ideals when he believed the world to be “full of very noble men.”

The dominant theme of Dostoevksy’s novels can be seen in Highsmith’s too, but the suspicion, as Schenkar aligns herself with, is that Highsmith found in Dostoevsky’s work a kindred obsessive. Dostoevksy did not sculpt Highsmith, rather his work invigorated the personality that had been apparent in her since she was a child. Raskolnikov’s obsession in Crime and Punishment is in “becoming… a Napoleonic personality and acquiring homicidal privileges” (as Joseph Frank puts it). Highsmith seemed to think such privileges could be earned with much less trouble than Dostoevsky suggests. Schenkar affirms these suspicions in her wonderful book, The Talented Miss Highsmith (2009).

When addressing Highsmith’s list in one of her notebooks, the ways children could murder their parents, Schenkar writes that “it leaves no particular sense that she meant it as a joke, but she must have… mustn’t she?”. The list itself is straight out of the headspace of Raskolnikov, albeit perhaps in a universe where he is more open to the creative potentialities of black comedy. The list, titled “Little Crimes for Little Tots (Things around the house which small children do…)”, includes tying string across the stairs for adults to trip up; putting rat powder in the flour jar; and “setting careful fires, so that someone else will get the blame if possible”. Highsmith made that entry into her notebook in 1973, when she was fifty-two.

Raskolnikov may have wanted to be Napoleon, and I can’t think of anything that would have appalled Highsmith more than that, but she was clearly empowered by the idea that one of the most important writers of the modern era opened up the possibilities for exploring the battles between reason versus moral conscience. You could argue that Highsmith takes up where Dostoevsky left off. Many of Highsmith’s “psychopaths” are at the end of the journey that we join Raskolnikov on when Crime and Punishment opens. Crime and Punishment itself opens six months after Raskolnikov’s Damascene moment when he pens the essay “Crime” and possibly ends with murder. Highsmith’s characters are much further on than this. (maybe she was too, as a person). Charles Anthony Bruno in Strangers on a Train, Tom Ripley, David Kelsey in This Sweet Sickness; they, and others, are psychopaths of conviction when we meet them.

I think of that photo again.

Highsmith always upends expectations. Nothing goes where you think it might on first encounter. There is an interview between Highsmith and Mavis Nicholson from the late 1970s that you can watch on YouTube. Nicholson is one of the great interviewers of the age, an artiste of the medium, from the school of conversationalists. But it’s an awkward affair, as if Nicholson isn’t really into it. She seems to go through a series of box-ticking “writer” questions – When did you first know you wanted to be a writer? What have you thought about the movies made from your books? That sort of thing. And Highsmith seems to be doing her best with them, being neither difficult nor impolite, although admittedly she’s not effusive, either. Schenkar describes Highsmith’s typical posture as “braced against embarrassment”, and it’s evident here. So, we have a personable Highsmith and a disengaged Nicholson. It doesn’t feel right, like they’re both acting against type. Like they’re up to something.

The most tedious question, the barrel scraper, seems to put some wind in Patricia Highsmith’s sales. The question about routine. Highsmith says she likes to get eight pages done a day, “ten if it’s a short story”. Nicholson moves on. Typewriter or longhand? Now, this is a question from a faraway land, and it’s not asked as much now we live in the “digital era”. But back then, this was a staple of the “phone-it-in” round of questions for any interviewer. It’s a lazy question. They’ve all been lazy questions. But Nicholson is not a lazy interviewer. And she’s not uninterested in Highsmith. She admits to having read all her books. So, there is another use for these tools. The questions are disarming. It’s the easiest way to butter up a writer’s ego, offer the pretence that you’re so interested in their art you want to know exactly, precisely, how it’s made. It’s now Highsmith seems to be interested. She gets out one of her famous notebooks, one for the latest Ripley book she’s working on, no less (maybe The Boy Who Followed Ripley, the next one to be published). She leans in, moves an ashtray across the table from between her and Nicholson so she can spread the book out for Nicholson to see; Highsmith scootches over to walk her interviewer through it like a kid showing off a school project.

The interview is fascinating because, in a way, it kind of works like a Highsmith story. The opening that lays out the scene, sets out some facts, routines, introduces characters who the reader may or may not be able to trust. And then there’s the moment when the wind changes direction. You see that the character who had shown little interest is actually the one in control, and the character who seemed personable is actually devious, troubled, unusual.

From talk of notebooks, Nicholson reveals her strategy, and we’re talking about Patricia Highsmith’s relationship with her father, with friends, with people. We don’t get to the core of anything too gritty, such as when Highsmith was young and she entered into conversion therapy to “cure” her of her lesbianism, and quickly set about seeing how many of her co-patients she could seduce. Her notebooks attest to many. The manuscript of Strangers on a Train is dedicated to “All the Virginias” acknowledging all the women named Virginia she’d slept with (the published version is changed to “Virginians”). But as the conversation gets more personal, the questions open up rooms with much more on display than simply how she lines up her pens. Nicholson, with a deft hand, reveals that Highsmith is more connected to her cruel, murderous, rational, amoral characters than she has ever been to a real human person. Nicholson draws a line between Highsmith and her most famous “psychopaths”, and she’s on to something. Highsmith cannot suppress an affectionate smile even at the very mention of Tom Ripley’s name, like she is being reminded of an old flame, or, more accurately, if you want to examine the twinkle in the eye above that smile, a current affair.

Patricia Highsmith’s life was a journey further and further into isolation; isolation from other people and from literary scenes. The tracks of that journey were littered with bodies not just of those murdered in the realms of her imagination, but of real world lovers she cast aside. Her copious diaries and notebooks detail these encounters, often luridly, and often without discretion as to who exactly she has left under the covers that morning. An arch seducer, and a ruthless jilter. Was her only real connection to her characters? She admits easily to Nicholson that she could not entertain the idea of living with someone, of having a relationship, a family, of having to indulge in the mundane conversations of the everyday. That would mean she wasn’t working if she was “like that”.

Nicholson has worked Highsmith brilliantly. All those box-ticking questions, and then snap! There is insight.

The publication of Highsmith’s diaries this year will reveal a woman in older age unconcerned with hiding her bigotry, her clear hatred of women, and her antisemitism. It’s almost as if the longer she wrote, the more morally wizened she became, like Highsmith was the portrait in the attic of her characters. Schenkar opens her biography with the epigraph: “She wasn’t nice. She was rarely polite. And no one who knew her well would have called her a generous woman”. It seems Highsmith’s Dostoevskian adventure made her more like Raskolnikov as she got older, and her characters mellowed out. She suggests to Mavis Nicholson that Ripley’s moral compass underwent a healthy realignment over the years. He now only tends to kill if he thinks somebody really deserves it. Highsmith appears very proud that Ripley has gotten this far, has been on that journey, has acquired himself a moral conscience. Nicholson asks Highsmith if she isolates herself on purpose. “Everything gets solved” in isolation, Highsmith says. For her characters, at least.

Gary Raymond is a novelist, critic, editor and broadcaster.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.