Peter Kennard is Britain’s foremost political artist and has been at the cutting edge of global political image making since the Vietnam War, a 45-year career of provocative, ground breaking and often harrowing art. As Unofficial War Artist, a year-long exhibition of his work, opens at the Imperial War Museum the artist provides Wales Arts Review with a personal and revealing insight into his work and relentless motivation.

‘A single death is a tragedy; a million deaths is a statistic’

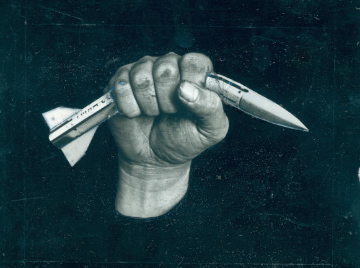

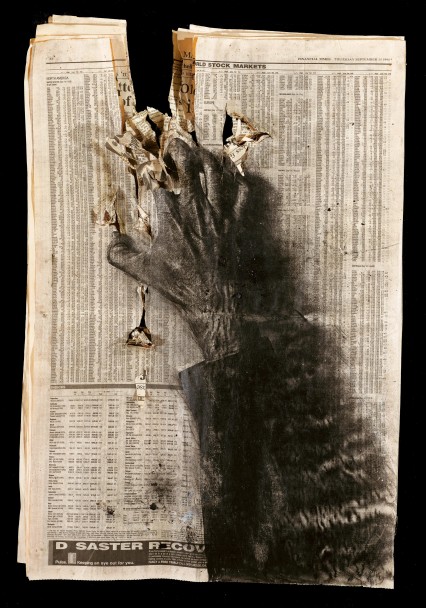

Three years after the invasion of Iraq, the medical journal The Lancet estimated that 654,965 Iraqi deaths had resulted from the invasion and occupation between 2003 and 2006, figures representing 2.5% of the population. There are no official figures from The Coalition who do not publicly account for either enemy or civilian deaths. Yet immediately behind the sliding doors of the Imperial War Museum’s latest exhibition sits a towering, foreboding and deathly montage representing the devastating human cost of Bush and Blair’s interminable folly, one that holds up a shattered mirror to the human condition in an attempt to force it to confront how ugly it is. Peter Kennard’s Decoration exits as a series of giant paintings that combine digital prints worked over in oil, a direct response to Iraq’s invasion by coalition forces. You can get up close to it, extremely close to it; it’s almost as if the artist is daring you to reach out and touch it, to make some kind of human connection. A flicker of democracy amidst the ashes of an utterly undemocratic conflict. This artistic inventory of atrophying military detritus seeks to brutally expose the eternally bankrupt bullshit charade of war existing as a byword for glory, the tattered ribbons and medal bars interspersed with images of faceless hooded captives and anonymous civilian suffering.

It consequently feels somewhat incompatible that the artist’s lifework should now form such a key component of a museum with a word as loaded as ‘imperial’ in its name. Sitting at the desk of his utilitarian Hackney studio Peter Kennard nods at this apparent paradox. ‘If it was down to me, I’d rebrand it as the People’s Peace Museum. The current name, though recently rebranded to IWM, can often put people off going there. They can easily assume that it’s a jingoistic yahoo kind of place, which it absolutely isn’t. They have a very large anti-war collection, they’ve been collecting for decades. The art isn’t in any way a glorification of war and the manner in which they now represent the Holocaust and the First World War is a great example of this.’

Having been politicised during the now iconic year of 1968, I ask the artist if he sees himself primarily as an activist who happens to be an artist or an artist who happens to be an activist. ‘I’ve never actually been asked that before,’ he smiles broadly, ‘but I’d say that my initial motivation was always art. I started being obsessed with making art at the age of 13 or 14 down in my parents’ coalhole at the bottom of the flats. I was very influenced by cubism, Bacon, and it only became informed by politics when I went to art school in the late sixties. 1968. It sounds like a bit of a cliché now, doesn’t it? But the big protests against the Vietnam War were happening at that time and I was very influenced by Don McCullin’s photography, pages and pages of it in The Sunday Times magazine section. That and Vietnam Inc. by the Welshman Philip Jones Griffiths, the greatest photography book there is about the Vietnam War. I asked myself whether my work was separate from my politics, and I felt that there was a way to join them together in some way. The whole hippy thing was happening at the same time too, which was so much more than a load of people dancing around in kaftans. I was squatting in Camden Town at the time in a completely hippy-fied street. Political bookshops were springing up selling political posters, and these were extremely influential and vital to that scene’.

Though war remains at the heart of Kennard’s work, the meaning of war is broadened to take in all manner of warfare committed against people by their elected representatives, the monetary as much as the military. ‘That’s a sort of given in the work. When I started it was Labour in power, Callaghan. Then Thatcher, and later Blair, and to me they’re all part of the same thing, they’re all attacking the workers, attacking the people, and my images are designed to expose what’s under the surface. That’s what photomontage is often about. I want to expose the ugliness. When Thatcher spoke about taking on Victorian values I created that image of her as Queen Victoria, looming imperiously. One takes on these ridiculous soundbites and then tries to turn it back on them.’ Does he feel that times of austerity – the 1980s, now – truly fulfil the received wisdom of inspiring great art? ‘They create a more combative, more down-home sort of art. By contrast, the 90s, the Damian Hirsts of this world, that era created art that was quite distanced from any form of social concern, and was often presented in quite an expensive way. I think that we’re now in a quite different time. Students seem much more interested in everyday materials, trying to communicate things that are really going on, because they’re truly experiencing it. Being made to pay massive tuition fees can only drive a political consciousness. Whereas the education system of the 1970s was fantastic in the sense that anyone, regardless of wealth, could aspire to attend the best educational establishments. That seems to be very much over now and it’s a tragedy, it really is.’

Kennard is an artist who has always taken the notion of ‘taking it to the streets’ literally, a little piece of him that will always be Paris ’68. ‘It’s such an important thing. People these days think that it’s enough to put things on the Internet, and that’s all very well but you have to find it, and it doesn’t have a physical presence. If you put things up on the street, on the walls of towns and cities, people are confronted by it, and they’re forced to engage with it properly. Younger artists are going back to doing things like this now, reclaiming private space.’

Indeed, Kennard’s work currently forms part of the Consumer poster project currently playing out across the streets of Cardiff, an evocative examination of the influence of consumerism on the visual landscape. In partnership with his former student Dawn Woolley, Consumer uses traditional advertising space as a means of showcasing artwork that critique consumerism and capitalism, each employing methods of enticement that are often found in adverts, a means of encouraging people to think about the contradictions of capitalist consumption rather than compel them to buy something.

In a similar vein fellow artistic provocateur Banksy, the embodiment of contemporary provocative street art – has spoken at length about how much Kennard’s work has influenced him – ‘I take my hat off to you, Sir’ –and I ask Kennard how he feels about the wide scale attempts to commodify Banksy’s work. ‘As we know,’ he laughs, ‘capitalism can commodify most things. It’s what we used to call in the 70s “repressive tolerance”. There’s a whole thing about Banksy’s work being bought up by collectors for a small fortune, but he does actually do very good things with his money. He does help other artists; he’s helped groups in Russia; he financed a whole group of us to go out to Palestine and do work out there on the apartheid wall. His show there raised a lot of money because of his prints and all of the money stayed in Palestine to be used by students and artists. There’s clearly a huge desire to own his work by wealthy collectors but it’s not something he actively encourages or approves of.’

The Weimar-era Nazi-baiting photomontage work of John Heartfield was a significant early influence upon Kennard and one that first crossed the radar of this writer via the sleeve of Siouxsie and the Banshees’ Metal Postcard (Mittageisen). ‘I was inspired not just by the work itself,’ Kennard explains, ‘but how Heartfield got it out there, on magazine and books covers and posters. The production of the work became part of the work itself and that was a big influence upon me in the late 60s when it was exhibited in London. Looking at Dadaism, looking at the 1930s, that period when artists and writers worked hand in hand in the fight against fascism. Heartfield, Brecht, that whole group of people working under a culture of danger and constant intimidation. Heartfield was eventually put on a state sanctioned hit-list and he ended up in Britain where of course they didn’t really understand him. All of these amazing artists came over here, the likes of Kurt Schwitters. Except they didn’t understand his collages in England so he painted portraits to make money and there was a wonderful letter in the Tate’s exhibition of his work that he’d sent to André Breton in which he said “…and I came second in the painting competition. To Mrs Jones.” Brilliant!’

Gazing at the walls of Peter Kennard’s studio, with its unsettling images of weaponry and nuclear destruction, I’m instantly transported back to being the Cold War kid whose callow teenage skin I’ll almost certainly never succeed in fully shedding. Especially given the fact that the all-pervading menace of global nuclear destruction has never truly receded.

‘It’s as if that threat has somehow gone away,’ Kennard says. ‘It’s one of the things about our culture and our media. The way in which they can define what the agenda is, when the agenda is not to think about nuclear weapons at a time when this country is about to spend about £100 million on recommissioning Trident at the expense of health and the alleviation of poverty. I still think it’s a totally crucial issue. They’re making smaller weapons now, battlefield weapons, the kind of things they actively considered using in Iraq, and the cost of this madness just goes up and up an up.’ It’s a theme that Kennard uses to hugely impactful effect within the framework of Unofficial War Artist, the juxtaposition of his photomontages with numbers to form a living audit of war in terms of both the human and financial cost – a list of countless zeros which, he says, form the noose with which we are slowly killing ourselves and each other. Yet these noughts can also exist as links in a chain, or as Kennard describes it, ‘a chain of protestors and resistors refusing to accept the nightmarish calculus we are endlessly told is inevitable.’

For anyone who is aware of Kennard’s now iconic Haywain with Cruise Missiles – the jarring insertion of three nuclear warheads into the idyllic East Anglian countryside traditionally depicted by John Constable – it is particularly inspiring to hear of how Kennard recently reinvigorated his work in an actively dynamic manner via a live protest against the National Gallery’s acceptance of sponsorship from the arms group Finmeccanica: ‘That was part of a campaign against the entire arms trade and it was discovered that Finmeccanica, the fifth biggest arms manufacturer in the world, was not just sponsoring The National Gallery but hosting dinners for arms dealers there during the global arms fair. On the day of one of these dinners a lot of people went to demonstrate and I stood in front of the actual Haywain holding my Haywain with the nuclear missiles on it. We got moved on of course, but about three months later The National Gallery pulled the sponsorship so it’s fair to say that all of the negative publicity we created actually worked.’ He leans forward and laughs: ‘Something worked! People tell me I’ve spent the last 50 years protesting and nothing’s actually worked. Well, things do work occasionally. Small victories perhaps, but important victories nonetheless.’

Peter Kennard’s staggering work is often beautiful and ugly in equal measures, yet it is nothing if not forged in the redemptive flames of hope. Sipping from a mug of thick black coffee he sits back in his chair and reflects back upon the turbulent period when he first started working with CND: ‘There were people there who didn’t want to show the horror, they wanted to show rainbows and people gambolling around in the countryside, and I thought that that was truly pessimistic, the depiction of an utterly unreal future. It’s much more optimistic to try and portray what’s actually going on in the world because by portraying it there’s always that chance that you can ultimately break through to something different, something better. A point at which people can invent their own utopias. As Bertolt Brecht once famously said, “Don’t start from the good old things but the bad new ones.”’

Peter Kennard’s staggering work is often beautiful and ugly in equal measures, yet it is nothing if not forged in the redemptive flames of hope. Sipping from a mug of thick black coffee he sits back in his chair and reflects back upon the turbulent period when he first started working with CND: ‘There were people there who didn’t want to show the horror, they wanted to show rainbows and people gambolling around in the countryside, and I thought that that was truly pessimistic, the depiction of an utterly unreal future. It’s much more optimistic to try and portray what’s actually going on in the world because by portraying it there’s always that chance that you can ultimately break through to something different, something better. A point at which people can invent their own utopias. As Bertolt Brecht once famously said, “Don’t start from the good old things but the bad new ones.”’

Or as the dramatist Harold Pinter once remarked: ‘Kennard sees the skull beneath the skin all right’.

All artwork appears courtesy of the artist and with the valued assistance of the Imperial War Museum.

Studio photographs by Craig Austin.