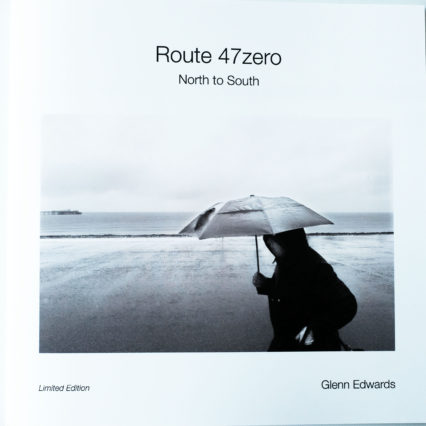

Ben Woolhead talks to photographer Glenn Edwards about his new exhibition in Colwyn Bay, and the accompanying zine marking his work along the A470, and the lasting influence of his mentor, David Hurn.

Call it hiraeth if you like. In the late 1960s, after more than a decade shooting everything from the Hungarian Revolution to London at the height of the Swinging Sixties, via behind-the-scenes assignments on From Russia with Love and Barbarella, photographer David Hurn felt a compulsion to return to Wales and devote himself to capturing the country of his youth (if not actually his birth). Some 50 years later, Glenn Edwards – a former UK Press Photographer of the Year who counts himself ‘lucky enough’ to have attended ‘the world-renowned Documentary Photography course in Newport’ which was led by Hurn – experienced the exact same lure. Hurn’s travels the length and breadth of the country culminated in the publication of Wales: Land of My Father in 2000; Edwards’ own peregrinations have now borne fruit in the form of both an exhibition and a self-published zine.

‘Peregrinations’ is the right word, because Edwards took as his subject the A470, the road that takes its time meandering from north to south. ‘For the past 20 and more years, I’ve worked around the world, predominately in Africa, and not really looked at my own country for a long-term project, and I wanted to find a theme,’ he explains. ‘I found an article in the Western Mail saying there was a move to rename the road the Royal Welsh Way. The road travels from Cardiff all the way through town and city, rural and urban, to Llandudno on the northern coast and it seemed a perfect catalyst.’

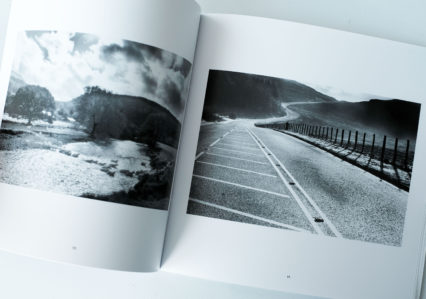

Route 66 in the US has been much mythologised and documentary photographers Jon Nicholson and Peter Dench have followed in the footsteps (or, rather, tyre tracks) of Paul Graham in focusing their lenses on the A1, the original tarmac backbone of Britain. Its Welsh equivalent has, by contrast, been largely neglected. Some would claim rightly so. Ian Parri, for instance, is the author of Nid Yr 470, a light-hearted Welsh-language travel book which plots a route from the north coast to the capital that bypasses what he’s branded ‘this incredibly dull and tedious road’. Others, however, would disagree. A 2001 photographic exhibition at the Oriel Mostyn in Llandudno prompted BBC Wales’ Jon Gower to lyrical eulogy: ‘From the rugged grandeur of Snowdonia, through the quiet music of mid Wales’ landscape and on to the populous south, this is the Welsh highway.’ Asked to name his favourite stretch of the A470, Edwards puts himself firmly in Gower’s camp rather than Parri’s: ‘The road is so varied in landscape and I don’t think we realise how lucky we are in Wales to live in such an incredible country. I love the rolling hills, I love the harshness of Snowdonia, so I will just pick the section after Rhayader to Llangurig simply because when it’s quiet it’s brilliant to put your foot down and forget about photography for a few miles.’

In truth, Gower’s term ‘highway’ is perhaps a little misleading. As he himself admitted, the A470 is ‘more of a proceed-at-your-leisure, B road sort of A road’. Its single-carriageway stretches mean that you’re often more likely to find yourself pootling along behind a caravan or a tractor than able to ‘put your foot down’ – which appears to be Parri’s main complaint. Yet the fact that your arrival time always seems to be now-in-a-minute (to use a fine Welsh expression) means that travelling on the A470 becomes more about the journey than the destination and practically guarantees that you’ll make serendipitous discoveries along the way. Which, naturally, makes it the perfect subject matter for a photographer.

In truth, Gower’s term ‘highway’ is perhaps a little misleading. As he himself admitted, the A470 is ‘more of a proceed-at-your-leisure, B road sort of A road’. Its single-carriageway stretches mean that you’re often more likely to find yourself pootling along behind a caravan or a tractor than able to ‘put your foot down’ – which appears to be Parri’s main complaint. Yet the fact that your arrival time always seems to be now-in-a-minute (to use a fine Welsh expression) means that travelling on the A470 becomes more about the journey than the destination and practically guarantees that you’ll make serendipitous discoveries along the way. Which, naturally, makes it the perfect subject matter for a photographer.

As someone used to undertaking commissions, Edwards relished the creative freedom he had for Route 47zero: ‘I always feel that with it being a self-initiated project there was no deadline other than self-imposed, so more time could be spent on specific situations. I could also pick what those situations were. I didn’t have a storyline given to me by a client that I had to follow, so I could follow my own interests and then edit my own work for my own pleasure.’ Not that there weren’t metaphorical caravans and tractors along the road, however.

Talking about his own project on the A1, Peter Dench has said: ‘One of the hardest things as a photographer is to keep swinging your legs out of bed, leaving loved ones behind to spend money you might not have for no determinable financial reward.’ It’s a predicament with which Edwards is all too familiar: ‘Driving up and down the road can become expensive to the point that I had to give it a break – it was just costing too much. I knew I hadn’t finished the project and there was more to take, but what was I going to do with it?’

Thankfully, an opportune invitation to exhibit the project at this year’s Lorient Celtic Festival in Brittany gave him ‘the kick required’, and it subsequently helped the Welsh Pavilion draw in record crowds. Leafing through the zine, it’s not hard to see why.

Many of the black-and-white images endorse Edwards’ observation about the rich variety of different landscapes through which the A470 curves, climbs and descends. The road routinely affords those who travel along it spectacular vistas and stunning scenery. Parri’s description appears all the more perverse; if any road is ‘incredibly dull and tedious’, it’s the more photographically feted A1 – a flat, monotonous artery offering views of little more than rubbish-strewn verges, grubby truckers’ caffs that time forgot and former Little Chefs converted into sex shops.

However, as befits someone who is a documentary rather than a landscape photographer by trade, Edwards is ultimately more preoccupied with people than with the natural environment, and often with the relatively mundane than with the extraordinary. In this respect, his admiration for the ‘gentle style’ of his former mentor David Hurn’s work is unsurprising: ‘It is what I feel documentary photography is about: photographing the normal in such a beautiful, compelling way to give a glimpse of our world now and be of interest in 100 years and more.’ The images in Hurn’s Wales: Land of My Father trace the processes of economic, social and cultural change over a period of decades, and its influence on Edwards’ project is obvious. ‘Living in the city,’ he points out, ‘it’s easy to lose sight of the country we were born in and the traditions that are within. Travelling the A470, you visit all aspects of Wales and it can be an eye-opener when seeing parts that seem as if they have been left behind, especially the farming community.’ In this respect, you can’t read the photo of a flat-capped man stood stoically on the verge attempting to hitch a ride, his sheepdog lying patiently at his feet, as anything other than symbolic.

However, as befits someone who is a documentary rather than a landscape photographer by trade, Edwards is ultimately more preoccupied with people than with the natural environment, and often with the relatively mundane than with the extraordinary. In this respect, his admiration for the ‘gentle style’ of his former mentor David Hurn’s work is unsurprising: ‘It is what I feel documentary photography is about: photographing the normal in such a beautiful, compelling way to give a glimpse of our world now and be of interest in 100 years and more.’ The images in Hurn’s Wales: Land of My Father trace the processes of economic, social and cultural change over a period of decades, and its influence on Edwards’ project is obvious. ‘Living in the city,’ he points out, ‘it’s easy to lose sight of the country we were born in and the traditions that are within. Travelling the A470, you visit all aspects of Wales and it can be an eye-opener when seeing parts that seem as if they have been left behind, especially the farming community.’ In this respect, you can’t read the photo of a flat-capped man stood stoically on the verge attempting to hitch a ride, his sheepdog lying patiently at his feet, as anything other than symbolic.

‘One of my favourites was taken at the Erwood Show of youngsters having their sheep judged,’ Edwards says. ‘I just feel these animals were probably more pet than business and I can imagine the work these kids put in to make sure the sheep were looking their best. I like the concentration on the running boy and the white coat that doesn’t quite fit. I wonder what the Erwood Show will look like in 100 years – maybe exactly the same.’ The superb photo on the facing page, taken at the Royal Welsh Show, looks like a tableau: in the centre, surrounded by cattle, a young woman who could be a model straight out of one of Hurn’s Swinging Sixties shots lies sleeping, while to the side a lad sits, hunched, teasing a piece of straw between his fingers – maybe glumly, maybe anxiously, maybe distractedly, maybe out of boredom.

While the composition of that individual shot may have been a happy accident (Edwards admits that an element of luck was involved in capturing some moments), the pairing certainly isn’t. Considerable care was taken with the zine’s layout.

While the composition of that individual shot may have been a happy accident (Edwards admits that an element of luck was involved in capturing some moments), the pairing certainly isn’t. Considerable care was taken with the zine’s layout.

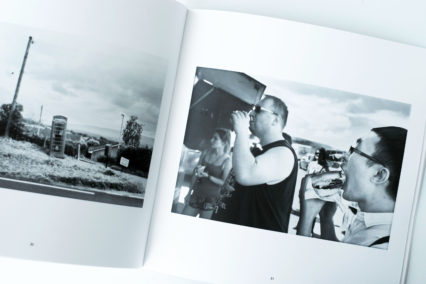

‘I like pictures to tell stories,’ he says, ‘and if by putting images together they add to the narrative, it’s important to me.’ Hence the opening photo of ramblers in Libanus filing past a red phone box (a visual motif that recurs throughout, signifying historical change) and into the zine, facing an image of a lone Dalek trundling along in Cardiff Bay. Hence why a shot of a couple perched on roadside deckchairs looking at the red kites of Rhayader is paired with another of spectators at a harness-racing event – like Martin Parr and others, Edwards frequently watches the watchers, foregrounding the act of observation so central to his art. Hence the way the final two images – of French rugby fans in fancy dress outside Cardiff pub the Goat Major and of cyclists enjoying the seafront promenade in Llandudno – serve as a reminder of where the A470 starts and ends, and of the journey on which the photos have taken us.

The limited-edition zine is close to selling out, but many of the images will be exhibited at the Northern Eye Photography Festival in Colwyn Bay in October before moving to the Andrew Buchan pub on Cardiff’s Albany Road from the beginning of November. ‘I thought I would put it somewhere different from the galleries to show a different audience,’ Edwards explains. ‘The pub is known for showing exhibitions and this will take three-quarters of the space so it will have a good show.’ And after that? While he says he’s ‘very happy and contented’ with the project as it currently stands, it’s ‘not totally finished’: ‘I felt I had come to a convenient end to part one.’ Here’s to part two, then.

Images from the Route A47zero project will be on display from 7th to 20th October 2019 as part of the Northern Eye Photography Festival in Colwyn Bay.