St David’s Hall, Cardiff, 4 October 2013

Francis Poulenc – Gloria

Dmitry Shostakovich – Symphony No. 8

Soprano: Marita Sølberg

Conductor: Thomas Søndergård

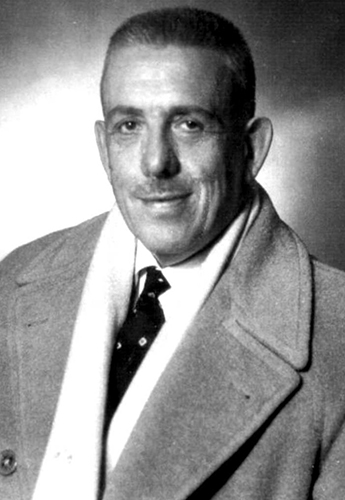

This year sees the fiftieth anniversary of the death of Francis Poulenc, who collapsed suddenly with a heart attack on 30th January 1963. Henri Dutilleux – who himself died earlier this year – purportedly once described his elder compatriot as ‘a point of reference’, adding that ‘in this capacity, France needed a musician like him following Chabrier, whom he adored.’ Certainly, Poulenc is the best known and most accomplished composer of his erstwhile fellows in the Groupe des Six of the 1920s; a loose association of chic enfants terrible*, who were guided by Eric Satie and who often found themselves hanging onto the coat-tails of the (in)famous Igor Stravinsky. In his lifetime, Poulenc grew resigned to his place as a minor composer in comparison to such figures as the iconic, colourful Russian who, by the ‘20s, was largely based in France. Poulenc himself was often seen as ‘colourful’ – although, in his case, the epithet more often took the form of disparagement as a lightweight prankster, based on the urbane, witty and apparently flippant music of his earlier years. In truth, people were often challenged by his seemingly opposing positions – not least as an openly homosexual bon viveur who drew ever more devoutly towards his Catholic faith following the shocking death of a lover in a car accident in 1936. In the latter part of his life, Poulenc composed many pieces for the church but his style remained essentially light-hearted and neo-classically refined; freshly original but based on such ‘old-fashioned’ cornerstones as a fluent melodicism and simple tonal harmony with a dissonant bite. As he himself once said, ‘I am a musician without a label.’ But this has hardly prevented audiences from appreciating his music, as they did enormously tonight at St David’s Hall, in a sprightly and touching performance of the Gloria by the combined BBC National Orchestra and Chorus of Wales, together with soprano soloist Marita Sølberg, under Principal Conductor Thomas Søndergård.

It turned out to be a night of anniversaries, and no doubt Poulenc would have loved the spontaneous rendition of ‘Happy Birthday’ which greeted a happily surprised Søndergård from an audience already won over by his easy rapport and impressive first year at the helm. Not only that, but tonight was the 30th anniversary to the day of the first ever rehearsal of the Chorus – and their first ever concert with Søndergård to boot. Characteristically open and generous regarding other composers – however different from himself – Poulenc may also have appreciated being paired with Shostakovich on this occasion; a Russian who – in his intensely grief-laden Symphony No 8 at least – represents an entirely contrasting figure to the man famously described as ‘half monk, half delinquent’ by the critic and musicologist Claude Rostand.

Poulenc’s Gloria was written a year or so before his death and is an intriguing example of his idiosyncratic marriage of sincere religious feeling with sheer, tongue-poking delight at life (quite literally, as it was in part inspired by frescoes of angels doing just that). Søndergård’s reading of the work looked set to take its cue from the latter cheekiness as, after a dignified introduction, the conductor took off at pace with the first entry of the Chorus. However, things settled by the ensuing Laudamus te and, from then on, clipped, bouncing accents were nicely balanced by a poignant tenderness – albeit at times lacking the broad phrasing that would have allowed the Chorus to shine completely in the hall’s acoustic (no doubt this did not affect the radio broadcast). But overall, the performance was one of great sensitivity and incision, aided by the stunning clarity and rich, creamy tone of Marita Sølberg, whose faultless pitching and top register gave the performance exquisite focus. Her Domine Deus – in both third and fifth movements – and the final ‘Amen’ were mesmerising.

*

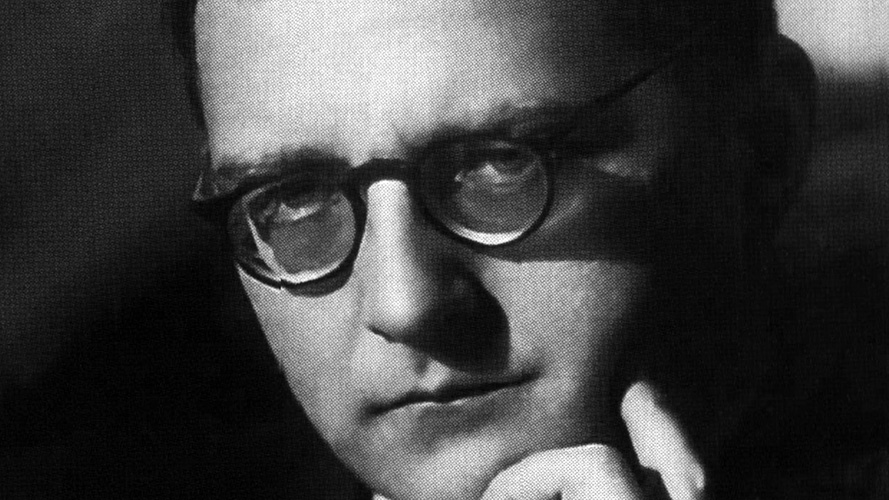

If Poulenc represented the ‘point of reference’ for French music, it is Shostakovich who has become the musical byword – in the Western popular imagination at least – for endurance in wartime and artistic resistance to totalitarian oppression. Inevitably, in a history so fraught with propaganda on all sides, there remain many contentious issues surrounding Shostakovich’s role in Soviet Russia and the extent to which he may or may not have been a dissident. Arguments over the authenticity of certain texts published under his name (like his largely discredited memoirs, Testimony) represent only a fraction of the battles still being fought over him by scholars.** All of this adds further levels of irony to the utterly devastated and devastating music Shostakovich composed ‘about’, or inspired by, war – of which his Eighth Symphony is a stupendous example. Whether the music can be said to be ‘about’ Hitler or ‘about’ Stalin; whether it is ‘about’ the terrible pogroms against Jews and dissenters pre-Second World War*** – or whether it is simply Shostakovich’s own personal response to horror, loss and trauma – is ultimately unknowable. But it is highly unlikely that listeners who have even the least knowledge of Shostakovich’s biography or the symphony’s background can truly put all that aside and do what Gerard McBurney pleaded for in tonight’s programme note, which was to focus on the music alone, without such external baggage of interpretation. Nor would that necessarily be ideal – albeit that notes in themselves are of course neither ‘political’, nor ‘emotional’. What we can do, perhaps, is choose to listen consciously; aware of the paradox that, on the one hand, all musical expression is on some level a political act (including Poulenc’s) and that, on the other hand, Shostakovich today is, in many ways, still as subject to interpretation, polemic and revisionism as the historic tool of propaganda he fought not to become.

Unlike the previous, more belligerent ‘Leningrad’ Symphony (1941, more usable as propaganda therefore more acceptable to the authorities), the emotional tenor of the Eighth is the unrelenting ‘pity’ of war, to echo Wilfrid Owen. Composed in 1943, in the midst of a long and terrible conflict which can barely be imagined, it is a threnody, if you will, for humankind – and it appears surprisingly rarely on concert programmes compared to other Shostakovich symphonies. In tonight’s hugely convincing performance, Søndergård drew out the agony with some slow tempi but without tipping into the maudlin. The rich strings of the BBC NOW were key to prolonging the tension, with a long-range dynamic understanding built right from the start, as extended, thematic line after line was taken up and morphed by brass and woodwind into melodies of, at times, unbearable anguish. The opening Adagio – Allegro non troppo, of course, features the cor anglais solo most often associated with just that emotional extreme and here, Sarah-Jayne Pormoguer played it with immense empathy and pathos.

Indeed, this symphony relies as much on the emotional stamina of the many soloists from each section as their musical ability, and the playing tonight was as magnificent as we have come to expect from a BBC NOW which is growing ever more in stature. Plaudits are due to all, but Eva Stewart was outstanding (I never thought I would find a Shostakovich piccolo part ‘soulful’), as was principal trumpet Phillippe Schartz – particularly in the third movement – with oboist David Cowley in the fourth… the list simply goes on.

Any orchestral performance stands or falls by its teamwork, however, and particularly so in a symphony of this monumental scope. And BBC NOW are, quite clearly, a team. Shostakovich’s Eighth has an unusual, five-movement structure and is sometimes apt to feel like a series of gaunt climaxes – complete with brutal outbursts, marching marionettes and titanic major-minor clashes – interspersed by great, dark stretches of no-mans-land, interminable in length (however appropriately so). But Søndergård was able to rely on the collective sensitivity of his players to intuit his direction, allowing shapes to coalesce and disperse with some fine dovetailing of phrases back and forth between sections of the orchestra – and, indeed, from section to section of the work. This was true of each movement, but was most hard-won tonight in the final fourth and fifth; parts of which can drag cruelly, but which Søndergård managed to steer with great poise on the right side of bleak isolation.

Cadences are, to my mind, unusually crucial in this work, serving as points of departure as well as arrival – and they are vital moments of tension release in Shostakovich’s rolling, crushing orchestral machine. Perhaps Søndergård expressed it most succinctly in his post-concert Q and A, when he spoke of needing to ‘find the meaning of the sentence’ in the piece. On many levels, ‘finding the meaning’ of this work is a loaded concept for the reasons I’ve discussed. But navigating securely from cadence to cadence – as it were from sentence to sentence – and, within those, slipping adroitly from key to key, seems to determine the success or otherwise of its overall shaping from a grim C minor to an eventual C major just as harrowing. Perhaps it is not too outlandish to suggest that composing these harmonic and melodic ‘sentences’ into a symphonic form so quickly – in just forty days or so – is part of what enabled Shostakovich not merely to stay sane, but to express in such plain terms, a profound universal humanity in the midst of such unending destruction and despair.

* including Darius Milhaud, Georges Auric, Arthur Honegger, Louis Durey and – trailblazing as a woman – Germaine Tailleferre.

** to the extent that a book, pointedly entitled The Shostakovich Wars (by Allan B. Ho and Dmitry Feofanov) was published in 2011 to counter the hitherto allegedly ‘definitive’ text on the subject, Malcolm Hamrick Brown’s A Shostakovich Casebook (pub. 2004).

*** From Testimony – ‘the war brought much new sorrow and much new destruction, but I haven’t forgotten the terrible pre-war years. That is what all of my symphonies, beginning with the Fourth, are about, including the Seventh and Eighth.’