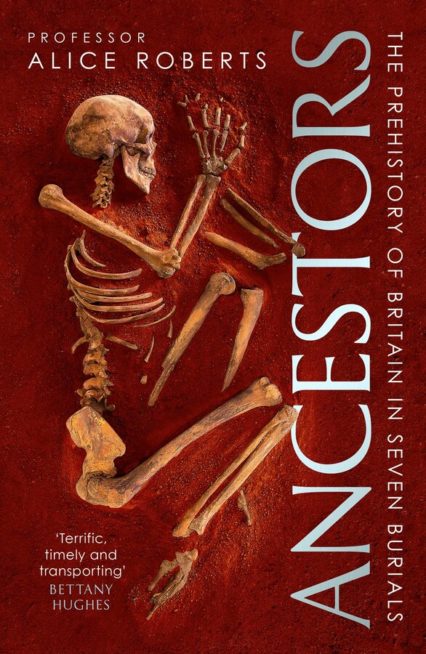

Following the release of her book, Ancestors: A prehistory of Britain in seven burials, Caragh Medlicott caught up with Professor Alice Roberts to discuss what we can learn about ourselves by looking to the past, and why art and storytelling have always been fundamental to human culture.

Caragh Medlicott: I’d like to start by talking about the link between biology and archaeology. I think to a layperson, they aren’t necessarily two things that are inherently connected – but that relationship is very integral to your work, isn’t it?

Professor Alice Roberts: It is. I’m really interested in this intersection between biology and history. I’m a biological anthropologist, myself, and that means that I look at humans from a biological perspective – but at the same time, you can’t help also being fascinated by the cultural context, too. My book, Ancestors, is about burial archaeology. It’s looking at the prehistory of Britain through a series of burials – and those burials form the framework of the book. Really, a burial represents the meeting point between biology and archaeology because it’s essentially a time capsule. I can look at the bones found there and extract information from them – I can tell lots about that individual such as how old they were when they died, how old the skeleton is, and what sex that person was. I can also start to look for evidence of disease, too.

So, what you’ve got is something like a physical biography written into the bones along with a whole range of artefacts that are placed in the grave, too. These can also give us an astonishing insight into the culture of the time, seeing things like the kind of clothes they would have worn and the kind of objects they would have used in their day-to-day life. It’s through these things that we also see something about the humanity of people in past societies – how they were so careful in the treatment of their dead, the way they included a careful selection of artefacts to put in the grave, too. So, I think we learn a lot more about the past by bridging biology and archaeology and culture together. And we can also learn something about ourselves, as well.

Caragh Medlicott: Your book, Ancestors, is told through the exploration of seven different burial sites. I wondered when writing the book how important storytelling was in translating the information into something accessible?

Professor Alice Roberts: Well, I think storytelling is how we understand the world. And as a species we’re very, very good at storytelling. It’s how we make sense of our environment, and it’s also how we pass on information from one person to another. As I was writing this book, I was delighted to be digging into the research literature and finding so many amazing stories. So, the selection of burials in the book was really driven by how good a story they could tell. That narrative was really important to me when I was writing – and I think for all of us as humans, storytelling is fundamentally important.

Caragh Medlicott: I suppose people tend to think of science as very precise and factual, which of course it is, but when making sense of findings, imagination must play an incredibly important role, too.

Professor Alice Roberts: I think a lot of the time we tend to focus solely on the outputs of science. We come to it after scientists have gone through the whole process of sorting through different hypotheses and getting rid of the ones that don’t stack up to the evidence until we’re left with the final answer. But what’s really interesting is the whole process, there’s a huge place for imagination and creativity in science. When we reduce science to just its conclusions we’re really missing out on the exciting bits, I think we miss out on the actual excitement of discovery and the imagination that is required to interpret these discoveries.

You know, you find an object in somebody’s grave and your imagination fires up – you start thinking about what that object could have possibly been or meant. It’s important not to leap to just one conclusion, but to consider all the different possibilities thoroughly. That’s where imagination is crucial. That’s why I get dismayed when people say that science isn’t a creative subject. It’s incredibly creative, especially in that phase where you’re looking to generate interpretations which you can whittle down until you start to close in on the truth.

Caragh Medlicott: One of the things that you highlight in your book is that sense of connection with the deep past, the bridge between these two moments in history with the original burial and the excavation. How does it feel to hold a human skull from thousands of years ago? Does it still feel profound, or are you used to it by now?

Professor Alice Roberts: It always feels profound. Every time you do it, and especially when you’re excavating and you come across an object in a grave, there’s always that feeling of connection. It’s those moments through time, as you say, the thread between finding the object and then the last time it was looked at or held in a human hand – which may be hundreds, if not thousands of years ago. And that does feel like a really strong, visceral connection. That’s what I love about archaeology and physical history, the fact you can hold something in your hand. It’s incredible.

Caragh Medlicott: And you actually started your career in the medical field as a doctor, how did you end up moving more towards history and archaeology?

Professor Alice Roberts: I did. I studied medicine at Cardiff University. And I practised as a junior doctor in the Heath hospital and in the Prince of Wales hospital in Bridgend. Then I did what I thought was going to be just a six-month job, teaching anatomy to medical students at Bristol University – I was still doing some surgery as well during that post. But I always loved anatomy, the actual structure of the human body, which obviously is quite fundamental to medicine. And I love teaching, too. I started doing some research on old bones which is where that fascination really took off. I was offered an extension on that post and ended up staying at Bristol University for eleven years. So, I took a sidestep from medicine into academia, and haven’t looked back since.

Caragh Medlicott: I assume that’s not a typical route.

Professor Alice Roberts: Well, you say that, but actually, there are quite a lot of people who were originally medical that end up working in biological anthropology – and working with archaeologists in that way. So, it’s not a completely atypical route to biological anthropology.

Caragh Medlicott: I wonder, given the current political climate and deepening divisions, if you think that looking to our ancestors could actually be quite helpful in giving us a sense of shared belonging and history?

Professor Alice Roberts: I think it definitely can. Part of what I write about in the book is a connection to landscapes through time, thinking about all the people that have walked in these places before us. And you don’t need to have a direct genetic or family relation with these people for it to be meaningful. I mean, I feel this relationship to the land very powerfully when I’m walking in the British landscape, there’re so many examples of the past that that are there in the landscape – you almost feel the ghostly presence of our ancestors. But I think you can enjoy that without feeling that you have to own the landscape or indeed those ancestors. I think they belong to everybody.

Caragh Medlicott: A lot of your work focuses on tracking the mass migration of early humans and the resilience they displayed in reaching every corner of the earth. Do you think we’ve maybe given stone age people an undeserved reputation with this joke in pop culture that cavemen were stupid?

Professor Alice Roberts: Yes, they certainly weren’t knuckle draggers. I think people who were living in the stone age were very much like us. They didn’t have the technology we have today, and the culture was different, but they still approached the world in a similar way we do. They were trying to work out how to survive, subsist – they were problem solving on a daily basis. I also think they were interested in art – we see that going way back into prehistory, a real fascination with artistic expression, and also with decorating yourself. We don’t get many clothes preserved from the past, though sometimes we get amazing mummies with persevered clothing, of course. But even when we don’t have the soft, organic parts of people’s clothes we still might have little clues in the fixings and fastenings so that we can tell that people actually paid quite a lot of attention to their appearance. You know, they weren’t just wandering around in a rough bit of fur. They were actually wearing properly tailored clothes going a long way back, tens of thousands of years ago. There are some fantastic examples of burials where we’ve got really good representations of clothes. For instance, the fantastic iceman Ötzi, from the Alps, where we see what a bronze age person would have been wearing. And actually, his clothes were quite chic!

A prehistory of Britain in seven burials by Professor Alice Roberts

Caragh Medlicott: On the topic of art, I wonder what you’ve learned about the importance of art to human cultures around the world and through the ages?

Professor Alice Roberts: Art goes back a really long way. We’ve even got evidence of some form of artistic expression going back about half a million years– there was a shell that was discovered in Java which had zigzags engraved into it. The original excavations found a specimen of Homo Erectus – the “Java man” – so not even our own species, but a pre-existing one. You just look at that shell and say, no other animals do anything like this. It seems to be a real human drive and it goes back a very, very long way.

I also think we sometimes overlook the importance of art, it’s sometimes viewed as a bit of decoration, a bit of frippery, something that’s not quite as serious or important as other aspects of our culture and advancing technologies, the things that are important to our survival. But I think art is part of our survival, both now and in the past. It’s a really important way of communicating – and we see that very clearly when we look at past societies.

Caragh Medlicott: So, it’s not too romantic to say that it is part of what makes us human? That it’s about meaning, something we do that doesn’t have explicit utility.

Professor Alice Roberts: I do think it is part of what makes us human, but I do also think there’s utility to it. And that’s because I think it’s a really profound means of communication – because art means expressing something while also communicating something at the same time. So, I think it’s incredibly important from that perspective, too. And – I may be going out on a limb here – but it may be as important as spoken language. Visual language has been incredibly important to human societies.

Caragh Medlicott: What’s something you think we can learn from early humans and past societies?

Professor Alice Roberts: When we look back at past societies, we see our ancestors surviving through really difficult periods of time and facing many challenges. We see that they cooperate to meet these challenges and are able to survive, actually, against the odds. There were several times in human prehistory where our species could easily have disappeared from the face of the earth, but we clung on because of the way we work together. I think that’s a really powerful message for us today.

The other message from the past, I think, is that nothing stays the same. That’s particularly true if we look at Britain through time, what we see is many different groups of people arriving at different times throughout prehistory, and obviously it’s history as well. Each of these groups of people bring different ideas and different cultures which will enrich what was already there beforehand. So there’s that sense of ongoing change, and the ongoing arrival of people into places as well that I think helps us to make sense of our current situation, too. We might sometimes live under the illusion that things are quite static, but if we look back over a few decades – or maybe a century – to take the longer view, we see that things have always been dynamic in human societies, and there have always been migrants arriving in Britain.

Caragh Medlicott: And what’s next for you?

Professor Alice Roberts: I’m touring with the book at the moment, which is fantastic, it’s brilliant to be back in front of live audiences again. This is my first tour since the beginning of the pandemic so it’s just wonderful to see people and engage in a room. It’s so much better than giving a talk over Zoom.

I’m also finishing up a brand-new series of Digging for Britain which is coming back to the BBC, and actually we’re back on BBC Two this year. So hopefully that’ll either be this year, just before Christmas, or possibly going into the new year. We look at a fantastic range of archaeology and the show is really about documenting the archaeology as it happens. I’ve been spending quite a lot of the year travelling around the country visiting lots of different archaeological sites and seeing those discoveries as they emerge – it’s been very exciting.

Ancestors by Professor Alice Roberts is available now. You can also see Professor Roberts speak in Cardiff at St David’s Hall on 10th November. Tickets are available here.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.