‘Criticism’ has become a very difficult word, because although its predominant general sense is of fault-finding, it has an underlying sense of judgement and a very confusing specialised sense in relation to art and literature, which depends on assumptions that may now be breaking down.

Raymond Williams, Keywords, 1976

This writer’s last visit to Tate Liverpool was for the suitably sequined ’70s spectacular, ‘Glam! The Performance of Style’, and although only a year has elapsed, since then the gallery has opted to leap forward a decade. Though this exhibition spans a period from the first publication of the book upon which it is loosely based to the last year of Tory rule in 1996, it nevertheless retains a core focus upon the more challenging elements of the British art scene of the 1980s; a confrontational and politically combative period underpinned by a number of the keywords contained within the author’s original text: ‘Violence’, ‘Liberation’, ‘Alienation’ and ‘Class’.

First published in 1976, Keywords, the work of the Welsh academic and writer Raymond Williams, has become a seminal text in the study of the English language. It is a searching inquiry into the changing meanings of 131 keywords positioned as essential to an understanding of both culture and society. A highly influential figure within the New Left, Raymond Williams will undoubtedly have felt some sense of kinship with this ambitious and sprawling interpretation of his work, inspired as it is by the consistent themes of radicalism and defiance, its manifestation of words from his book confronting the viewer at sporadic intervals and grouping the works in relationship to a specify key word.

Haywain with Cruise Missiles 1980

Chromolithograph on paper and photographs on paper

260 x 375 mm

© Peter Kennard. Image courtesy Tate

‘Who do you believe in?’ asks a disembodied voice to a procession of ’80s youth, a series of scenes from Dick Jewell’s film Headcases. ‘Myself,’ respond the majority, a consistency of response rivalled only by ‘nothing’. It’s a simple sequence of exchanges but one that says much about the 1980s itself, a decade that shamelessly embraced self-regard and alienation in equal measures. It was a decade undoubtedly riven with confrontation (the miners’ strike, the IRA bombing campaign, race riots, radical feminism) and abundant evidence of this is splashed across the walls of the Tate, the images stark and uncompromising; almost starkly alien within the neutered de-politicised sludge that forms the foundation of our complicit 21st century existence. In this setting, Peter Kennard’s still striking ‘Haywain with Cruise Missiles’ – the jarring insertion of three nuclear warheads into the idyllic East Anglian countryside traditionally depicted by John Constable – mocks not only the vandalism of the nation’s untouched beauty by foreign missile bases, but also the contemporary notion that the tiresome Banksy is in any way ground-breaking, original or daring.

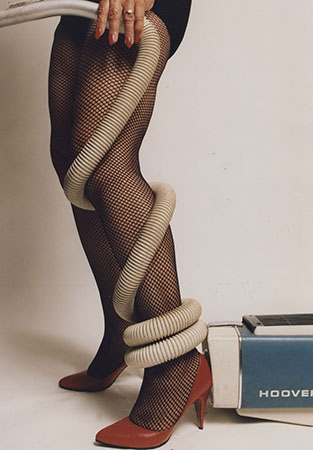

Likewise, Stephen Willats’ bleak 1978 work ‘Living With Practicalities’ empathetically deconstructs the daily experience of an elderly woman living on her own in a West London tower block, the isolation of the elderly symbolised physically and socially by her bleak concrete existence. It is however ‘Libido Rising Part I and II’ by Jo Spence – an eschewer of the term ‘artist’, and self-confessed ‘cultural sniper’ – that best encapsulates the incendiary and confrontational chutzpah of the times, her unapologetically caustic depiction of the female experience played out via provocative images depicting the tyranny of housework and the liberty of self-empowerment. The fetishisation of a vacuum cleaner pipe coiled suggestively around a stockinged thigh acting as a glorious ‘fuck you’ to the likes of Allen Jones and his sado-masochistic artistic oeuvre.

Libido Uprising Part I, 1989

© Estate of Jo Spence, Courtesy Richard Saltoun Gallery, London

Raymond Williams’s key words prostrate themselves across the walls of the Tate in large, looping hand-written script, the ostensible driving forces of this exhibition – Criticism, Private, Myth, Unconscious, Violence – and though Tate Liverpool exposes itself to criticism of stretching the use of Williams’s text to fit a different, albeit complementary artistic agenda, ‘Keywords’ ultimately succeeds in presenting the inharmonious, dystopian sense of a time and a place notwithstanding. ‘Blue Monday’, the political remix film created by the UK scratch video duo The Duvet Brothers, acts as a hugely poignant evocation of a nation’s populace cast to the margins. ‘How does it feel? / To treat me like you do?’ Bernard Sumner implores as scratchy images of police brutality, the Soviet war machine, the miners’ strike and the 1981 royal wedding blur into an incomprehensible and unpalatable whole. In this sense, it is wholly appropriate that this self-contained video booth is situated only a yard or two from a sealed glass cabinet that houses numerous archive copies of The End, a work of ’80s fanzine genius that could only have originated in Liverpool; its unholy collision of terrace culture, savage humour and ‘wool’-baiting underpinned by an inner-city rage steeped in the harsh reality of mass unemployment and urban poverty. That fanzines, disposable and immediately outdated by their very nature, now sit side by side with the work of Hockney (My Parents) and Jarman (Ataxia – AIDS is Fun), says much about the irreverent jumble at the core of Keywords, and much about the city in which it is staged. Suitably, the archive examples of The End cease at 1988, the year preceding the Hillsborough disaster, the year in which the clocks stopped.

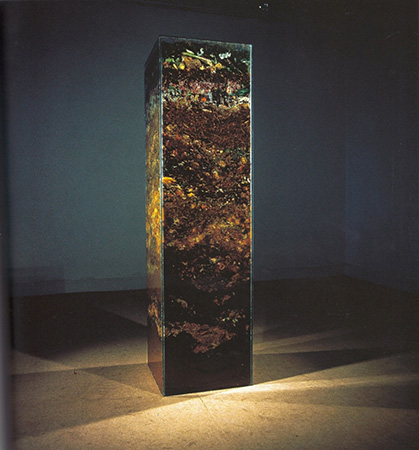

Carcass 1986

Glass tower filled with compost (vegetable detritus)

2133.6 x 610 x 610 mm

© Edward Woodman, Courtesy the Estate of Helen Chadwick.

Love it or hate it, and there are many who hate it with a searing passion,‘Carcass’, Helen Chadwick’s astonishing two-metre high perspex tower of rotting vegetable waste, is undoubtedly Keywords’ standout piece. First exhibited at Chadwick’s solo exhibition at the ICA in 1986, the (then glass) tower initially leaked before jettisoning its slurry-like content during the exhibition’s run, and was removed from display. The mythical status it has taken on in the intervening period inspired a collaborative project at Tate Liverpool, its staff collecting the vegetable food waste that now populates its ominous sealed container. It is a work of art that is constantly evolving, constantly in need of replenishment, and whether it exists to reflect human decay, the decay of our society, or much like Stephen Willats’ work, the social degeneration of tower block living, its provocative multi-layered impact is utterly fascinating. Much like Raymond Williams himself, the late Chadwick saw culture as a medium for political transformation and stood resolutely as an artist determined to celebrate and express a world of explosive possibility. For, as Williams himself was keen to make clear, to be truly radical is to make hope possible rather than despair convincing.

Illustration by Dean Lewis