Newport’s fate, in a high-mobility twenty-first century, is that of Oldham, Wolverhampton, Sunderland. All four cities, home to city centre Victorian architecture of a magnificence of scale and pride, are close – too close by far – to a larger, wealthier, glossier neighbour of a city. For Newport even its most distinctive landmark, the Transporter Bridge, found itself pinched by Cardiff for that still-looking-good film of 1959 Tiger Bay.

Newport is a city more remarked upon by what it has not got. It has no fine visitor-attracting cathedral. St Woolas, Ann Drysdale narrates, was a parish church until 1921, then a pro-cathedral, and not a cathedral in its own right until 1949. The city castle is a rump marooned on a traffic island. It had a university in its own name, with a distinguished track record in media and arts, but that went in the winter of 2012 to join a larger agglomeration. The items of economic news that hit the headlines are more often negatives, led by retail’s most famous name shoving off for an out-of-town motorway-hugging mall.

But a city is greater than tourist locations, shops and sheen. It is its people and Ann Drysdale’s book is filled with them. (On a personal note a great-aunt of mine from Newport was a personality of indistinguishable jolliness; it was from her that I first learnt words like ‘taid’ and ‘nain’.) Drysdale gets to meet Ray who travels constantly on the Transporter Bridge. Frank, at the West Usk Lighthouse, has a device that searches for sounds from ghost or alien sources.

The author’s encounters are encouraged by one factor. A motorway courses right through Newport. For the visitor who leaves the M4, it seems, like Dundee or Leeds, that dual-carriageways are in abundance to speed the car journey. Drysdale characterfully opts for public transport. This turns a fifteen-minute jaunt in a car into a morass of logistical and time tabling complexity. A trip to the Celtic Manor that ought to be a doddle requires telephone calls, advice and the bus to Chepstow. She falls back on a local travel advice line that has been relocated from Gwent to Porthmadog. Her abandonment of the car is engagingly idiosyncratic, but also wise. Foot is the means by which humans were built to experience place.

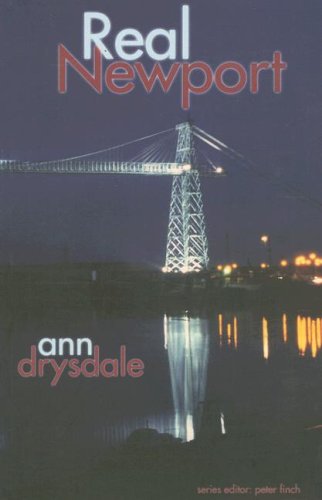

by Ann Drysdale

176pp, Seren

Readers in the travel genre can expect several things; personality is one. Drysdale has Otis the dog as companion for a canal-side walk. He gets his own photograph in a drenched condition. At the Riverfront she delights in the cakes ‘not only because they are wicked and delicious but because they also have bizarre and beautiful names.’ Looking at historic bullet-holes she dryly observes that they occur ‘exactly where a person hanging a gate might have drilled them.’ The prose also comes, uniquely, interspersed with her own verse – ‘The call of nature, the call of man/ Had drawn him to the bosky bank/ For a Jimmy Riddle, a J Arthur Rank.’

She is also a writer. At the Llanwern plant her contact is named Tom. As all attempts to find him flounder she remarks on the ‘recherche de Tom perdu.’ She is a former journalist with the South Wales Argus, as good a training as it gets, and one that she evokes with affection. A fellow journalist with a sizeable cheese-plant on his filing cabinet ‘peered from its fronds like a well-groomed marmoset.’ She describes the traditional dish of a half ‘n’ half, a blend ‘alleviating the angst of the lager-laden as to whether they should opt for health or comfort in their choice of evening emetic.’

Travel writing is not history but it roams across history as it needs. I had thought that the status of Wales’ largest town had moved from Merthyr to Cardiff but in the 1830s it was boomtown Newport that outstripped both of them. The Orb Steelworks, opened in 1898, was an offshoot of a West Midlands company and so gave rise to the streets with names like Bilston, Walsall and Handsworth. Hans Feibusch, the creator of forty church murals over as many years, had featured in Goebbels’ exhibition of degenerate art alongside Klee and Kandinsky. A manacled Houdini jumped off the town bridge in March 1913. Kurt Cobain and Courtney Love were involved in a minor car accident in 1991. Terry Matthews’ knighthood prompted a telephone call of complaint from the Premier in Ottawa to his counterpart in Downing Street that it breached protocol that a Canadian citizen be awarded an honour by a foreign state.

Real Newport was published in 2007, the second in Seren’s series after editor Peter Finch’s own exploration of Cardiff. Some things have changed. It is the Newport of before the Ryder Cup. Corus has become part of the Tata empire. Newport’s next most high-profile entrepreneur, and a battler for the city, is a successful retailer of children’s clothes. Europe’s biggest server farm, vast and concrete-entombed, is located a stone’s throw from the elegance of Tredegar House. The subjugation of the Gwent Levels with another motorway has nudged marginally closer to realisation.

No two people ever see a place in quite the same way. The Central Building on the Caerleon campus, with its foundation stone laid by Lloyd George’s fellow Liberal, Reginald McKenna, is a building of pride and confidence. Drysdale spends her time in Caerleon in the company of the ninth century monk Nennius. She acknowledges help from the representative for Newport West, a back-bencher of distinction and integrity, but he appears only to add a wry comment on an item of abstract art.

She closes her book with a line of verse ‘We are the Estuary folk, the children of Mud.’ Yes, there is a lot of mud at low tide and maybe it smells, as she says, of cattle-farts. But to see the Usk on a summer’s night at high tide, next to the twenty-first century footbridge and university building, is to see a sight of grandeur that is somehow absent at down-river Taff or Tawe.

Real Newport has the characteristics of the proper travel writer. It is not to be without judgement but to have a curiosity in whatever a place throws up. She actually has an interest in what an industrial plant does, and how it works. The author in the Seren series who turned his back on a world centre of research, not over-common in Wales or indeed Britain, on the grounds that it was ‘boring’ is not unique. But social reality does not reside in the studios of artists or clusters of poets. Real Newport at seven years of age looks good. For this reader it prompts a journey, book in hand, to Stow Hill, Belle Vue, Coed Melyn, and fast.

Banner illustration by Dean Lewis