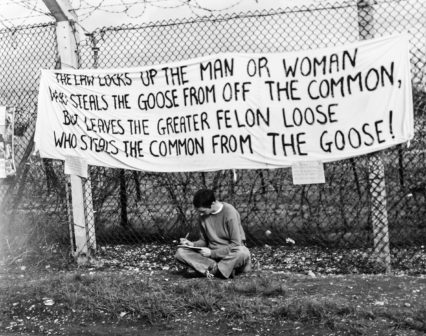

In 1981, a group of women marched from Cardiff to the Greenham Common RAF base to protest against the holding of US nuclear missiles on British soil. This first act of protest became the trigger for the establishment of the Greenham Women’s Peace Camp which remained at the RAF base for almost 20 years. The camp became a hub of activism, attracting 30,000 women and girls from across the UK to “Embrace the Base” in a protest which saw the women hold hands around the 9-mile perimeter of the military enclosure. Now, marking the 40th anniversary of that first march from Cardiff to Newbury, Rebecca Mordan and Kate Kerrow share their book, Out of the Darkness: Greenham Voices 1981-2000, a work documenting the vast range of stories from Greenham women and their memories of their time at the camp.

Caragh Medlicott caught up with Rebecca Mordan – herself a Greenham child – to hear more about the importance of activism, the process of archiving women’s history and how the stories of the Greenham women might be used to inspire a new generation of activists.

Caragh Medlicott: I’m interested to hear what you think about the way we record history, something which – obviously – has predominantly been left to men. But even with this much more recent history, it feels like the Greenham women have started to slip from collective memory. I wondered how you came to the decision to commemorate this moment in time through individual stories and with that, whether the duplicity of authorship was important to you and Kate?

Rebecca Mordan: Good question – there’s a personal answer and a wider answer, I suppose. The personal answer is that my mum first took me to Greenham when I was young, and I was very aware of what a massive difference that made in our lives – how it changed and radicalised my mum as a feminist and how it changed how I was raised. My upbringing made me very conscious, so I went into peace activism and women’s rights activism myself. My mum was really just a visitor and supporter of Greenham, but when I was there I met lots of women like – for example – Helen John, who was really pivotal to the long-term life of the camp.

My mum died about nine years ago, and Helen John died three years ago, and I started to realise that there’s no one younger than me who knows or has heard what it was like – especially considering that it was such recent history. This is within living memory for a lot of women, but no one younger than 40 has been told about it at all. I thought that was really shocking and I don’t think it’s just a coincidence – it seems to fit a pattern of women’s issues being blotted out. I thought it was a really shocking admission. Women inspire women, don’t they? So if you selectively ignore them then the next generation has to constantly reinvent the wheel and it takes us longer, overall, to promote and affect change.

Caragh Medlicott: And that motivated the decision to do the book?

Rebecca Mordan: Well, I spoke to Kate – she knew my mum – and she was focussing on this fantastic online resource called The Heroine Collective, so she was already really good at putting women back into history. It just seemed like a really perfect partnership. At first it started as an archiving exercise, a way of making sure these stories don’t just die with these women. We wanted them to last in some form – otherwise it’s essentially cultural robbery. Then it came about how we could share these stories, get them into places where young women could access them. We put a shout out in the media and our publisher at The History Press approached us with the book idea. She didn’t necessarily have a strong view of what that should be, only that it needed to come out this year for the anniversary.

I think it was important to all of us that if we were going to access these women’s stories, that it would be women doing the interviews. We also liked the idea of multiplicity. Voice is so important in how we record history. It used to be that history was written by the victors, and if you’re a social historian you try to be broader than that. But even so the whole way we archive stuff tends to place emphasis on one person channeling things, but Greenham was leaderless and non-hierarchical. All their decisions were collective decisions and that’s a lot of responsibility. So we just thought approaching it from these different perspectives was the only way to do it right. Our job was just collation, really, the actual authorship comes from all the women and the interviewers.

Caragh Medlicott: So the actual method of recording the history becomes a part of the process.

Rebecca Mordan: Yes, it’s made me think much more laterally about how we record and archive history in general. And I think it’s really important that we get away from the idea of top-down hierarchical kind of patriarchal academia. I think it has to be collective. And even the experience of fitting all these accounts into a lateral book, with a longitudinal structure, it’s been interesting. Actually one of our partners is London School of Economics and they’ve been putting all of our archive work online in their women’s library and had great talks with us about how that entire process functions.

Caragh Medlicott: The women you trained to conduct these interviews are from all over the UK, with ages ranging from 18-80, was that diversity important? What did the process of training them to extract these stories look like?

Rebecca Mordan: Actually, this is something really important to touch upon because the interviewer is as involved as the interviewee in setting the tone and bringing forth the stories – but also, the camp had this really diverse membership. You know, there were women from all different backgrounds, sexualities and classes and we wanted to represent that in the interview team as well. We didn’t want anyone to feel alienated from their interviewer – we didn’t want to just take a middle class academic approach. So doing that felt healthy and representative of Greenham itself.

In terms of the formal process, we worked with the University of West England. We basically put a shout out seeking volunteers and selected about fifteen of them who all went to a day of training with two of the academics who were working with us on the project. They talked us through the formal interviewing process, but then also a more informal approach. In the end we opted for the informal approach and it was on that day we put together the list of questions that we would cover. But there was flexibility, people felt differently about the interview process: some were confident, some were a little more anxious. Some people felt they wanted a lot of questions which they could stick to quite diligently while others, like me, felt more laid back and chatty. Of course, that’s reflective of the ranges of ages and experiences of the interviewers. I think you can probably tell, when you read some of these accounts, when somebody was sticking closely to the script and those who might have taken a more ad-hoc manner. We made the choice, consciously, to be quite verbatim so that the voices shone through in the book.

Caragh Medlicott: It feels like a very deliberate rejection of a kind of cold omnipotence which sometimes comes through in historic accounts.

Rebecca Mordan: Exactly. And of course everything is purely subjective. We’re emotional beings who experience the world through our emotions. To believe anything else is ridiculous – so the best chance we’ve got of being fair in our recounting is to keep that dialogue open and gain a collective perspective.

Caragh Medlicott: And I understand that you were part of Embrace the Base? How old were you?

Rebecca Mordan: I was five.

Caragh Medlicott: Do you remember it?

Rebecca Mordan: Yeah, I do. I mean, sometimes people ask me specifics about the morning getting ready and I’m like – I can’t remember, I was five! But I do remember visiting the base when it was quiet. And I remember being able to ask these women anything I wanted, which outside of that environment adults just didn’t do. In hindsight they were probably very patient with me.

I do also remember Embrace the Base, specifically, because all you could hear was thousands of women singing the same song which is just – mad – and then we all held hands. I remember my mum explaining what was going on. It was just an incredibly powerful and uplifting experience. Becoming this human fence, encircling all this harsh military stuff on the inside and seeing all the police patrolling on the outside. I can still remember how some of the policemen would look at you and smile, and how others didn’t really engage and could even be hostile. It was fascinating. It was an insight into the adult world and the power of women. I remember looking at the grown women around me and thinking, wow, one day I’m going to be like them. That was just like, wow.

Caragh Medlicott: That idea of the song and singing seems to come through a lot with this, as both a symbol of unity and of protest. I wonder if there’s a gendered aspect in the sense that women’s voices are so often talked over, was song a way of combating that?

Rebecca Mordan: Yeah I think there are two things going on with the singing, and one of them definitely has a gendered aspect. There are gender stereotypes about who can use their voice, I remember reading a study a few years ago that talked about conversation perception. It was about how much space women could take up in a conversation before men felt they had too much dominance. So, when women took up a quarter of the conversation, men perceived them as having taken up half the conversation. And there’s also that thing about when women can use their voices, and how they adapt them. I’ve noticed, myself, that when I’m talking to a man I don’t know, I’ll go quite high in pitch. I’ve started referring to it as my “good girl” voice! Now I’ve clocked that I try to catch myself doing it.

I think there are also some stereotypes about men not really being able to sing. I mean, it’s brave to sing, isn’t it? It’s performative but also vulnerable. In general there isn’t as much of a thing around male singing like there is around, say, sports. I mean except in parts of Wales, where there are male choirs that are very much about masculinity, but for the most part I think it’s more associated with women. One of the silver linings in the patriarchy is that women are afforded these softer skills, but then they become quite segregated and men aren’t a big part of them. So I think it was almost just automatic that the women there were drawn to singing.

I think the other aspect of it is that it’s really about non-violent direct action. It’s a way of pulling on your inner reserves – using your core muscles. And women can make all kinds of sounds. It’s not just pretty songs, you can really come out soulful and angry. The Greenham women actually made some very disturbing noises to express their fear and their anxiety and their rage. And – as you say – it absolutely unified them. They had to face down police without attacking or hurting anyone. There’s a song that they used to sing a lot about how you can’t kill the spirit, it’s remembered by anyone who visited Greenham. Of course, it was quite repetitive so it used to drive the women who actually lived there a bit mad. They were over-exposed, I think. But they made up their own songs, too, sort of rewriting popular tunes and retail jingles so that they were playful and irreverent.

Caragh Medlicott: I guess there’s an element of authorship there, too.

Rebecca Mordan: Yes, it’s taking power back. Women aren’t represented enough in culture, in songwriting, in storytelling, in performance – anywhere! It was a kind of bending, recreating culture in their own image. It was basically like playful disobedience, as well as civil disobedience. One of the images the Greenham women came back to a lot was this symbol of the web. They wanted to reclaim negative stereotypes about women, one of them being that of the spider and the mythology of webs and witches which surrounded that. I’ve been thinking about that idea a lot recently. The reach of the webs we create, the way everything is connected. The fact that something as fragile and tiny as a spider can create something as beautiful and complex as a web. You know, a spider can take an existing structure and imprint a presence there, just like the Greenham women did.

Caragh Medlicott: One of the things that really struck me about this entire moment in history is the determination of the women involved. To go from an under-publicised 110 mile walk from Cardiff to the Greenham Common… to the Embrace the Base protest in 1982 with 30,000 other women. Sometimes I wonder how social media has impacted activism today, whether it’s made it easier or whether some of that resilience has been lost to a kind of performativity?

Rebecca Mordan: Well a lot of what the Greenham women did was performative, like the teddy bears picnic [200 Greenham women dressed as teddy bears and entered the base for a picnic protest in 1983]. Obviously we’ve seen more recent examples of performativity with climate change activism and Extinction Rebelion. But I think in a lot of ways the whole ecosystem has changed, we don’t have a welfare state in the same way – a lot of the women who stayed at Greenham survived on the dole. And a lot of the things the Greenham women were doing have been made illegal precisely because they did them. Things around what constitutes trespass and what constitutes damaged property – stuff like that.

So now, with the animal rights movement, the green movement, the anti-fracking movement, we’re at this point where there’s an attempt to enforce increasingly draconian laws. Things like the new policing bill which we really have to fight. That trajectory makes things very different for protesters today. That’s not to say the Greenham women had it easy at all, but they had some support from the dole and better social services. Some of the law hadn’t caught up to them yet, either. But also they were innovating and collaborating to come up with different types of protest. That’s why the law had to innovate around them.

Clearly social media has added another dimension, too. In some ways it’s amazing. We can communicate and leverage people very fast. But equally, it’s easy, isn’t it, to think all the work happens just sitting at our computers. But still I think we manage to share a lot of information through social media interactions. So I’m definitely not against it, either. It’s complex.

Caragh Medlicott: I guess it’s never going to be cut and dried, there’ll always be that nuance.

Rebecca Mordan: Yes. Definitely. I think the thing with culture now is there’s such a rapidity, whether it’s protest or just work-life balance, it can be hard to liberate ourselves from the pace of it. I suppose the only other challenge I’d see to something like a women’s only initiative today would be the debate around what constitutes a “women’s only” space. Having said that I think it can be done, there were so many obstacles the Greenham women overcame. If you get enough of the right minded people together these things can be solved – there’ll be compromise, nuance and debate. But that’s fine! It’s healthy. I think it’s something we need to get better at in general, this no debate thing, because these divisions are just handing our civil liberties over to the patriarchy and capitalism.

Caragh Medlicott: You’d hope with things like the climate climate crisis that there is enough urgency to really push forward rather than squabble amongst ourselves.

Rebecca Mordan: Yeah, we really need to keep our own house in order on the left. I don’t think we can do that by shutting up, I think we absolutely have to talk to each other. I mean Greenham was brilliant for that. Women would get together, sit down, side by side, and they’d argue and debate and challenge each other. It would get really heated, even nasty. But then the next day they’d take each other’s hands and face down police vehicles together. That’s what we need to learn to do again.

Caragh Medlicott: What else do you think women activists, today, can learn from the Greenhamn women? Is there any particular advice you’d give?

Rebecca Mordan: Well, firstly I’d say come join us. Anywhere from 26th August to 5th September we’ll be out walking the route the Greenham women took. All the details are on the website. It’s a huge celebration and anyone who comes will meet tonnes of amazing women from that time… which brings me to my other piece of advice. Talk to women! Talk to your mums and your grandmas and your aunts. Talk to the women who participated in second wave feminism, we owe them so much; the women who fought for equal pay, to make domestic violence a punishable crime, to make rape in marriage illegal. It’s so easy to get stuck in your own bubble but there was a whole generation of women who sorted that shit out for us. When you actually connect with these women you really do realise you’re standing on the shoulders of giants. That’s not to say you have to agree with everything they did or take all the advice they give, but that we should at the very least build on top of what’s already been built. We don’t need to reinvent the wheel – we just need to keep progressing forward.

Out of the Darkness: Greenham Voices 1981-2000 is available via The History Press.

More information on the 4oth anniversary walk is available here.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.