2022 marks ten years since the launch of Wales Arts Review, and as part of our celebrations, throughout this year we’ll be revisiting some of the best and most loved features, interviews, and reviews from our archive of nearly five thousand published pieces. Today, we take a look back to 2020 when the writers at Wales Arts Review came together to select what they thought were the 50 most innovative horror movies of all time ready for Halloween. Are you wondering what to watch? Rosie Couch, Gareth Smith, Rob Lloyd, Gary Raymond, and Gray Taylor have you covered. In no particular order, here are films to keep you busy this Halloween.

1. Mandy (2018. Dir: Panos Cosmatos)

Red Miller (Nicholas Cage) and Mandy Bloom’s (Andrea Riseborough) comfortable coupledom is disturbed when a cult named the Children of the New Dawn passes through their quiet, lakeside life near the Shadow Mountains in California. Cult leader, Jeremiah Sand (Linus Roache), is entranced by Mandy. At first sight, he decides that he must have her. With help from the Black Skulls – a demonic biker gang whose addiction to a powerful form of LSD has formed them into an otherworldly combination of human and beast – the Children of the New Dawn captures Mandy with the intent of absorbing her into the cult. Red, however, is not the kind of man to take this lying down. Cage’s characteristic excess is put to spectacular use in Mandy, charged by love and rage, and accompanied by Icelandic composer Jóhann Jóhannsson’s (Arrival, The Theory of Everything, Blade Runner 2049) final score. If you thought Mandy’s folk singing hippies and brutally violent bikers didn’t render the film generically slippery enough, you’re in for a treat. From its sword-and-sorcery quest narrative and chainsaw wielding fanaticism, to the trippy mise-en-scène and rhythmically precise action sequences, echoes of existing cinematic and fictional worlds are strewn masterfully and innovatively throughout. RC

2. Peeping Tom (1960. Dir: Michael Powell)

To the uninitiated Peeping Tom has always seemed a rather deranged right angle in Michael Powell’s glittering career as the one half of the Powell-Pressburger phenomenon. Archer Productions, their film company, is often remembered as creating rather dated, placid, quaint English movies about Englishness. But when Peeping Tomcame out and shocked the world it was just another in a long line of innovative, gritty movies from one of the truly great directors of the era. The real shock of Peeping Tom is not that the serial killer is sadistic, or that he is insatiable, but rather that Powell puts the audience in his seat. As the excellently cold Carl Boehm murders the young girls he lusts after, he films them, trying to capture their terrified dying expression on a hand-held camera. Powell puts us in the lens, we see what the murderer sees. It is a cruel and powerful trick that ended Powell’s illustrious career – nobody would work with him or show his films after Peeping Tom. The man who brought us A Matter of Life and Death, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, The Red Shoes, Black Narcissus and countless other movies that will forever be listed in the greatest movies of all time was undone by his own artistic vision, and the power of the horror movie. A movie powerful enough to end that career must be worth experiencing. GT

3. Suspiria (1977. Dir: Dario Argento)

Dario Argento’s Suspiria (1977) depicts the arrival of American ballerina Suzy Bannion (Jessica Harper) at a prestigious German dance academy and her subsequent discovery of terrified students, terrifying staff and a series of grisly murders. Co-written by Daria Nicolodi, the plot begins by focusing on the doomed women and bloody violence characteristic of the Giallo genre before moving towards the supernatural when Suzy uncovers the academy’s connection to a coven of murderous witches. Suspiria’s influence lies partly in the effective creepiness of its pacing and the shock of its violent set-pieces, but its legacy is primarily stylistic. The cinematography favours vivid colours; the inside of the academy is shot in painfully striking red, green and blue. The argument that horror films are equally as scary when shot in bright colours as they are in the dark has recently been demonstrated by Ari Aster’s Midsommar (2019). The film builds to a climax in which Suzy comes face-to-face with the concealed founder of the academy and Argento uses shadow, light and music to produce a far greater terror than direct depiction would have. While the film was remade in 2018 .with a more self-consciously arthouse aesthetic, the original still has the power to both disturb and dazzle several decades later. GS

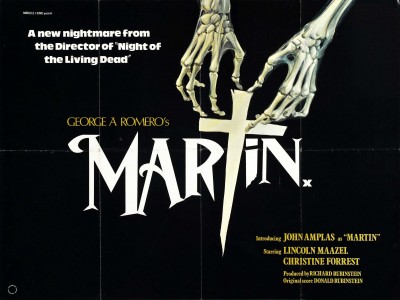

4. Martin (1977. Dir George A. Romero)

4. Martin (1977. Dir George A. Romero)

George A. Romero is, and probably always will be, best remembered for his contributions to the Zombie Horror canon, with such iconic films as Night of the Living Dead (1968) and Dawn of the Dead (1978). Yet his innovations in Horror were broader than this association with reanimated corpses, and nowhere is this more apparent than his 1977 film Martin. The eponymous protagonist (John Amplas), driven by an insatiable desire for blood, preys on a series of women in and around the city of Pittsburgh. To all intents and purposes, he’s a modern-day Dracula. But what exactly does this mean? Romero’s film deconstructs literary characterisations of the vampire as a human-animal hybrid figure of potent sexual transgression. No fangs and stealthy night-time visits for Martin; his preference is for sedatives and razor blades, and the encounters with his victims are anything but confident. Romero uses vampiric lore and terminology – Martin is referred to as ‘Nosferatu’ and ‘The Count’ by various people throughout the film – to question the limits of its definition. What makes someone a vampire? If a person believes themselves to be one, and acts accordingly, is that a distinction without a difference? Leaving this unresolved not only makes Martin one of Romero’s most memorable films, but marks it out as an intensely interesting and original iteration of one of Horror’s most iconic monsters. RL

5. Jennifer’s Body (2009. Dir: Karyn Kusama)

Hell is a teenage girl. Or so suggests Anita ‘Needy’ Lesnicki (Amanda Seyfried), from the solitary confinement of the facility in which she is now imprisoned. Set in Devil’s Kettle, Minnesota, Jennifer’s Body is a supernatural horror and black comedy, reflecting on Needy’s friendship with Jennifer Check (Megan Fox), and the events which both tore apart and intensified their connection. Needy, once meek and bookish, accompanies her best friend – the beautiful and popular cheerleader Jennifer – to a gig where rock band Low Shoulder are playing. Jennifer leaves with Low Shoulder and, we later discover, is used as a sacrifice to Satan in exchange for the band’s fame and fortune. That old chestnut. The problem is, they believed that Jennifer was a virgin. The ritual goes wrong and, as a result, Jennifer becomes a demonically possessed succubus, finding nourishment through feeding on the boys at school. In this dynamic alone, the teenage girl’s relationship to consumption in popular culture – and in horror more specifically – is turned on its head. Despite this subversion, contemporaneous responses were reductive, branding Jennifer’s Body as ‘Twilight for boys’, or describing the film with a bitingly original ‘Hot! Hot! Hot!’. Though recent reappraisals of Jennifer’s Body have sought to highlight the feminist merits of Kusama’s film, it remains to be a criminally overlooked study of the complexities of female friendship, embodied experiences of teenage girlhood, and the capaciousness of horror to construct both. RC

6. Audrey Rose (1977. Dir: Robert Wise)

It’s perhaps fitting to start this countdown with an unsung corker from the director of cinema’s greatest ghost story, Robert Wise. Audrey Rose is not really a horror movie in the traditional sense, but like some others that get thrown into this genre (like Let the Right One In or The Babadook, for instance) it is a film about grief, loss or loneliness, that uses elements of supernatural storytelling to explore the depths of the subject. Here, an excellent Anthony Hopkins plays the aggrieved father certain that his daughter is reincarnated in the form of a little girl (Susan Swift), and the always magnificent Marsha Mason is the mother who gradually comes to believe it to. There is much to chill the bones, and Wise knows how to pace this type of thing perfectly, but it is perhaps the emotional impact that will stick with you. GR

7. Scream (1996. Dir: Wes Craven)

Primarily associated with the image of a scared teenager answering the phone and the line “What’s your favourite scary movie?”, Scream established a dialogue between horror and its audience which permanently reshaped the slasher genre. Since their heyday in the era of Halloween (1978) and Friday the 13th (1980), slasher films and their innumerable sequels were considered tired, repetitive and laughable by the mid-nineties. Established horror director Wes Craven and scriptwriter Kevin Williamson rejuvenated the genre by gleefully subverting its conventions. The teenagers of Scream know all about scary movies and this meta-humour, combined with dialogue sharp enough to skewer any cliches, made films about teenagers pursued by masked maniacs seem fresh, funny and relevant again. Protagonist Sidney Prescott (Neve Campbell) is also a decisive progression within the ‘final girl’ archetype, demonstrating a snarky attitude and ability to fight back lacking in her antecedents. While numerous sequels (including an upcoming fifth installment in 2021) have made it the sort of never-ending franchise that the original mocked, the influence of the first Scream means it is now almost impossible to make a slasher film without a knowing smirk on its face. Its ongoing impact is evident in more recent fare such as The Final Girls (2015) and Happy Death Day (2017). GS

8. Possum (2018. Dir: Matthew Holness)

To put it simply, Matthew Holness’s Possum is unlike anything I have watched before. Based on a short story of the same name, Possum follows Philip (Sean Harris) a former children’s puppeteer, as he returns to his childhood home, now solely inhabited by the unsettling uncle Maurice (Alun Armstrong). Possum, a horrible, spider-like puppet, is in tow. While visiting, a boy goes missing and Philip is thought to be a suspect, partly due to his sudden reappearance, but also his suspicious wanderings around his old school, the disused barracks, and the woods. But Philip hasn’t been meandering without purpose. Rather, the drab circularity of his walks have been part of attempts to finally get rid of Possum. Try as he might, Possum always returns. Sometimes, Philip even goes back for him. As an exploration of the Freudian uncanny – concerned with the revelation of what is concealed, the return of the repressed – Possum is sparse in dialogue and jump scares alike. As a result, Possum’s visual vocabulary works hard to create a dreary and disquieting atmosphere throughout. Though puppets and dummies are a frequent fixture of contemporary horror, in The Boy (2016) or Annabelle (2014), for example, Possum’s puppet-horror is both distinctive and difficult to forget. RC

9. Housebound (2014. Dir: Gerard Johnstone)

A strangely compelling, genre mash up that works on all the levels it attempts. The term horror-comedy makes most people shudder in fear. But this New Zealand low budgeter is genuinely nerve tingling, intriguing, and funny, even pulling off some successful slapstick. The actors’ performances are pitch perfect and the story absolutely beguiling, eventually. Fun for all the dysfunctional family. GT

10. Amer (2009. Dirs: Hélène Cattet and Bruno Forzani)

This homage to Italian gialli is less innovative than it is appropriative, thriving off the cinematic excess of directors such as Dario Argento, Mario Bava and Emilio Miraglia. The tripartite narrative centres on Ana at three stages in her life (played by Cassandra Forêt, Charlotte Eugène Guibeaud and Marie Bos respectively). At the beginning of the film, she lives in a sprawling clifftop manor overlooking the French Riviera, where she first begins to make a connection between the twin impulses of sex and death; this is also the place to which she returns in the film’s third segment, as the logical end-point of the increasingly sinister explorations she makes of the boundaries of her (sexual) identity. Amer is a film that positively (and self-consciously) vibrates with Freudian resonances, being less a coherent narrative than a series of sensory impressions. Horror fans will recognise the influence of such intertexts as Argento’s Deep Red (1975) and Suspiria (1977), as well as Bava’s Shock (1977), with the film playing off their intensely stylised and colourised cinematography and disorienting soundscapes – short on dialogue, but big on effect. The film is both a pastiche and an exploration of giallo conventions, which, although purposefully imitative, illustrate that the genre still has the capacity to overload its viewers with a delirious sense of Gothic extravagance. RL

11.The Haunting (1960. Dir: Robert Wise)

The greatest haunted house movie ever made, and still, inexplicably, often missing from movie lists, Robert Wise created a film that very few directors or studios have had the guts to try and copy in the decades since. It is almost a cliche that the audience gets to see nothing in The Haunting – all of the scares are made through the power of suggestion – but it is the lack of the ability of the genre to recreate what Wise did that really marks his achievement. (Perhaps a fine display of this is in how the 1999 remake fills in all the gaps Wise left with CGI special effects to create one of the shittest films of all time). The premise is simple – a professor exploring supernatural goings on at the infamous Hill House invites a few carefully selected youngsters to stay a few nights with him. It is, of course, the house that is the villain, the house that will prey on the vulnerable, with all of its uneven angles and twisting staircases. If your idea of a great Halloween is a blanket pulled up to your nose having the bejeesus scared out of you by the things that go bump in the night, The Haunting is the movie for you. Just make sure you check whose hand you’re holding. GR

12. The Babadook (2014. Dir: Jennifer Kent)

In Jennifer Kent’s directorial debut, Australian horror The Babadook, Amelia Vanek (Essie Davis) lives alone with her son Samuel (Noah Wiseman). Her husband died in a car accident when he was driving Amelia to the hospital when she was in labour with Samuel. Amelia’s strain to keep things together, push aside her own anxieties, and care for her son are foregrounded in the dazed way in which she navigates, or perhaps avoids, the world of grieving. Cue the Babadook. First introduced as a character in a book mysteriously found by Samuel, the Babadook is a strange, tall creature with long fingers and a hat. Samuel is upset by the book, but adamant that the Babadook is real. Amelia tries to dispose of the book but it reappears with an additional warning – the more she tries to push the Babadook away, the stronger he will become. It is here that the disruptive Babadook is easily aligned with experiences of grief, and how repressed trauma can bubble back to the surface in unexpected ways. Overall, refracted through the trappings of psychological horror, The Babadook is a refreshing and yet terrifying study of grief and maternal ambivalence. RC

13. The Howling (1981. Dir: Joe Dante)

Ask someone to name the werewolf film from 1981 whose transformation scenes were the most remarkable ever committed to celluloid, and which would forever change the Horror genre, and they’ll almost certainly say. . . An American Werewolf in London. This is the other one. Joe Dante’s The Howling tends to get eclipsed by its more expensive, more successful Oscar-winning cousin, which is a shame because it more than holds its own as a film that helped to revitalise cinematic depictions of lycanthropy. The story focusses on Karen White (Dee Wallace), who, suffering with traumatic amnesia after a run-in with a serial killer, is sent to a resort in the countryside surrounding Los Angeles – referred to as ‘the Colony’ – to facilitate her recovery. The only downside is that it’s a colony of crazed werewolves, capable of transforming at-will, and intent on preventing Karen from making it back to the city unbitten. Considering the budgetary constraints, the transformation scenes are as gloriously rubbery and freaky as those in Landis’s film (the latter’s special-effects artist, Rick Baker, had originally been working on The Howling, which accounts for some of the aesthetic similarities). The film undoubtedly has its silly moments – including some less-than-convincing campfire ‘mating’ – but it’s also driven by ideas, from trauma as a form of monstrosity to public desensitisation through media, which took it in new directions from its furry brethren. RL

14. Daughters of Darkness (1971. Dir: Harry Kumel)

14. Daughters of Darkness (1971. Dir: Harry Kumel)

The fear of the vampire lies in the allure, the danger of wanting to be seduced despite the consequences. By the 1970s the more astute filmmakers were tapping into that with varied results, and although Harry Kumel’s Daughters of Darkness is without doubt a very sexy film, it would be unfair to lump it in with other horror erotica of that period. The original title explains a great deal in Kumel’s vision: Les Levre Rouge, (The Red Lips). This is a film about the only two things everyone on earth obsesses about – sex and death. Daughters of Darkness is exceptionally strange, exceptionally beautiful, and the sex comes from a fundamental understanding of the fears of desire and the ultimate vulnerability in those moments of physical relinquishment. In Delphine Seyrig we have the ultimate temptress, slitheringy sexy, oozing a kind of Weimar-Berlin cool; she treads a very thin line between sympathetic and appalling. It has style to spare, its punches are brutal, and at its heart there is a political message amid the tragic romanticism – that women are destined to be slaves to men in the current system of things. A movie that fully understands our fears, when you talk of the great vampire stories, this film must count among them. GR

15. Rec (2007. Dirs: Jaume Balagueró and Paco Plaza)

For want of more refined terms, Jaume Balagueró’s Rec (2007) delivered a much-needed kick up the arse to the found-footage genre of horror films. The shaky camcorders of The Blair Witch Project are replaced with the equipment of a TV news camera crew, sent to report on a fire at an apartment building in Barcelona. This allows for the spontaneity and dizzying perspective of the found-footage film to meet the more professional aesthetic of a television camera. Locked inside by the authorities, reporter Ángela Vidal (Manuela Velasco) discovers that the residents are suffering from a highly infectious disease that transforms them into rabid, flesh-hungry zombies. The confined space of apartment building and its numerous rooms ensure a continual fear of monstrous faces emerging from doorways and each sound, no matter how insignificant, takes on additional menace in the dark. The initial diagnosis of the disease as a form of rabies is complicated by hints that demonic possession has taken place, creating an interesting intersection between religious horror and science fiction. The film inspired numerous sequels and an American remake, Quarantine (2018), but its impact on expanding the possibilities of found-footage horror can also be traced in the Paranormal Activity franchise. GS

16. Kuroneko (1968. Dir: Kaneto Shindo)

It will be difficult to argue there is a more beautiful horror film on this list than this delicious black and white Japanese interpretation of an ancient folk tale. The title translates as ‘A Black Cat in a Bamboo Grove’, but it has so much more depth and artistry than the insinuation that this is a prowling movie, a movie waiting to pounce. It is, in essence, a supernatural revenge tragedy; the spirits of a mother and daughter raped and murdered by itinerant soldiers return to exact a frenzied retribution. But Kaneto’s artfulness, his use of the shadows from the hanging trees to the folds in the clothes, meant that Kuroneko was a shoe-in for the Palm d’Or in the year the Cannes Film Festival was cancelled due to civil unrest. It’s a shame the award might have made it more of a household name. GR

17. From Beyond (1986. Dir: Stuart Gordon)

After updating and twisting HP Lovecraft in Re-Animator, Stuart Gordon went even further with his next Lovecraft adaptation, From Beyond. A surreal, wild horror film that twists and turns like the gooey creatures that inhabit it. More classic performances from Re-Animator‘s Barbara Crampton and Jeffery Combs, as well as Dawn Of The Dead’s Ken Foree, mix with Gordon’s unique vision of body horror to make this an absolute eighties horror classic. GT

18. Raw (2016. Dir: Julia Ducournau)

When Justine (Garance Marillier) begins studying at veterinarian school, she is involved in a hazing ritual in which the new class is covered in blood before being told to eat a rabbit’s kidneys. Justine, a vegetarian since birth, initially refuses to take part, but is eventually forced to consume the meat by her older sister, Alexia (Ella Rumpf). She wakes the next day with an extensive, itchy and bloodied rash, craving meat. Justine is ashamed of this new desire but eventually gives in, discovering that animal flesh is not satisfying her hunger. In fact, consuming raw chicken causes her to vomit human hair. She is diagnosed with food poisoning, but when a waxing accident causes Alexia to lose the tip of her finger, which Justine eats, it becomes clear that her cravings are not just for any old animal flesh – she needs to eat humans. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Raw has been categorised as belonging to the New French Extremity movement in horror cinema, due to its heavy investment in body horror and cannibalism. Like Jennifer’s Body, however, there are also interesting ideas at play in terms of Raw’s construction of the consumed/consuming teenage girl, interconnecting ideas around virginity and sexual initiation, as well as cannibalism as a transgressive desire, a breaching of the boundaries of self and other. RC

19. Get Out (2017. Dir: Jordan Peele)

Jordan Peele’s Get Out (2017) was a huge success for mainstream horror: commercially successful, critically acclaimed and enjoying the rare accolade of being an Academy Award nominated horror film. Its success lies in its suspenseful tone, strong central performances and Peele’s skillful direction, but its central storyline was also both timely and significant. Chris (Daniel Kaluuya) is a black photographer visiting his white girlfriend’s new family, all of whom are keen to stress their credentials as liberals and demonstrate how welcoming they can be. Despite their benevolent appearance, Chris begins to notice the strange control that they exert upon their black employees and acquaintances. What begins as a metaphoric satire on the policing of blackness by insidious forms of white supremacy quickly becomes literal as mind-control and body-swapping allows for actual physical appropriation. The film effortlessly combines social commentary with science-fiction and uses disorientating surreal imagery during the film’s infamous hypnosis scenes. As well as creating a stronger appetite in cinema audiences for horror films generally, Get Out also highlighted the overwhelming whiteness of the genre (in terms of creative talent and the stories themselves). Peele’s next film Us (2019) and Nia DaCosta’s upcoming remake of Candyman (2021) suggest that this desire for change continues to gather momentum, hopefully indicating that Get Out will prove something of a turning-point for racial representation within mainstream horror. GS

20. XX (2017. Dirs: Jovanka Vuckovic, Annie Clark, Roxanne Benjamin, and Karyn Kusama)

XX is a horror anthology consisting of four short films: The Box (Jovanka Vuckovic), The Birthday Party (Annie Clark), Don’t Fall (Roxanne Benjamin), and Her Only Living Son (Karyn Kusama). In The Box, a woman, her son, and her daughter sit next to a man on a train who is holding a box. He claims that there is a gift inside, and lets the son take a peek. Soon after, the son stops eating. His sister and father follow suit. What was in the box? Replete with near misses and excruciating tension, The Birthday Party features a mother juggling the discovery of her husband’s corpse, and the impending start of her daughter’s birthday party. In Don’t Fall, the pranks and shenanigans of friends on holiday are stopped short by a monstrous transformation. Will anyone make it out alive? And, last but not least, Her Only Living Son constructs a mother’s struggle to keep her son close, as the knowledge of his diabolical paternal figure seeps into the community around them. Interwoven through each short film are themes of domesticity, maternity, the body, and control, expertly foregrounded and stitched together by the creepy stop motion frame sequence. The collection of these shorts into a longform piece is an innovative move, allowing the aforementioned interplay of themes to operate, while supporting the smaller budgets of filmmakers from a range of contexts. RL

21. Hour of the Wolf (1968. Dir: Ingmar Bergman)

It is a gift from whichever supreme being you ascribe to that Ingmar Bergman directed Max von Sydow and Liv Ullman in what is only superficially described as a psychological horror film. Like all the greats, it is so much more than just that, but in this case the greatest film director of them all put two of cinema’s finest actors on a remote Swedish island, washed them in monochrome and steered them toward delirious, surreal, murderous madness. This is the film everyone who thinks The Shining is the greatest horror movie of all time should see, so that they can understand what psychological disintegration truly looks like, but also that Kubrick was a vaudevillian compared to Bergman. The surreal scenes in the final chapter are not only haunting, they have a punch as stark as the Swedish landscape. Bergman always drew on his deepest feelings and experiences for his films. Poor sod. GR

22. The Fly (1986. Dir: David Cronenberg)

Few directors have so completely dominated a subgenre as David Cronenberg has with body-horror. Through early films such as Shivers (1975), Rabid (1977), and The Brood (1981), Cronenberg gradually perfected the art of anatomical atrophy that finds its most famous expression in his 1986 remake of Kurt Neumann’s 1958 original. Seth Brundle (Jeff Goldblum), an archetypal idiosyncratic-but-brilliant physicist, falls in love with Ronnie Quaife (Genna Davis), a science journalist who agrees to write a story about his work developing a teleportation device. During a demonstration, Seth’s DNA is spliced with that of a fly, setting off a series of increasingly disgusting physical and emotional transformations in the unfortunate scientist. Cronenberg’s depiction of the human body in terminal crisis is not merely centred on the infliction of pain without context, but is rather an effect of and metaphor for a deep-rooted concern about individual capacity for suffering in circumstances over which there is little control to be exerted. Seth Brundle is, ultimately, a tragic figure, and it is this capacity for Horror to be both vomit-inducing and intellectually stimulating that really encapsulates the importance of The Fly to the genre. Through this (sub)genre-defining film, Cronenberg reminds his audience that (most) Horror is not mindlessly in favour of documenting extreme torment for the thrill of it, but uses that presentation to examine anxieties that shadow human experience. RL

23. Santa Sangre (1990. Dir: Alejandro Jodorowsky)

So much more than a horror film, but then Jodorowsky is so much more than a filmmaker. A dazzling, curious, mind-blowing cavalcade of images and sumptuous imaginative twists and turns. A magical take on the psycho-drama, sensitive and exploitative in equal measure. Young Fenix, aspirant circus child, witnesses the night his knife-thrower father cuts off the arms of his trapeze artist/religious nut mother, and he is never quite the same again. Jodorowsky’s son, Axel, plays the grown Fenix with an astounding sense of pathos and intensity, and the supporting cast move around the screen like a satanic inversion of a medieval mystery play. This is theatre, gothic and timeless, pulling in a multitude of horror traditions. There is no movie like Santa Sangre – it is a masterpiece of world cinema, not just of the horror genre. GR

24. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974. Dir: Tobe Hooper)

Pulled together on a relatively shoestring budget, the cultural impact of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre positions it as a foundational horror of the slasher subgenre, with echoes of the narrative and aesthetic possible to trace in swathes films made since. Sally (Marilyn Burns), her brother Franklin (Paul A. Partain), and their friends Jerry (Allen Danziger), Kirk (William Vail), and Pam (Terri McMinn) are on a road trip with a twist. After visiting Sally and Franklin’s grandfather’s grave, investigating reports of vandalism and desecration, they decide to also stop by their grandfather’s old house. It is here that things start to take a turn. They pick up a hitchhiker who becomes increasingly strange and violent before being forced from the van. They stop for gas, only to be told that the pumps are empty. They continue on but, unfortunately, stop by the home of a cannibalistic family to ask for gas. Big mistake. They are picked off one by one in sudden and brutal ways, with Sally emerging as the lone survivor. Though The Texas Chainsaw Massacre was marketed as being based on a true story, connections to factual events are mostly found through details rather than major plot points – the allusion to serial killer Ed Gein in Leatherface’s characterisation, for example. Often positioned as a key example of exploitation film due to its sadistic displays of violence towards female characters, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is nonetheless an archetypal slasher, exhibiting a key example of ‘final girl’ trope. RC

25. Eyes without a Face (1960. Dir: Georges Franju)

25. Eyes without a Face (1960. Dir: Georges Franju)

Eyes Without a Face (Les Yeux sans visage), directed by Georges Franju, explores fears of medical malpractice, invasive surgeries and our literal and emotional attachment to our faces in a disturbing Gothic narrative. Doctor Génessier (Pierre Brasseur) is believed to be grieving following the death of his daughter Christiane (Édith Scob), but the truth is much worse. Christiane has been disfigured in an accident and is hidden at their home in a mask until her father can perform a face transplant on an unsuspecting victim. The black and white cinematography complements the eeriness of the storyline and makes the surgery scenes look grimly plausible (whereas the additional scrutiny of full colour might have ruined the effect). Franju was told to avoid blood for fear of upsetting French censors which inadvertently makes the medical horror all the more unnervingly clinical. The film’s influence, on both French cinema and globally, has been considerable. John Carpenter has suggested that the use of the plain mask worn by Michael Myers in Halloween (1978) was inspired by Christiane. More recently, Pedro Almodóvar’s The Skin I Live In (2011) shares several similarities with Franju’s film. GS

26. The Cabin In The Woods (2012. Dir: Drew Goddard)

Many horror fans may have bipassed this film expecting it to be another in a long line of dull slashers, but this is perhaps the most truly original American horror film of the last twenty years. To give away it’s many twists and turns would be unforgivable to the uninitiated, but director Goddard and Buffy creator Joss Whedon’s witty, knowing script lays on the thrills, the good old fashioned laughs that some of the best party horror films always delivered, as well as the post-modernism we have come to expect from Whedon with his franchise hits, The Avengers and Age Of Ultron. GT

27. Starry Eyes (2014. Dir: Kevin Kolsch and Dennis Widmyer)

Possibly the most bucolic treatment any film-maker has ever given Hollywood, Starry Eyes is the horror cousin of Mullholland Drive and Ivan’s XTC, the extra ten yards of crazy from Maps to the Stars. Bold ambition, bitchiness and paralyising insecurities are matched with occultism, demonology and raw, brutal horror. Again, reminiscent of Naomi Watts’ career-defining turn in David Lynch’s Mullholland Drive, Alexandra Essoe’s stunning central performance is what makes the film so affecting. And when the blood-letting finally comes, there is no holding back. Brutal stuff. GR

28. Hereditary (2018. Dir: Ari Aster)

Annie Graham (Toni Collette) is a miniatures artist, living in Utah with husband Steve (Gabriel Byrne) and children Peter (Alex Wolff) and Charlie (Milly Shapiro). Annie creates dioramas of traumatic events, and of the family home. And it is here, as well as in the film’s title, that the most striking element of Hereditary’s brand of horror is foregrounded: all threat, intrigue, and terror in Ari Aster’s feature film directorial debut is inextricably linked with family and intergenerational anxieties. Hereditary traces the destabilisation of family life following the death of Annie’s mother. The home becomes haunted, not only by a malevolent exterior force, but also through the exposure of secrets and existing tensions in the events that shake familial foundations. Collette’s performance stands out in this film as a powerful portrayal of the rawness of grief and rage, as well as her grasps towards hopeful communication. Though (slight spoiler alert) Hereditary may not be particularly progressive in its suggestion that demonic power can only thrive when liberated from a female body, Aster’s use of familial and domestic life as a setting for the haunting and inheritance of trauma is nonetheless impactful. RC

29. The Happiness Of The Katakuris (2001. Dir: Takashi Miike)

The incredibly prolific director Miike has forged a career usurping genre expectations; first with yakuza gangster movies, like Fudoh: The Next Generation and the Dead Or Alive trilogy, then spectacularly with horror. Miike’s films cross genres and take unsuspected plot turns into fantasy, all of which adds to the disorientating horror. The Happiness Of The Katakuris largely avoids some of the more extreme imagery of his other horrors like Gozu, but still relishes in surreal visuals and, this time, musical numbers. Beautifully shot and realised, Miike’s vision come across like The Sound Of Music with zombies, yes, as good as that sounds! GT.

30. Ring (1998. Dir: Hideo Nakata)

Hideo Nakat’s Ring (1998) is often recognised for its influence on American horror, prompting a remake starring Naomi Watts in 2002 and a Western interest in J-Horror which also produced the US adaptation of Takashi Shimizu’s Ju-On: The Grudge (2002). The film’s global impact is a reflection of the universally unsettling elements of its central narrative. Journalist Reiko Asakawa (Nanako Matsushima) is told that her niece died as the result of a haunted videotape and decides to investigate. There are several innovative elements which provide the key to Ring’s enduring influence. Its use of technology as a source of quiet menace is inspired – particularly by making a blank television somehow terrifying – and it is precisely the mundanity of much of its imagery that adds to the sense of uncanniness within the film. Its focus on the power of the screen, encapsulated in a scene in which the cursed tape’s image is caught within Reiko’s pupil, is also a theme that gains more relevance with subsequent technological advancements. Ring is also unusual for its pace, which exchanges quick jump-frights for drawn-out anticipation. The tape’s victims spend several days waiting for retribution for watching and it is this tension that makes the film so memorably disturbing, as both characters and audience are made to stew in agonising suspense. GS

31. Alien (1977. Dir: Ridley Scott)

What could possibly be more terrifying than being trapped in an isolated location, hunted by a murderous assailant who is intent on killing you in any number of nasty ways? Answer. You play out this scenario in space, thirty-nine light years from Earth, and endow the bloodthirsty alien chasing you with two sets of jaws and a very unpleasant method of reproduction. Ridley Scott’s Alien is one of the most significant and innovative Horror films ever made, responsible for some of the most recognisable and celebrated iconography the genre has ever seen. Following the very basic principle of ‘slasher on a spaceship’, Scott overlays this outline with interplanetary degrees of atmosphere and bleak dread, creating an environment of intense, paralysing claustrophobia in the vast, dead wastelands of outer space. Dan O’Bannon’s screenplay fleshes out the lives and interpersonal dynamics of the unfortunate passengers of the Nostromo in great detail, while the H. R. Giger-designed Xenomorph has become an emblem of cinematic terror, expertly proficient at ripping the flesh off those same characters, and sending more than a chill or two down many a spine. Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley also put a new spin on the ‘final girl’ trope, sidestepping altogether questions of sexual purity or transgression to focus instead on her technical knowledge and self-sufficiency. The film impresses itself on your memory – everyone remembers watching *that* John Hurt scene for the first time – and gave Horror fans an entire new dimension of fear at which to shudder. RL

32. Dawn of the Dead (2004. Dir: Zack Snyder)

Controversial? I don’t think it is. Snyder’s remake of the great Romero satire updates in all the places it absolutely had to and hits the mark every single time. Zombies no longer amble, they come at you with a terrifying ferocity and pace. The movie has a modern sense of humour, a real attention to the nastiness that simply must be in a zombie movie, and a superb cast including Ving Rhames, a brilliant Sarah Polley (before she became one of the most interesting film-makers around), and a pre-Modern Family Ty Burrell enjoying his time as an unapologetic asshole. It doesn’t forget to be a satire on George Dubya’s America, either. A fabulous remake. GR

33. The Thing (1982. Dir: John Carpenter)

John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982) is an atmospheric and claustrophobic tale of American researchers trapped in an Antarctic base while a parasitic alien life form picks them off one-by-one. The eponymous ‘thing’ can imitate other humans, creating a sense of constant paranoia in the remaining crew members, but will eventually collapse into a pulsing mass of flesh, blood and viscera before attacking again. It is precisely these incredible special effects, designed primarily by Rob Bottin, which marked the film out as a significant landmark in horror and are still stomach-churning nearly four decades later. The Thing is an early example of special effects driven body horror which would become increasingly common in the 1980s, particularly in the work of David Cronenberg and Bryan Yuzna’s Society (1989). While its visual innovations cemented The Thing’s legacy, it is the effective utilisation of those special effects within an already gripping narrative that makes it particularly effective. The way the creature looks is not the only terrifying thing about it – it is also attacking, maiming and murdering for no discernible reason and it is this senseless destruction, combined with the permanent uncertainty that it provokes, which stays with the viewer almost as much as the flailing tentacles and spider-dogs. GS

34. The Company Of Wolves (1984. Dir: Neil Jordan)

Jordan’s film cleverly taps into the darkness that exists in many of the fairy tales read to us as children, but also has a good stab at reinventing the portmanteau horror film made popular by Amicus Studios in the sixties and seventies. Adapted by Jordan and Angela Carter, from her original short stories, the finished script has more in common with Carter’s 1980 radio adaptation. This traditional storytelling pervades the film and leads to a feeling of unbalance when mixed with the gory special effects: this is truly an adult fairy tale, one that only works because the terror remains in our subconscious since childhood. GT

35. Prevenge (2016. Dir: Alice Lowe)

35. Prevenge (2016. Dir: Alice Lowe)

It is common knowledge that pregnancy can provoke some odd cravings. These cravings, some speculate, are indicative of a nutritional need of the foetus, or the person carrying it. Prevenge, written, directed by, and also starring Alice Lowe, asks: what happens when you suspect that your baby might be prompting cravings for murderous vengeance? Ruth’s (Alice Lowe) husband was involved in a climbing accident where he was cut off from the rest of the group. Guided by her unborn baby, the heavily pregnant Ruth tracks down each person who elected to sacrifice her husband’s life for their own, and takes revenge. Though there are, of course, notable exceptions, mothers in horror typically fall into two camps: those who strive to defeat the monstrous outsider threatening their family, and those who are the obsessive, smothering, root cause of their offspring’s transgressions. The good mother and the bad mother. Prevenge on the other hand breaks away from these pole archetypes, and instead constructs a story much more complex in its thematic undertones and implications. This comedy slasher was also mostly filmed in Cardiff, so keep your eyes peeled for some familiar spots! RC

36. Switchblade Romance (2003 Dir: Alexandre Aja)

You’d been forgiven for thinking that Alexandre Aja’s unapologetically brutal slasher-on-steroids does very little to rethink or reimagine Horror tropes. Its delight in seeing human bodies intersected by sharp (and not-so-sharp) objects, with a loose-form plot of terrified (and mostly female) characters being pursued by a maniacal killer in an elaborately grim game of cat and mouse, clearly places it as a descendent of the brood of Slashers from the 70s and 80s such as Halloween, Friday the 13th, and (particularly) The Texas Chain Saw Massacre – the only difference being, perhaps, the twist in its narrative tail (itself a device that is hardly unknown to genre filmmakers). Yet its significance lies in being one of the first Horror films to be categorised as part of the New French Extremity ‘movement’, alongside Marina de Van’s brilliantly disturbing and heart-rending In My Skin from 2002. Both films helped to furnish the blood-splattered template for this renewed, intensified interest in body horror and the idea of the body-in-pain, which gave us such squirm-fests as Martyrs (2008), Inside (2007) and Frontier(s) (2007). Switchblade Romance serves up gore ‘n’ guts spectacle in buckets, whilst aiming to do something interesting with the idea of unreliable narrative perspective. Yet its greatest achievement will probably always lie in making this new wave of extreme European Horror palatable (as far as such a thing is possible). RL

37. It Follows (2014. Dir: David Robert Mitchell)

Part of the recent resurgence of the artful, thoughtful horror movie, Mitchell has found that gold nugget for horror auteurs: the priceless premise. Here we have a demon who takes any shape it needs to get close to you, and when it does it will rip you to pieces. You can outrun it, but you can’t shake it off. You can, however, pass it on. How? By having sex. Interpreted in a variety of different ways, including both as a satire on the abstinence movement and as poster campaign in that movement’s favour, It Follows is a striking, knowing horror movie, and in its lead, Maika Monroe, it produces a scream queen for the next generation. GR

38. Dr. Jekyll And Sister Hyde (1971. Dir: Roy Ward Baker)

Here it is! The greatest horror film about sexual identity and cross dressing ever made. This was Hammer’s third attempt at Robert Louis Stevenson’s classic novella and is contemporaneous to Amicus Studios own admirable adaptation, I, Monster, but this is the most delirious fun. The late, great Ralph Bates plays Dr. Henry Jekyll searching for the elixir of life by using female hormones from recently murdered women, reasoning that females live longer than males. But, guess what? That’s right, rather than turn him into a murderous animal, he is transformed into an absolutely captivating Martine Beswick. Throw in Burke and Hare, Jack the Ripper, and a good dose of classic early seventies Hammer Grand Guignol, and you have one of the most deliriously fun horrors Britain has produced. GT

39. Vampyr (1932. Dir: Carl Theodore Dreyer)

If you like your horror movies to move around you like a mist, then this is the film for you. Dreyer was one of the earliest geniuses to really understand cinema as an expressive artform rather than just a fantastical circus-ring. A great innovator (his 1928 masterpiece, The Passion of Jean d’Arc invented much of cinema’s language), he uses many tricks in Vampyr to tell the haunting tale of an ancient curse on a family home. Packed with iconic images and the famous dream sequence shot from inside a coffin, Vampyr has lost none of its power to impress and disturb. GR

40. Ginger Snaps (2000. Dir: John Fawcett)

Ginger Snaps is a cult Canadian horror which takes the werewolf movie, associated primarily with howling men shedding clothes, and transposes it onto the horrors of puberty and the experience of being a suburban teenage girl. Director John Fawcett brought co-writer Karen Walton on board partly by emphasing the need for better-written female characters in the genre and protagonists Brigitte and Ginger Fitzgerald are, in all of their awkward, moody and vicious eccentricities, certainly neither the sex objects nor meek heroines populating most teen horror films. When Ginger (Katharine Isabelle) is bitten by a werewolf it wreaks havoc on both her body and her relationship with Brigette (Emily Perkins), serving as an ideal metaphor for the painful transformations of puberty. Placing a complicated sisterly relationship filled with both devotion and despair at the centre of its narrative was, and still is, a novelty in the genre. The film continues to fuel debate as to whether it conforms to or subverts the ‘female body as monstrous’ trope, but the complex characterisation of both Ginger and Brigette, the excellent special effects and its focus on under-represented experiences nonetheless highlights that Ginger Snaps was a welcome intervention in both body and teen horror films, constructing a link between the two which had not existed before. GS

41. The Blair Witch Project (1999. Dir: Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez)

The Blair Witch Project is a supernatural horror film renowned for reviving the ‘found-footage’ technique, further popularised by more recent films such as the Paranormal Activity franchise (2007-), Cloverfield (2008), and As Above So Below (2014). The characters in The Blair Witch Project, Heather Donahue, Michael C. Williams, and Joshua Leonard, were named after the actors who played them. Additionally, the actors and the characters they played shared their vocation as student filmmakers. Taken alone and together, these strategies further blur the boundary between film and reality foregrounded by the found-footage technique – a displacement heavily utilised by the marketing around the film’s release. In 1994, Heather, Mike, and Josh travel to Burkittsville, Maryland, to make a documentary about the Blair Witch. After interviewing local residents about the legend, the trio become lost in the woods. Bonds weaken as the cyclical terror of their wanderings begins to grow, heightened further by the unnerving sounds around them, and the strange symbols that they discover. At the film’s close, it is unclear what actually happens to Heather, Mike, and Josh. What is clear, however, is the impact that The Blair Witch Project has had on the found-footage subgenre, and horror more broadly. RC

42. Possession (1981. Dir: Andrzej Zulawski)

There is no film like Possession in the history of cinema, let alone on this list. A fierce, fast and swirling attack of the politics of East Germany, the early set up of some unravelling espionage thriller soon is consumed by a bizarre impressionistic painting cast in greys and cold blues, detached scrolls of monologues and violence, and, of course, some kind of unfurling slug alien that lives in the apartment upstairs. Sam Neil does a hearty job with what must have been a dizzying script and set, but it is Isabelle Adjiani who steals the show. Her famous scene of breakdown in the subway, where she appears to be collapsing from the inside, miscarrying whatever it is that is possessing her, is a searing, unforgettable moment that even in isolation carries with it a blistering shock. To really understand the film you might need to dedicate a PhD thesis to it, but to watch it, to experience it, evokes neither an analytic nor academic response. This film, if you have not seen it before, will blow you away. GR

43. Under The Skin (2013. Dir: Jonathan Glazer)

Perhaps the hardest film to categorize on our whole list, Glazer’s art house science fiction horror film is a stunning achievement and a completely unique filmic experience. Hollywood superstar Scarlett Johansson roams Glasgow looking for men to seduce and absorb into a black void, presumably feeding on them in some way, either their physical or spiritual presence or both. The visual ability Glazer displayed in music videos for the likes of Massive Attack and Radiohead is here in abundance, and the lack of traditional narrative is similar to a music video’s narrative. Johansson is superb as the seductive alien, both cold and callous as well as welcoming and friendly, and it’s surreal seeing her in such a typically cold British film. In fact, Glazer’s visuals and tone are very reminiscent of a bygone age of British horror and the video nasties era, where it was clear the unpleasant tone of certain films were offending the sensibilities of the BBFC. Challenging, uncompromising, original, and immersive. Take the plunge into the void. GT

44. The Neon Demon (2016. Dir: Nicolas Winding Refn)

Worlds away from creaky haunted houses, cabins, and cemeteries, The Neon Demon’s depiction of sex, death, and body horror leaps out from its glossy high fashion façade. The filmic narrative follows aspiring model Jesse (Elle Fanning), as she moves from Georgia to Los Angeles following the death of her parents. As a child, Jesse used to think of the moon as a huge, round eye, questioning whether or not it could see her. Carrying on this thread of natural imagery, she is asked by a fellow model: ‘What’s it feel like to walk into a room and it’s like the middle of winter, you’re the sun?’. ‘It’s everything’, Jesse replies. Unlike the models who have undergone surgery in their reach towards the ideals of contemporary femininity, Jesse is praised for her natural look. As Jesse’s career takes off, she becomes subjected to scrutiny and jealousy from those around her, leading to grotesque consequences. To be seen is everything. To be beautiful is everything. Like Jennifer’s Body and Raw, The Neon Demon is a film concerned with the various meanings hovering around notions of consumption. What sets the film out as generically distinctive, however, is its aesthetic, replete with the intense colour palette that characterises much of Refn’s filmography. RC

45. The Evil Dead (1981. Dir: Sam Raimi)

Horror-Comedy is the most difficult genre combination to get just right. Not only do you have to make people scream, you’ve also got to make them laugh, sometimes during the same scene – and no films fall quite so flat as unfunny comedies or a terror-free scary movies. Sam Raimi’s 1981 commercial debut The Evil Dead is an example of how to strike this balance perfectly. The film follows a group of university friends on a holiday trip to a cabin in the woods in rural Tennessee, which takes a turn for the nightmarish when they unearth a book of the dead in the cellar, unleashing a demonic force which dispatches the gang one member at a time. The film’s practical, in-camera special effects – ranging from fake blood to stop-motion animation – lend the Horror elements a tactile quality that emphasises the gruesomeness, but also play to the over-the-top luridness that complements the darkly comic tone and slapstick set-pieces. This balance is also a testament to the actors – particularly Bruce Campbell’s now-iconic role as Ash Williams – and their commitment to a production that was, by all accounts, a fairly torturous process. Raimi revisited his horror-comedy hybrid with two further instalments, boasting bigger budgets and sleeker visuals, but lacking the rough-edged charm that makes The Evil Dead a paradigmatic genre film. Not only did he popularise the ‘cabin in the woods’ trope that has influenced countless directors, but he demonstrated what Horror-Comedy could achieve with an ambitious idea, the right script, and a whole lot of red-dyed corn syrup. RL

46. Brain Dead (1992. Dir: Peter Jackson)

Years before his massive success with The Lord Of The Rings movies, Peter Jackson made some truly mind blowing gore movies and this is the best of the bunch. After being bitten by a rabid Sumatran rat-monkey, Lionel’s mum starts to get sick and dies only to return as a flesh-hungry zombie monster. With wit to spare, outrageous gory effects, and some fever pitch performances, Brain Dead even finds time for a genuinely touching romance. And there’s a zombie baby! Jackson here revels in his clear love of horror and comedy and it makes you wonder if he made the right decision going to Hollywood… sort of. GT

47. Vampyres: The Daughters of Dracula (1974. Dir: José Ramón Larraz)

In many ways Vampyres is an odd little film, riddled with loose ends and seemingly superfluous characters and scenes; but it is a film that is tied together by its final moments and by the glut of potential interpretations the final few lines spins out. In this sense Vampyres can be a richly rewarding or deeply frustrating movie, depending on whether it clicks with you or not (it certainly clicked with me). But apart from that, Larraz’s movie is an extremely affecting dreamscape, eerily shot, and acted with a surprising amount of conviction. Marianne Morris fights her way amiably through some pretty terrible dialogue as the alpha female of the vampiric lesbian duo stalking the English countryside for victims, while Playboy centrefold Anulka is extremely good as the younger more feral creature of the night. It is quiet vicious, quite earthy, and has no light at the end of it, unless you decide eternal vampirism in a dilapidated mansion with the woman you love is a happy ending. GR

48. Society (1989. Dir: Brian Yuzna)

A prolific producer of, among other cult items, Stuart Gordon’s classics Re-Animator and From Beyond, Yuzna made his directorial debut with this body horror classic. For the most part it deals with the horror of paranoia and the underlying unease of perfect suburban America in a similar way to David Lynch. The paranoia increases as the film progresses to the finale which is a joyous gooey orgy of violence and madness all made possible by special effects wizard Screaming Mad George. Often considered a minor entry in the body horror stakes, this writer for one believes it to be the best example of body horror working with a fascinating narrative. GT

49. Scare Me (2020. Dir: Josh Ruben)

The most recent film on this list, and it’s nice to see horror films can still innovate after such a long time flitting between the rigours of genre tropes and the upending of expectations. Josh Ruben’s spooky little lockdown horror-farce is most memorable for its use of the storytelling tradition. Ruben writes, directs, and stars, and he’s very good in all three departments, but the film belongs largely to the dazzling Aya Cash, who struts her stuff as best-selling horror novelist Fanny Addie, trapped in a stormy remote cabin with Ruben’s struggling writer Fred. They decide to pass the night by telling each other scary stories, and each story is performed without much need for special effects. It’s all mood and imagination, and it works. This is where scary stories began, back when Grendel was terrorising townsfolk. It wouldn’t work with a sharp script, fabulous performances, and good direction. Turn off the lights, light a fire, pull up a blanket. This is old school, and a lot of fun. GR

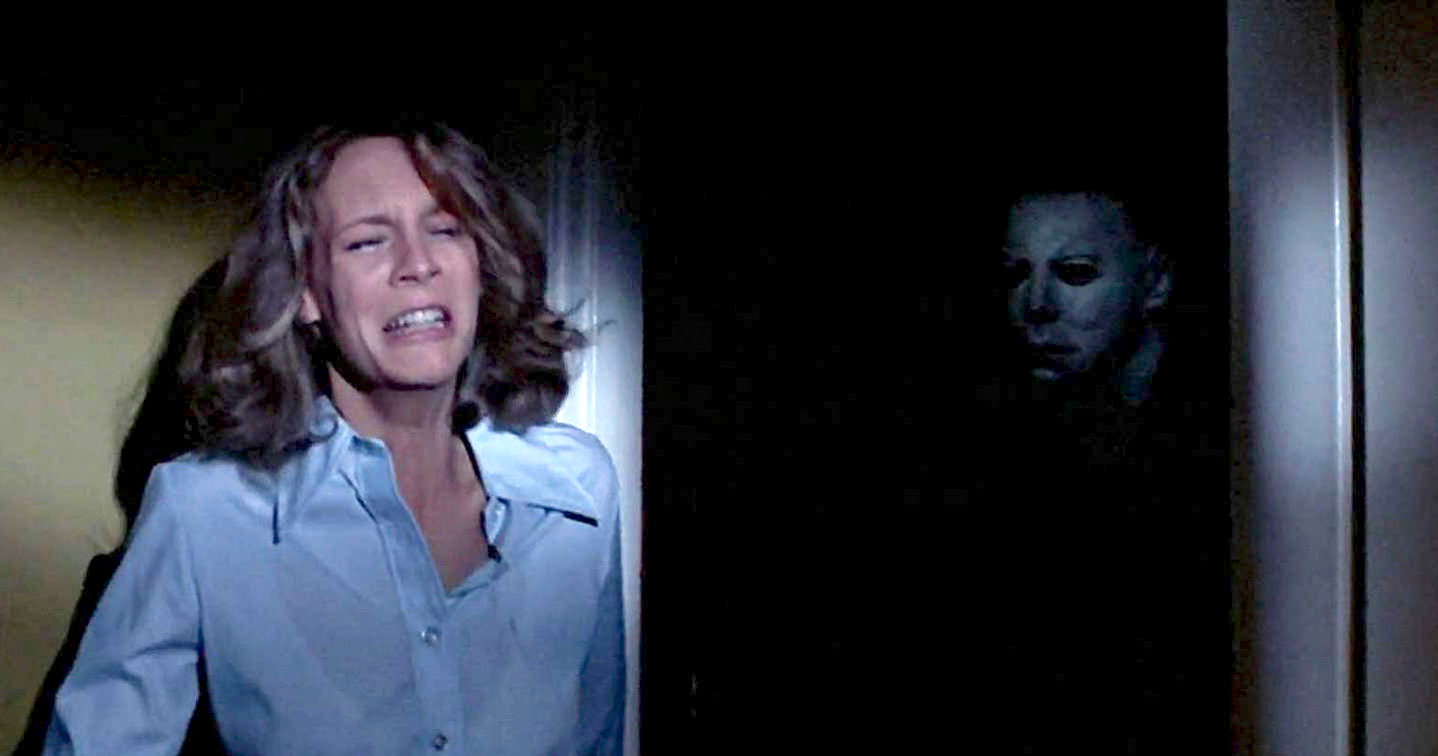

50. Halloween (1978. Dir: John Carpenter)

It’s easy to forget how influential and innovative this film was and remains. Okay, so it draws on the masked knife-man of the Italian Giallo slashers of the 1970s, but by transferring the horror to suburban America, Carpenter tapped into part of the national psyche in a way that meant horror films would never be the same again. It changed everything about the way the American indy system – and soon the studios, too – viewed horror, and it’s a perspective that remains today. Halloween made American horror a numbers game – body count, box office, and sequels. The landscape of horror (and, dammit, the experience of being a teenager who’s into movies) would be very different nowadays without this perfect film. GR

Wales Arts Review is home to a number of horror-related articles.

The 50 Most Innovative Horror Films was originally published in Wales Arts Review in 2020.