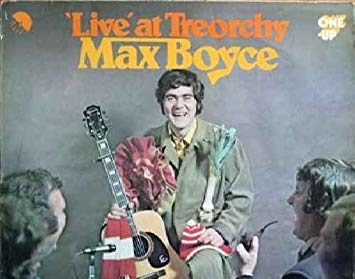

2022 marks ten years since the launch of Wales Arts Review, and as part of our celebrations, throughout this year we’ll be revisiting some of the best and most loved features, interviews, and reviews from our archive of nearly five thousand published pieces. Today, we look back to our series of spotlights on the great albums by Welsh artists and Darren Chetty’s love letter to the iconic record, Max Boyce’s classic, Live at Treorchy.

At my primary school in Swansea in the 1970s, we would sometimes have ‘Costume Days’, which were taken very seriously indeed. Kids would dress up, parents would showcase their creative skills and teachers would judge. It was serious competition. 40 years later, there are three costumes I vividly recall. One was a child dressed as Starsky and Hutch (picture a child’s head in a rabbit hutch surrounded by stars and a key – see, serious). Another was Evel Knieval – a boy in a white jumpsuit with stars and stripes trim, made by his mother who was streets ahead of the other parents when it came to using a sewing machine. The third costume required neither cryptic crossword skills nor tailoring skills – just a red and white scarf, a curly wig and a paper leek as tall as the child struggling to hold it up.

In South Wales in the late 1970s, this all made sense. Max Boyce was as much of an icon as any cop show or daredevil with a death drive. And just as it seemed as though every child on my street had the wind-him-up-and-watch-him-go Evel Knieval action figure and the replica Starsky and Hutch car, everyone’s parents owned a copy of Max Boyce Live at Treorchy.

Everyone’s, that is, except mine. My mother and father were from overseas and had arrived in Wales a few years before my birth. I was the first person in the entire history of my family to be born in Wales. And, more than anyone else – with the possible exception of Mr Roberts who led the Saint David’s Day Eisteddfod rehearsals at school – it was Max Boyce who taught me what it meant to be Welsh. As I listen again to the first of four of Max’s albums to go gold, I can’t help but try to discern what exactly it was I was learning.

Live at Treorchy was Max’s flawed magnum opus. Even the flaws fascinate me. Do they too reveal something about Welshness in the 1970s? Whilst he already had two albums under his belt the story goes that he struggled to sell 50p tickets for his recording at Treorchy Rugby Club and ended up having to give them away. Yet you wouldn’t guess this from listening to the album, recorded in one take in 1973. From the opening ‘Oggys’, we hear a man who is at one with his surroundings. It is as though the funniest, most popular bloke in the pub has been given a microphone.

“Boys, I’ve come home!” he says, before affectionately mocking the venue. ‘What do you think of it?’ I said, ‘It’ll be nice when it’s finished.’ ‘That’s not the airing cupboard’, he said, ‘that’s the lounge.’ ‘Have you seen Treorchy play this season?’ ‘No’ ‘Why’s that?’ ‘They don’t come to see me when I’m bad.’

Max proceeds to share an anecdote about performing as a child at the Eisteddfod in front of his whole family, forgetting the poem and his mother pretending not to know him. It may be true, it may not be – it’s not until side two of the album that we begin to get to know much about Max. Side one reveals that he is a Welsh speaker (able to switch quickly between Welsh and English so that people like me don’t miss a joke) and that he really, really likes rugby.

I learnt about the importance of rugby to Welsh people from Max. For my father, born in South Africa and classified as Indian under the Apartheid regime, rugby was the game of the oppressors. At the English university I attended, it was the game of the posh boys. But in Wales it seemed was the game of The People. Or at least it seemed like that on TV. At school, we cared more about football than rugby – and to this day Swansea City averages about double the crowds of The Ospreys with whom they share aground. But international matches are something else. And whilst Swansea University Professor Owen Sheers may well be the first Welsh Rugby Union poet-in-residence, in the 1970s Max held that title in all but name. A whopping six of the nine songs on Live At Treorchy are about rugby.

“9-3” celebrates Llanelli’s historic win over New Zealand’s All Blacks in 1972.

But we all had doctors papers

And they said just the same

That we all had Scarlett fever

And we caught it at the game.

The first line would inspire the title of Max’s follow-up album that went to number one in the UK album chart.

“The Scottish Trip” is the first of two songs to derive humour from the need to urinate after consuming a large quantity of beer. Listening now, this sounds like a joke being spread very thin. It may have sounded like that at the time of its release, but as a kid, this was the most grown-up listening I encountered until my older brother brought home poor quality tapes of the Sex Pistols. Indeed many of the playgrounds jokes my brother brought home from school were, I later discovered, reworked Max Boyce gags. We even sang Max Boyce at school, but with bowdlerised lyrics (our version had no mention of gambling, beer and fags, or Soho sex workers). The cover of Live at Treorchy shows an audience with beers on the table. Someone is smoking a pipe. Yet listening again, I realise there isn’t a swear word on the album.

“The Ballad of Morgan The Moon” is Max’s most surreal offering. “Some may argue that the Americans were the first on the moon, but no lads they were the first to get a man on the moon and bring him back. I had a postcard from him. It said, ‘It is Cheese. And in brackets – Caerphilly.’”

The high point of this one comes at the end. The band stop playing so Max can fully showcase his wordplay.

He landed like linen – lovely line that

He landed like linen

On a crusty old crater

Dai said he’d get there – lunar or later

There is something about the alliteration, the interrupting of the poem for a self-congratulatory comment and then the delight in ending with a pun that receives as many groans as laughs that particularly pleases me. I can almost see Max winking as he delivers it.

In “The Outside-Half Factory”, Max combines valley industry with rugby to eulogise Welsh number 10s. Barry John would reciprocate a few years later, describing Max as Wales’s ‘greatest entertainer’ in his introduction to Max Boyce: His Songs and Poems. 20-odd years later Cerys Matthews would sing that every day, when she wakes up, she thanks the lord she’s Welsh. In “The Outside-Half Factory”, Max informs us that Jesus Christ himself is Welsh. By this point in the album, I’m pretty sold on the idea of Welshness as personified by Max. But then things take a dramatic turn for the worse.

Max re-appears on stage after the break to the sound of The Oriental Riff, a short melody created in the West and used as a trope for all-things East Asian (think Carl Douglas’ Kung Fu Fighting). And further stereotypes come thick and fast. You may have seen the recent footage of 15,000 Japanese fans giving perfect renditions of “Calon Lân” and “Mae Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau” to welcome the Wales team and staff to the Rugby World Cup. Watching these, I couldn’t help but think of Max’s “Asso Asso Yogoshi” story of the Japanese team that toured Wales for the first time in 1973. The song gets most of its laughs from Max’s cod-Japanese accent. A 2016 Wales Online article states that ‘Boyce is the first to concede that the way the song is constructed would be unacceptable these days.’ Yes, right. But the song seemed odd to me even as a kid – why do Max and his audience seem to find Japanese people so funny? The caricatures that accompany the lyrics in I Was There, the second of Max’s three books, do not help anyone who wishes to deny that the song was, is and always will be, rooted in racism. And I notice that a line from “Hymns and Arias” where Max puts on a South Asian accent in order to get a laugh has been cut from the 2005 The Very Best of Max Boyce version. (The line is included in a video I’ve seen of Max’s tribute band Boyce Zone but thankfully without any of them attempting an accent.) The Welshness on display suddenly seems less inviting. I’m mindful that this kind of humour was far from unusual throughout Britain in the early ‘70s. But then I also reflect that the only time I’ve encountered racial abuse on the street in the last decade has been on visits back to Swansea. And that even recent writing published and then retracted by Wales Arts Review, suggests there is a way to go when it comes to racism.

And it is still hard for me to comprehend that such lazy, unimaginative writing gives way to the song that I think justifies the inclusion of Live at Treorchy in any list of great Welsh albums. As the laughter from another joke about Treorchy Rugby Club subsides, Max introduces “Duw It’s Hard”. In the intro his voice changes from the ‘Oggy, Oggy, Oggy’ funniest bloke in the pub tone to one more personal and tender.

“Having worked underground for nearly eight years, I feel that I qualify to sing this song,” he told us.

They came down here from England

Because our output’s low

Briefcases full of bank clerksThat had not never been below

‘Cause it’s hard

Duw it’s hard

It’s harder than they will ever knowAnd it’s they must take the blame

The price of coal’s the same,

But the pithead bath is a supermarket now.

That line ‘it’s harder than they will ever know’ gives me shivers. In his book Wales Since 1939, Historian Martin Johnes describes “Duw, It’s Hard” as “a song as important to Welsh culture as anything written by Dylan Thomas or Saunders Lewis”. From John, I learn that Max was criticised for sentimentalism and fatalism. Indeed, it’s not political anger that’s driving the song, but nor is it resignation. Fundamentally, I think it’s best understood as a Welsh Blues lamenting a life where one faces a choice between life-risking labour that bears the consolation of humour and camaraderie and a safe but meaningless job. Max sings of how decisions are made about working-class people’s lives by people who lack even the desire to understand those lives. He doesn’t offer sloganeering solutions but rather articulates the sadness and the grief. Knowing that Max’s father died in a mining accident before his son was born gives the song added poignancy and suggests that Max knew “the laughter midst the fear” all too well. Somewhat belatedly, it strikes me that for Max “I know cos I was there” is more than just a catchphrase.

In “Ten Thousand Instant Christians” Max explores how the focal point of the community in South Wales is in transition; the church hymns are now sung, half-remembered, in the pub and at Cardiff Arms Park, but fewer people sing them in church. Here, rugby as the Welsh religion is viewed as a loss rather than a cause for celebration – but with a lightness of touch. Max ends the song, imagining Calfaria “now a bingo hall”; and indeed Calfaria Baptist churches in Aberdare and Llanelli to name just two have since closed their doors.

“Did You Understand?” is a mournful reflection on the National Coal Strike of 1972. Backed only by piano, Max again manages to communicate support for miners without glorifying mining. After a build-up of banter and five funny songs with some highly questionable lyrics, we have just been treated to a suite of three songs that highlight Max’s skill and sensitivity as a songwriter and a poet. Not only that, the Welshness and the masculinity set up in the first part of the show (where women feature only as wives men have to keep happy in order to go to rugby matches), has started to become more complicated, more nuanced and altogether more interesting. Are these just different facets of Max? Or did he believe he needed all that banter before he could reveal a sensitive side? And if so, was he right?

“Oggy Oggy Oggy!”

Max the comedian is back. A quick verse about Wales rugby legend and miner Dai Morris comes at the request of the audience. Then it’s on to the song with which Max will forever be associated. The audience already loves the song – “Heard it before have you?” quips Max in response to laughs ahead of a punchline. “Hymns And Arias” appeared on an earlier album, Max Boyce in Session but his rendition on Live At Treorchy is the sound of a man singing himself into the Welsh canon alongside songs like “Calon Lân”, “Cwm Rhondda”, “Delilah”, “Ar Hyd Yr Nos” and “Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau” – all of which are name-checked in the song. Over forty years later, it can still be heard at all rugby internationals. Since the early 2000s, it is also sung by Swansea City fans. Max performed a special version for the last ever league match at The Vetch Field. I know, ‘cos I was there.

Despite the four gold albums and “Hymns and Arias” becoming a terrace anthem, I’m not sure Max always gets the credit he deserves in Wales – at least in some quarters. Asking Welsh friends what they thought of Max, I encountered some nostalgia but also a fair deal of embarrassment. One person went as far as to suggest he was “basically a Welsh Bernard Manning.” When comedian Elis James was told on Twitter that he is the new Max Boyce, his response wasn’t one of extreme gratitude but rather “when I start buying oversized leeks you have my permission to shoot me.” All the controversy surrounding the 2004 100 Welsh Heroes list was whether or not nationalists had fixed it for Owain Glyndŵr to come first, ahead of Aneurin Bevan. But there was no public outcry about Max’s omission from the list. At least when 13th placed Catherine Zeta-Jones won an Oscar the year before, she celebrated with a cry of “Oggy, Oggy, Oggy”. Max Boyce: a Welsh Hero’s Welsh Hero.

A picture of Wales and Welshness (perhaps more accurately South Welshness) emerges in Live At Treorchy. It’s one of the men mostly; men drinking, and singing, and getting one over on the English. (Ironically, the mockery of Asian people seems to rest on a historically British sense of superiority). It’s one of a Wales in a time of uncertainty; the stability of the church and the mining industry is under threat and Wales winning their next rugby match is the closest thing we have to any certainty. Perhaps the whole of Live at Treorchy can be summed up by that line in “Duw It’s Hard”, “the laughing midst the fear.”

There’s a theory that Max’s success in Wales and beyond was largely due to the phenomenal Welsh rugby teams of the 1970s. In that decade, Wales won the Five Nations seven times, completing the Grand Slam three times. In players like Barry John, Gareth Edwards, Phil Bennett, JPR Williams, Dai Morris and Mervyn Davies, Max was not short of inspiration. But when I listen again to “Duw It’s Hard”, and “Did You Understand” I can’t help but wonder if the success of the Wales rugby team inadvertently robbed us of a poet. What if Wales had not had such great teams in that period? Surely Max couldn’t have sustained a career writing about Wales battling to avoid the wooden spoon each year. Where might he have focused his huge talent for songwriting and poetry instead?

Max Boyce Live at Treorchy: Darren Chetty was born in Swansea and lives in London. He is currently co-editing a collection of essays by Welsh writers. He tweets @rapclassroom.

For other articles included in this collection, go here: The Greatest Welsh Album.