Following the death of writer, artist and painter George Brinley Evans at the age of 96, Emma Schofield reflects on an extraordinary life and career.

Aged just fourteen years old and already working in Banwen Colliery, a career as an artist and writer was likely a long way from the mind of the young George Brinley Evans and yet, some sixty years later and already well into his seventies, Evans published his first book, Boys of Gold. A lot had happened in the intervening decades – a stint in the army, serving in Burma during World War II, before a return to working as a miner in Banwen Colliery. There were high points, such as his marriage to Peggy Jones, with whom he went on to raise a family, and there were low points, including an incident which led to him losing an eye in a mining accident.

As they so often do, the high and low points collided to provide a rich tapestry of experience from which to forge a new career in the wake of his accident. While recuperating following the loss of his eye, Evans was encouraged by his wife to begin writing about his experiences. An early attempt at writing TV scripts ultimately ground to a halt when Evans was advised to move to London in order to pursue his career, something he was unwilling to agree to. At the time Evans was raising his family in Banwen, determined to bring them up in the village in which he himself had been born and which he had always considered to be his home, reluctant to relinquish that connection, even in exchange for the chance of a whole new career.

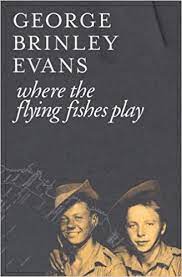

Several decades later and Evans, by now a widower, had become an accomplished short  story writer, studying under the guidance of tutors including Alun Richards. In 1998 he appeared alongside a host of new and established Welsh writers in Parthian Books’ Mama’s Baby (Papa’s Maybe) anthology, following it up with his own collection of short stories in Boys of Gold in 2000. The success of this first collection led to the publication of Where the Flying Fishes Play in 2006, inspired by his time serving in Burma, and was followed by When I Came Home in 2012, a reflection on the challenges of returning home after that time spent in the Far East. His writing was honest and heartfelt, with a focus on the people and sights which had left an imprint on his own life.

story writer, studying under the guidance of tutors including Alun Richards. In 1998 he appeared alongside a host of new and established Welsh writers in Parthian Books’ Mama’s Baby (Papa’s Maybe) anthology, following it up with his own collection of short stories in Boys of Gold in 2000. The success of this first collection led to the publication of Where the Flying Fishes Play in 2006, inspired by his time serving in Burma, and was followed by When I Came Home in 2012, a reflection on the challenges of returning home after that time spent in the Far East. His writing was honest and heartfelt, with a focus on the people and sights which had left an imprint on his own life.

In between, and alongside, the writing, there was the painting and sculpting. Evans’ artwork eventually found fitting homes within Big Pit and the South Wales Miners’ Library, as well as in the National Museum. Like his writing, his sculptures reflect his belief in the importance of the everyday lives of the people he had met and worked with over the years; his sculptures featured images of his fellow colliers at work in difficult, and often dangerous, mining conditions. His watercolours similarly depicted the scenes which Evans knew so well and had typically understated origins. Displaying a collection of his work as part of their ‘Images of Industry’ exhibition, the National Museum Wales referred to Evans’ use of everyday materials within his work, noting that the “material he most often used was household emulsion and watercolour on cheap paper”, with his sculptures created using “cheap and alternative material – a wire armature is covered in layers of old nylon stockings soaked in plaster, which is then teased into shape and sprayed with car paint”. A simplistic approach, which belies the complexity and emotion etched into the images and figurines crafted by Evans.

In spite of this late burst of creative success, Evans remained modest about his work and fiercely loyal to the village he loved so much. In an interview with The Western Mail in 2007, he described himself as someone who “just wanted to tell a story, a story about ordinary people who did what they were told and lived normal lives”. There are, arguably, few whose normal lives were quite so extraordinary and even fewer who could have told those stories with such good humour and warmness of spirit.

George Brinley Evans, 1925-2022.

*Featured image – Photograph by Kathy DeWitt, Hay Festival 2001, Alun Richards, Dai Smith and George Brinley Evans.