What literature influence Roald Dahl? In our latest collaboration with the Roald Dahl conference of Cardiff University, Claudia Lanza explores the relationship between one of Roald Dahl’s most mischievous works, his version of Cinderella from his collection of poetic reworkings of classic fairy tales, The Revolting Rhymes, and the various source materials, and asks what role the translator plays in the reinterpretation of the classics.

In 1982, when Roald Dahl wrote Revolting Rhymes, he created a work of re-writing, but the innovative thing is that he did it using the nursery rhyme form that gave each story a feature much more desecrating and sarcastic. What comes out from his recreations is a new way of considering the perfect moral characters of the past tales, and specifically he mocks, them subverting their actions, and making them, of course, revolting.

The sources of inspiration useful to Roald Dahl in order to rewrite the fairy tale of Cinderella would have been Perrault, the Grimm Brothers and Walt Disney. Each one of them in turn represents a new interpretation of the story, with the differences in the symbolic way of portraying morality, punishment, magic and purpose.

In 1697, Perrault wrote Cinderella as a simple form of entertainment for French cultural gatherings. He was followed later on by the Grimm Brothers who gave it a more patriotic interpretation. And last was the Walt Disney animated feature film of 1950 that created the visual features that are still in vogue today. In the Grimm’s version, animals substitute the figure of the Fairy God Mother (who is present in Perrault and transforms the animals). The time limit and the shoe are different, as well as the finale: in the French version Cendrillon forgives the two step-sisters allowing them to live in the court, while in German version the doves pull the sister’s eyes out as a form of punishment for having been mean. Tellingly, it is the Grimm’s version Dahl has sympathy with and follows, with the beheading of the step-sisters in his version.

In 1697, Perrault wrote Cinderella as a simple form of entertainment for French cultural gatherings. He was followed later on by the Grimm Brothers who gave it a more patriotic interpretation. And last was the Walt Disney animated feature film of 1950 that created the visual features that are still in vogue today. In the Grimm’s version, animals substitute the figure of the Fairy God Mother (who is present in Perrault and transforms the animals). The time limit and the shoe are different, as well as the finale: in the French version Cendrillon forgives the two step-sisters allowing them to live in the court, while in German version the doves pull the sister’s eyes out as a form of punishment for having been mean. Tellingly, it is the Grimm’s version Dahl has sympathy with and follows, with the beheading of the step-sisters in his version.

It seems at every opportunity Dahl opts for the darker side of the stories. It is obvious from cover; Quentin Blake‘s stark illustration is highly representative: two children scared, held by a wolf, an odd situation that puts the viewer exactly alongside the perspective with which we should read the entire collection. Everyone would be astonished, like the children, by seeing their own babies held by the villain of the stories. We could even consider the wolf as Dahl himself, the anti-storyteller who wants to deliver another side of the stories we have heard from the mouths of our parents.

Cinderella is the first story that opens this collection of revolting subversions. Almost everything in the story has changed: firstly the name of the orphan girl; not anymore Cinderella, but Cindy (a contracted and modernised version of the name). The desires Cindy expresses to her Fairy Godmother are a good example of current times and of the transformation made on the honest traits that usually are linked to her: she strongly wants a dress, a coach, a diamond brooch and the place of the balls are at the disco. She’s not a humble and defenceless girl as we remember. She’s been confined to a basement while mice eat her foot, no longer the charitable animals that help her.

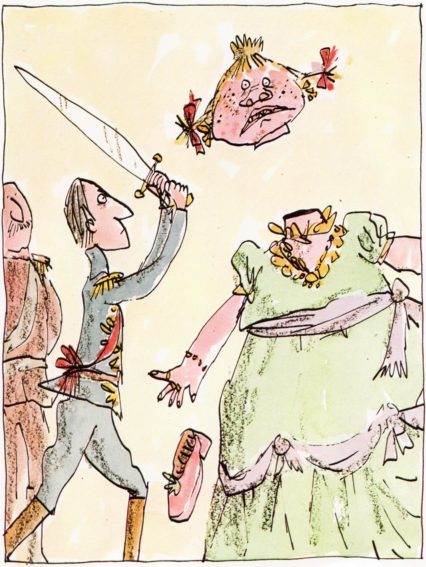

The darker side of Cinderella, as we have seen, comes from the Grimm’s version. The mutilation has been taken up by Dahl with the beheading of both step-sisters, and here it is an action that sees a change of mind in Cindy and wish for a life with a decent man, one that turns out to be a marmalade maker. In this way, we do have a repentance of sorts, an instructive ending for the audience, but not before Dahl has presented a subverted order of characters behaviour against the ethical values so precious for the traditional standards.

Roberto Piumini, the author who translated Revolting Rhymes into Italian writes on the art of translation:

Translating is considered by André Lefevere, a linguist and a key expert in translation studies, as a rewriting tool. Specifically, he refers to the term “refraction” (1992, in M. Ulrych 1997:237), that is not a reflection of different linguistic patterns into texts, but is a form of re-creation made by the translator to show the change in the perception of cultures. Believing that cultures are different, A. Lefevere is strongly convinced that in translating the texts that belong to them, the translator works as a literary manipulator who is able to transfer the linguistic and cultural patterns of that source culture to another one, the target culture, wearing the standards of the arrival audience.

In other words, translation is a form of rewriting adjusted for a particular ideology, and it is for this reason that translator can be seen as a second writer who is able to re-create the intention of the original author through other linguistic and cultural tools.

In 1995, another influential personality in the world of translation studies gave his own perspective on the work of the translator. Lawrence Venuti’s work The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation has been a source of inspiration for a future generation in considering the role of translator. From his point of view,

the translator can choose to make his presence visible or invisible, for this reason he created two terms: domestication and foreignization. In the first one, the translator goes along the target culture standards, writing focused and acceptable translations in contexts different from the original; while the second strategy is used when the translator wants to keep the linguistic and cultural elements of the source texts, even if the reader could face problems and difficulties in interpreting them. What is crucial in translation studies is to be able to deliver the same intention of the original author, keeping that idea of functional equivalence between texts.

A version like the one realised by Roald Dahl, a rewriting by rhyme with a AABB scheme, is very hard to manage, also having to do with a text full of extreme actions and ingenious game of words. Many are the alterations he did. Starting by adding some phrases or eliminating part of verses, substituting some of the punctuation forms more suitable for the target language that is very different from English in the way it guides the reader’s orientation into the texts putting, for example, sequences of guidelines that link the overall significance. The Italian translation of Revolting Rhymes is titled Versi Perversi where “perversi” (literally: perverse) has been preferred by the author as a translation useful to create the rhyme with “versi” (verses), a pattern that he has followed during all his translation to deliver the same feeling as the source text.

From the beginning of Cinderella’s rhyme, Piumini changes some aspects in order to keep that rhythmic feeling of the original tale. The opening begins with a warning written by Roald Dahl to his readers, concerning fake beliefs developed during years of good tradition that has sweetened children with ethical thoughts. He promptly uses very strong language: Cindy is in a “slimy cellar” while the rats that are “eating her foot”. Piumini makes important alterations, in particular he completely changes the first verse with ‘…E la sposò, e lei visse contenta’. Eh no! La vera storia fu più cruenta.’ [And he married her and she lives happily ever after. Well, no! The real story was much more gory]. So, instead of translating story with the Italian correspondent storia, Piumini choses a complete different sentence that ends with contenta (happily) in order to create the AABB scheme with gory (cruenta) and to keep the sarcastic feeling of presenting the other side of reality as realised by Dahl.

In the middle of the Dahl version of Cinderella we are at the ball; here it is used in a very colloquial way of writing and Piumini creates the same impression, standardising the text with the linguistic features of the Italian, often adding some words to guide people accustomed to other versions. He also inverts the order of the words, a way of translating that fits the needs of the Italian readership and the creation of AABB rhyme scheme.

In the final part we can see how the moral and perfect figure of Prince Charming has been subverted: he orders a beheading. Here Piumini eliminates the word slut, translated as pezzente (tramp). The reason has to do with the educational way of thinking in Italy that all the bad words have to be cut off by literal text as well as useless repetition that in English are important to create emphasis.

The result obtained by Piumini emerges to be an equivalent translation realised by standardisation techniques. However, the intention of letting children free from the moral stories of the past has been maintained in the Italian version, as well as at the same time overcoming the ancient features related to the characters. Parody is an important tool that enabled Dahl to succeed in this work of subversion and Piumini has been loyal to this way of interpreting reality and exploring the world of imagination beyond the boundaries of classical nature.

You might also like…

Celebrating 100 years of Roald Dahl, Jemma Beggs reviews the centenary production of the classic musical, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang.

This piece is a part of Wales Arts Review’s collection, Roald Dahl | A Retrospective.

Claudia Lanza was born in Calabria, and first wrote about Roald Dahl in translation when researching “Language Sciences and Foreign Literatures” at Universita Cattolica del Sacro Cuore in Milan. She is currently researching for a masters thesis in “Terminology, Language sciences and Textual typologies”.