Robert Harris is the acclaimed author of eleven bestselling novels: the Cicero Trilogy – Imperium, Lustrum and Dictator – Fatherland, Enigma, Archangel, Pompeii, The Ghost, The Fear Index, An Officer and a Spy (which won four prizes including the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction) and Conclave.

Several of his works have been adapted for screen, including The Ghost, which was directed by Roman Polanski. His work has been translated into thirty-seven languages and he is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature.

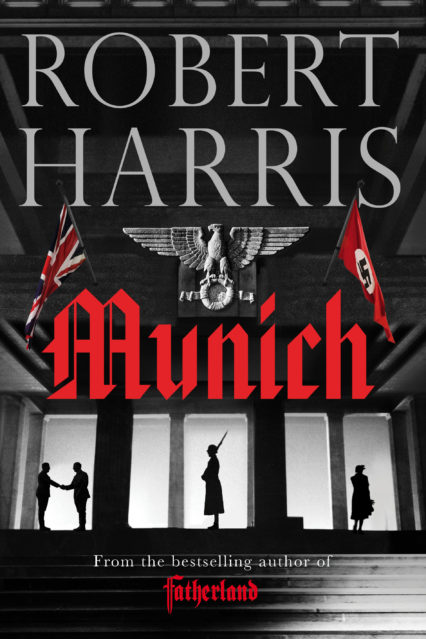

In the lead up to this year’s Cardiff Book Festival at which he is a headline speaker, the author spoke with Craig Austin about his highly anticipated novel Munich – a work that focuses on Hitler and Chamberlain’s historic 1938 summit – and his grave concerns about how stark warnings from history are being increasingly ignored.

It’s probably fair to say that when it comes to matters of historical record Britain is hardly renowned as a nation that deals well with either uncertainty or nuance. Our collective psyche is notorious for dealing almost solely in terms of heroes and villains, and a seemingly endless parade of received wisdom that comes neatly packaged in the union flag and liberally scattered with poppies.

It’s perhaps one of the reasons why Robert Harris has chosen the 1938 Munich summit as the focus of his much-anticipated new book, a work that will inevitably lead to a long overdue reappraisal of the role and motivations of Neville Chamberlain within one of the most infamous and misunderstood events in British history.

‘It’s one of those rare things that turns out to be almost the complete opposite of how it’s perceived’ the author tells me. ‘Which is just one of the reasons it seemed to be worthy of writing about. We have such a muddled view of that time that it was interesting to me to revisit something so famous yet at the same time hopefully have something new to say about it’.

‘I wouldn’t find it particularly interesting to write a book about the Summer of 1940 and how glorious it was,’ he continues. ‘Not because I don’t think it was glorious, but because everybody’s done it and everybody knows it. But to take something like Munich, which everyone thinks of as a disaster and as a victory for Hitler, and to suggest that it actually wasn’t a disaster and that Hitler felt strongly that he had actually come off worse; that seemed to me to be something worth doing simply because it would be more original. I’ve long had a fascination with the Munich agreement going back more than thirty years and for decades I’ve had half of the book in my mind; that is the character who’s one of Neville Chamberlain’s private secretaries, a man whose having troubles with his wife and how the problems that he’s having at home mirror the wider political problems. What I didn’t have was the German half, and it was when I thought of that last Summer that I could finally write the book’.

I put it to Harris that the manner in which history has sought to determine Chamberlain’s role in proceedings must have hung heavy upon not just the politician’s personal legacy but also the sensibilities of his descendants; ‘Yes, I think it has. His son died at a relatively young age in the 1960s and it must have been a burden. The problem was that Chamberlain was really caught in a pincer movement from both left and right. The Conservatives wanted to bury him for obvious reasons and actually so did Labour and the left; the Labour Party had opposed every measure of rearmament and indeed opposed conscription in 1939. So Chamberlain, dying when he did in 1940, he became a very convenient scapegoat, someone to blame. Whereas in fact, and I think it’s almost unarguable, that the time between 1938 and 1940 was very well spent in developing Spitfires and radar and perhaps above all it gave us a sense of national unity. A sense that no-one could say that we hadn’t done everything possible to try and avoid war and it was clear that there was no making peace with Hitler, that you could never trust him – and so the country did have a resolution to fight on that it might not necessarily have had otherwise’.

We live, unquestionably, in troubling times and it feels sadly timely that Munich arrives at a point when the world is in such a state of chaos and upheaval. A sobering reality that was evidently on the mind of the author at the time of writing: ‘It couldn’t really not be. I’d wanted to write this book for many, many years and books somehow select their own moment, when they’re ready to go, and suddenly this one seemed to be much more relevant. There is this sort of 1930s vibe around, a sense of great forces on the move and that individuals are slightly powerless in the grip of them. It’s an age of extremes, an age of nationalism. I find it absolutely staggering that you can turn on the TV and see Nazi flags being paraded through the streets of America and the American president is failing to condemn it.’

Yet it can be felt that the term ‘fascism’ is used all too frequently these days and I occasionally wonder if this regularity of usage almost diminishes the horrors of what’s gone before. ‘I think we are facing a form of fascism,’ Harris contends. ‘We’re facing a form of nationalism that’s strongly racist in its undertone; we’re facing a serious fracturing in Europe. The thing that’s most distressing to me about Brexit is that the positive case for Europe was never really put in the referendum. It was all stupid scare tactics, getting people like Obama to come over and lecture the British people about their pay packets. Where the real case to be made for Europe is that it grew out of the rubble of the second World War and the need for co-operation, that no-one should be able to opt out of it however difficult it might become.’

‘We have a completely different conception of Europe in this country,’ he continues, ‘because we regard the war as a glorious era in our history, whereas most of Europe views it as utterly wretched and shaming and appalling. It’s our myth. We happened to have a Prime Minister who was a brilliant orator and historian and he clamped a kind of legend onto 1940 so strongly, so powerfully, that it’s proved almost impossible to shift ever since. It’s partly because there is a strong element of truth to it. It was a glorious thing to have stood up to fascism, especially with so much of it resting upon a few hundred fighter pilots. It’s true. But there is another part to that truth, and that has to some degree been deliberately distorted ever since. To suggest that if it hadn’t been for Munich Hitler might have been deposed by the German army or that the Czechs might have held out for months, things which don’t seem to be true. Munich really saved our neck and yet all we get are endless films about Winston Churchill and “the finest hour”. Chamberlain has in many ways been written out of history and when you get these occasional appraisals of who was the worst British Prime Minister it’s often Chamberlain that is hovering around the bottom, just above Anthony Eden.’

‘We have a completely different conception of Europe in this country,’ he continues, ‘because we regard the war as a glorious era in our history, whereas most of Europe views it as utterly wretched and shaming and appalling. It’s our myth. We happened to have a Prime Minister who was a brilliant orator and historian and he clamped a kind of legend onto 1940 so strongly, so powerfully, that it’s proved almost impossible to shift ever since. It’s partly because there is a strong element of truth to it. It was a glorious thing to have stood up to fascism, especially with so much of it resting upon a few hundred fighter pilots. It’s true. But there is another part to that truth, and that has to some degree been deliberately distorted ever since. To suggest that if it hadn’t been for Munich Hitler might have been deposed by the German army or that the Czechs might have held out for months, things which don’t seem to be true. Munich really saved our neck and yet all we get are endless films about Winston Churchill and “the finest hour”. Chamberlain has in many ways been written out of history and when you get these occasional appraisals of who was the worst British Prime Minister it’s often Chamberlain that is hovering around the bottom, just above Anthony Eden.’

‘Yet now of course,’ Harris laughs. ‘We have two very contemporary candidates for that title. You wait for the worst Prime Minister in history to come along and then two come along at once!’

It is Brexit that has become something of a preoccupation for the author, as followers of his always entertaining Twitter account will attest. ‘I’m old enough to remember life outside of the European Union and what I really want to know from these Brexiteers is where we’re actually returning to. Is it the period just before we joined the European Union? Or the 60s? Or the 50s? Or the 30s? Or are we going back to Lord Salisbury or Disraeli. I mean, what is the perfect moment?’

“It’s no accident that Macmillan, Wilson and Heath all tried to join. They all felt that the British couldn’t go on either economically or politically outside of Europe. It wasn’t some sort of mad aberration, and that’s what we never heard about in the referendum; neither the emotional nor the historical case. Instead what we got was a really rather cheap Lynton Crosby scare campaign about emergency budgets, which quite rightly people resented. No-one likes to be treated like an idiot.’

The pressing issue of Brexit is already finding its way into great writing, not least within the pages of Le Carré’s A Legacy of Spies and a passage in which George Smiley pointedly declares: “I’m a European, Peter. If I had a mission—if I was ever aware of one beyond our business with the enemy, it was to Europe. If I was heartless, I was heartless for Europe”, and I am keen to understand whether this is a topic that Harris is likely to explore within the realms of fiction any time soon:

‘One thinks about how you could play your part, what bit you could do, and for me it’s story telling, the creation of characters and imagination. Yes, if I could find someway of doing it would be a good thing to do. It would be my contribution, if I could find the right means of doing it. Polemical fiction can be very boring and two-dimensional and shrill, whereas novels are about imaginative sympathy. But if one could find a way of writing it, I’d like to do it. It’s certainly something I’m giving some thought to’.

Where Harris is especially masterful is in his representation of contemporary concerns within a historical setting. ‘Historical fiction can also represent modern-day concerns,’ he explains. ‘The Cicero books are about what happens when a country surrenders to the mob, when the mob turns on the elite and the Republic collapses because of ambition and lying. All my books in a sense are political at heart and historical fiction is really contemporary fiction because what draws you to a subject is exactly the same as what draws you to a contemporary novel – what’s in the air, what’s bothering one, what concerns one. Pompeii is in a sense about the threat of climate change, the puniness of people and their ambition when compared to the power of nature. All of these things have a contemporary relevance but can at first glance seem purely historical.’

The author is understandably thrilled about the prospect of the RSC taking on his work in its upcoming production based on the Cicero trilogy. ‘It’s got a great writer, a great director, and a strong cast,’ he explains. ‘Not least Richard McCabe as Cicero. It’s got the most stunning set, which I’ve seen them rip out the heart of the Swan theatre to create. It will be a very dramatic and immersive experience. It’s been a completely new thing for me and just wholly enjoyable. Whatever happens, it has been a fascinating spectacle to witness.’

As far as spectacles go, we inevitably return to the issue of Trump, the rise of the American right, and the resultant interest in a number of books rooted in alternate history – the concept of bad life imitating great art. Philip Roth’s The Plot Against America has been a topic of much conversation and reappraisal but it would be amiss not to include Harris’s towering Fatherland within the same discussion:

‘Any way you can exercise your imagination on politics, any way you can try to create an imaginative alternate reality, anything that makes you think, that adds a few fresh ideas to the pot, is well worth doing’ the author argues. ‘These are troubling times and anything that one can contribute in terms of fiction is worth it. All of my books are about power, and to a degree are about ideas, and “what if” is a great way of deploying those ideas.’

For Robert Harris, now, as then, the future of Europe and the world hangs in the balance.

Robert Harris is in conversation with Marcel Theroux on 23rd September as part of the Cardiff Book Festival

Munich is published by Hutchinson on 21st September