In the second in a new series, Iwan Bala discusses the work that he identifies as the moment when he found his ‘voice’ as an artist.

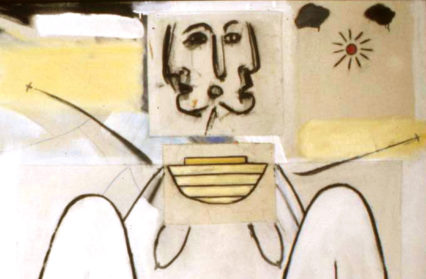

(Gwales/Ararat 1997 by Iwan Bala. Mixed media on canvas. 153x122cm)

Iwan Bala: I cannot be sure how many artists feel any sense of mission beyond making art and being successful at it. I imagine, that it is my upbringing and inherited assumptions that has given me an additional mission to try and engage in and with, my own culture.

I come from a generation raised within a Welsh-speaking tradition and alongside me are poets, musicians and writers who feel the same mission. With a few notable exceptions, not so many visual artists do. I wonder whether this is because the visual arts are not as embedded in the tradition of Wales in the same deep way as music and poetry. Equally, because of this, art has scope to examine and spread the message about this culture outwards into the world, and by doing so, become enriched. My visits to other cultures have been about people more than landscapes, and my art more about the ideas and the history that define these people, and not the scenery in which they live.

My aim in both my art and my writing has been, what I have termed, ‘Custodial Aesthetics’. In this I was encouraged by the role that the artist and writer David Jones ascribed to artists, their ability to act as ‘remembrancers’. People, who, in the present cast a gaze at the past as they simultaneously, move into the future. I compiled a book, ‘Certain Welsh Artists’ (Seren) 1999 as we were on the cusp of a new year, new century and new millennium. Several artists, those aforementioned ‘notable exceptions’ that I felt fulfilled the criteria of ‘custodial aestheticians’, feature in it. I am embarking on a three year PhD Fellowship at the University of South Wales to further this theme, and lectured on it in Wuhan and Hangzhou in April this year, also a Colloquium at the Research Centre Wales, University of Bangor called ‘WALES; in Search of Heritage’ in June.

The theme has been a constant for me since the 1990’s. I keep discovering, through travel, resonances in other cultures. It was an extended stay as Artist in Residence at the National Gallery of Zimbabwe in Harare in 1990 that gave birth to the idea. Later, Cuba’s domestic Santeria altars influenced my work for some time. My recent visit to China opened up for me, an ancient culture that has veered from adulation of the past, to a repudiation and destruction of its glories. The rush of modernisation, the literal bulldozing of ‘old’ China in the cities at the moment, is a concern to artists there.

I suppose, for me, the work that first encapsulated these concerns graphically, was ‘Gwales/Ararat’ of 1997. It was part of a group of paintings called ‘Haunted by Ancient Gods’ that won for me the Gold Medal for Fine Art at the National Eisteddfod of Wales in 1997, which by happy coincidence, was held in Bala, my hometown that year.

The painting depicts an island that is in the form of a woman giving birth (which incidentally and ludicrously was deemed ‘pornographic’ by some tabloid journalists, and elicited some controversy amongst the most staid of ‘Eisteddfodwyr’). The head is that of a Janus style figure, facing simultaneously the past and the future. Janus is a Romano Celtic deity, which gave us the name of the first month of the year, January. Ianws in Welsh, the month; Ionawr. A month in which traditionally, we look back at the past year, and forward to the next. In 1997, this was also more resonant as we were approaching the new millennium. Twin faced figures are seen in many cultures globally, I have in my possession an African carving that sports such a head, and I seem to find them everywhere, including China.

The title comes from an amalgam of the name of the mountain in Asia Minor (now Turkey) where Noah’s Ark is said to have landed as the Flood subsided, and an archaic name for Wales (Gwalia). But also more importantly, Gwales is the name of a mystical island off Pembrokeshire (possibly Grassholm) which The Mabinogi tells us gave sanctuary to seven survivors of war with Ireland, who are accompanied by the severed head of their Lord, Bendigeidfran, who nonetheless was able to recite stories to entertain them. This idyll lasted eighty years, in which time they aged not a day. Eventually and predictably, a forbidden door was opened, the head of Bran fell silent, and they were forced back to reality and to attend to the country of Wales (or Britain), which they had neglected. This island has also been a recurring image in my work.

There is much symbolism contained in the painting, and formally it also reflects my interest in the visual art of Latin America and Africa. It brings a lot of things together, and might be thought of as the first of what I call ‘visual essays’, which might be used as lecture ‘learning aides’. But I have also referred to these drawn essays as ‘Field-notes’, my reflections on experience, reading and engagement.

You might also like…

Described on more than occasion as the enfant terriblè of the Welsh arts scene, Neale Howells has exhibited all over the world to much acclaim. Although often seen as an outsider, Howells’ work is simultaneously welcoming and forbidding. Born in Neath and based in Port Talbot, his work remains that of a distinctive voice in Welsh culture, and one that will continue to be heard by a wider and hungrier audience as time goes by.

Iwan Bala is an artist and contributor to Wales Arts Review.