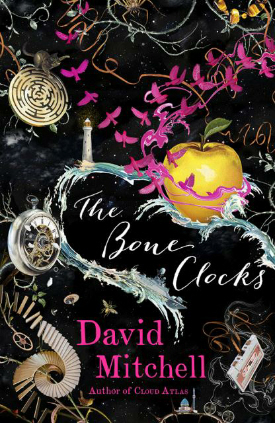

A lighthouse on a lone promontory above the waves; a smashed clock face, inner workings exposed; tape unspooling like ribbon from a cassette; steps spiralling off into oblivion; before you even open David Mitchell’s latest novel the dust-jacket reveals a little of the kaleidoscope of beautiful insanity you’ll find within its pages.

A lighthouse on a lone promontory above the waves; a smashed clock face, inner workings exposed; tape unspooling like ribbon from a cassette; steps spiralling off into oblivion; before you even open David Mitchell’s latest novel the dust-jacket reveals a little of the kaleidoscope of beautiful insanity you’ll find within its pages.

Moving on from the more straightforward, linear narratives of Black Swan Green and The Thousand Autumns of Jacob De Zoet, The Bone Clocks is a return to the multiple perspectives and genre-spanning narratives of earlier works Cloud Atlas and Ghostwritten. It is the tale of Holly Sykes, whom we first meet as a teenage runaway in nineteen-eighties Gravesend, and lastly, as an old woman living in a remote part of coastal Ireland. It is also the tale of a secret war, centuries old, between two factions of semi-immortals: one benevolent, the other decidedly more predatory. Holly begins as an unwitting pawn in the conflict; by the end, she will have become the key to its conclusion.

Once again, Mitchell has proven himself not only to be a versatile storyteller, but a master of both character and genre. Holly Sykes is a wonderful creation: vulnerable yet tough, with a big mouth and a heart of gold, who we see grow from a naïve and slightly self-absorbed teenager, into a woman who goes on to survive bereavement, illness and hardship, without completely losing her humour and spark.

The story is split into six different sections, each capable of standing on their own but still managing to form a cohesive whole, and whilst Holly only narrates the first and the last section, she is the sun around which the other characters, both malevolent and benign, revolve. This is not to say that other characters are shortchanged. From Hugo – Cambridge conman and lothario – to war reporter Ed – in denial about the fact that he may be addicted to the adrenaline rush of the warzone – to waspish author Crispin Hershey – fading ‘bad boy of English letters’ – Mitchell’s characters may sometimes be unlikeable, but they are always rounded and interesting, often to the point where you end up empathising with them anyway. The only characters are not as three-dimensional are the Anchorites – the group of immortals who serve as the story’s antagonists – however, there are reasons for this, which become clear as the story progresses.

Like Cloud Atlas before it, The Bone Clocks experiments with a different genre – and therefore a different style of writing – in each section, from the opening, which reads like a bildungsroman, to the ending – a coda, not only to the frenetic and ambiguous climax of the previous section, where good and evil meet for a final standoff, but to the entirety of what has come before – where Mitchell manages to conjure up a dystopian future of energy shortages and slow societal breakdown that is chillingly convincing; the real testament to technical craft and skill being that not one section feels written at the expense of another.

Like his earlier works, The Bone Clocks is sprinkled with references to previous novels – usually in the form of recurring characters – and is particularly resonant here with the novel’s theme of interconnectedness. The Bone Clocks can be read and understood in isolation without having read any of Mitchell’s previous novels, but provides some nice little Easter eggs for those who have.

Ultimately, The Bone Clocks is not only the story of the life of an exceptional individual, but a gripping tale of humanity’s rapaciousness and greed, not only our greed for resources but our greed for life. Admittedly, the science fiction elements could be seen by some as silly or pretentious, so if you are not able to suspend disbelief, or you have trouble with narratives that use multiple perspectives or straddle more than one genre, then this will be a book that might give you trouble. But look past all that, invest yourself in the novel’s world, absurdities and all, and you are in for a wonderfully immersive treat.