What goes into the making of a great album? From the creative throes of songwriting to the sometimes-spontaneous, sometimes-arduous process of recording a full album, Wales Arts Review dives into the making of some of some iconic albums from Welsh music artists in our new series ‘The Making Of… ‘. This week, we take a look at The Big 3 by 60 Ft Dolls.

The Big 3 came in at number 12 in our 100 Greatest Welsh Albums of all Time and was thusly highly praised, with Wales Arts Review writing: “The influences on the song writing of the 60 Ft Dolls is writ large on this album – from The Jam to Thin Lizzy – that it’s almost like a testament to what Britpop might have been had it not been so smug. […] The record also makes a strong case for Carl Bevan as the finest rock drummer of that era, and tracks like “No1 Pure Alcohol” and “Pig Valentine” bely an energetic craftsman amidst all that balls out rock n roll. The Big 3 is an album of high energy, high intensity, and it’s laden with great rock songs. A taster of their fearsome reputation as a live outfit, it’s one of the greatest guitar albums ever recorded.”

So, what was the experience like in the studio? We hear from 60 Ft Dolls on the making of The Big 3.

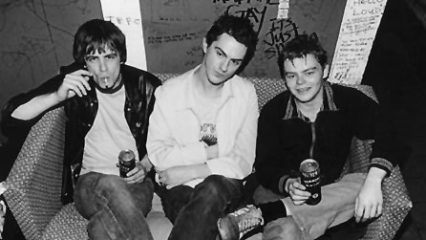

We demoed the songs in a small studio in Newport called LeMons and then recorded most of the album in twelve days at Rockfield Studios in the autumn of 1995. Rockfield being just up the road from Newport but remote enough so that we could concentrate on the recording without being too distracted by what was happening back in town. Al Clay produced the record, and as Carl remembers, injected some much needed discipline into the process.

‘Al Clay was like a drill sergeant and made me [Carl] clean and polish my drums and cymbals and then stand to attention by the side of kit. This made absolutely no difference to the sound but it was a statement of intent.’ In those days just about everything was analogue [tape], which meant a lot of pre production, as you couldn’t really afford to go back and fix things as studio costs were substantial, so rough demos were a cost effective way of drafting songs toward the final recording session. Geffen wanted a fresh pair of ears to mix so we sent the tapes to the USA where the album was remixed by Lou Giordano [who’d recently produced Copper Blue by Sugar].

We released our early singles on independent labels which allowed us to negotiate separate deals in the USA and UK, however, while there were no real industry hurdles, RCA and Geffen occasionally locked horns, which meant we might find ourselves doing two separate videos for the same song. Sometimes a band will procrastinate and tie themselves up in knots trying to get the right producer, but the wrong’ producer can actually ruin a record. This usually happens when the producer tries to hitch his own creative ambitions to the bandwagon rather than help the group realise the possibilities that exist.

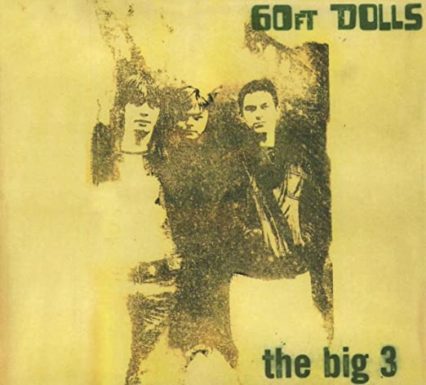

Al Clay had catholic tastes and we’d start the day by listening to a lot of different types of music while discussing ways in which classic records had used arrangements and then maybe try some variations. The biggest headache was choosing the album art work. RCA kept sending us these Britpop ideas, and we also had a few designs drawn up by Jamie Hewlett of Tank Girl fame. In the end Pennie Smith came down to Newport and took some black and white photos of us messing around the Crindau Industrial Estate and we used one from that session. Geffen Records then sent a photographer over from America and that’s why there’s a different sleeve for the USA release, although my preference is for the UK Pennie Smith sleeve. The title ‘The Big 3’ was borrowed from one of John Lennon’s favourite groups ‘The Big Three [Liverpudlian band from the early 60s]’. The literal association with the word ‘Big’ and the fact that there were three of us seemed like a gift.

The songs had been road tested and demoed so the album is basically a document of our live performance. For the guitar nerds I used my Gibson 335 on just about every track and also a Les Paul Standard and Telecaster for the overdubs. I’m not a fan of effect pedals and kept those to a minimum. If you want to get a good distorted sound you just have to crank up the amp until it starts to break (obviously, you can’t do this in the house). There are no digital processers or plugins involved, just hot valves, drums and wires.

Sometimes I would write something at home or maybe just bring in an idea and have the band work it up in the rehearsal room. There’s a track on the album called ‘The One’ which Mike wrote. I remember going to the shops to buy some cigarettes and by the time I got back he had written the song. He looked puzzled, like he didn’t know where it had come from. That’s the mystery of the creative process. You can sit there all day and nothing happens and then the idea just reveals itself. You don’t really need anything to write a song except an idea. I wrote ‘Stay’ when I was driving back from London. Just kept singing the idea over until I had the first verse and chorus then worked it out on guitar when I got home. Those were the days before convenient recording devices and the rationale was, if you couldn’t remember how the tune went it probably wasn’t worth remembering. ‘Hair’ was a love song Mike wrote about his romance with Donna Mathews. It’s my favourite lyric on the album:

Love your hair, and everything below it

I don’t care if you cut it or you grow it.

Love your hair, it’s yellow and it’s brown.

And everywhere, it follows you around

Carl remembers that breaks in the schedule would often come in the form of Kingsley Ward who would shamble in reeking of cow shit to borrow a screwdriver and spin a yarn or two: “There was me, Robert Plant and Freddie Mercury in Freddies Rolls Royce driving around Monmouth …”’ Implausible as it may seem, we were quite professional in the studio, however, we did have to rush Mike to hospital after he broke out with a bad case of The Singing Detective, or psoriasis, the condition where your skin gets covered with silvery scales. The doctor put it down to stress and sure enough he was okay a few days later. Bands can often go native in residential studios, but Rockfield does have a mystical ambience about it that keeps you in check.

Two of the songs were recorded separately form the Rockfield sessions. The penultimate track: ‘Terminal Crash Fear’ recorded in LeMons and produced by Richard Jackson of Novocaine, and ‘Pig Valentine’, produced by Jon Langford who showed up at the studio with a crate of wine and a Vox amp. That was the most alcohol fuelled session I can ever remember. In fact, I can’t even remember recording it, but I must have been there I suppose.

Occasionally, I’ll hear a track on the radio and think it still sounds exciting and like we recorded it yesterday. The danger of recording is in the opportunity to make something perfect, there’s no surer way of killing an idea than working it to death. I recently read an article by the crime writer James Lee Burke who quoted Jack Kerouac as saying, ‘Your art is the Holy Ghost blowing through your soul.’ I like that quote because I think it highlights the difference between the revelation and the realisation – or the art and the craft.

Ideas don’t come easy, but you always have the craft [realisation] which you can apply to the art [revelation]. In other words, recognise the gift when it’s offered to you but also understand that your part of the bargain is putting the graft in. Making music can be scary but you have to trust your intuition. You don’t need to stare at the visual representation of pro tools on a computer screen to tell if something’s out of time or out of tune, you just need to listen and respond. The Big 3 was originally released in January 1996 and then rereleased in 2015 with a John Peel session and some B sides. We’re forever grateful to everyone and anyone who still listens to the record after all these years. Thank you.