Emma Schofield looks at the increasing trends of literary tourism, and the dangers of reducing our literary heritage to isolated reference points on a map.

Fancy spending your holiday pulling on your walking boots and trekking through countryside in search of scenes from a favourite novel? Or reaching for a guidebook and spending an afternoon following a heritage tour for an author you have a particular interest in? If you answered yes to the above then you certainly wouldn’t be alone. Research carried out as part of this year’s World Book Day celebrations indicated that more than half of British holidaymakers would visit a literary attraction while on holiday in England. In a competitive marketplace companies and agencies are increasingly drawing on fresh ways to attract tourists, with the rise in literary tourism a clear example of how areas are attempting to pull in new visitors. With organisations keen to offer interactive literary maps which aim to guide interested tourists to so-called literary hotspots, literary tourism can be a way of encouraging potential visitors to consider points of cultural interest on their holiday.

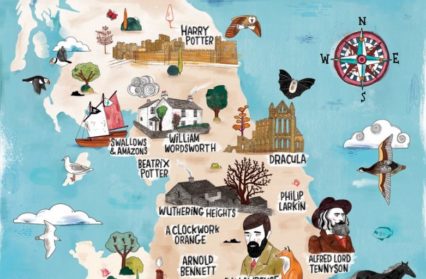

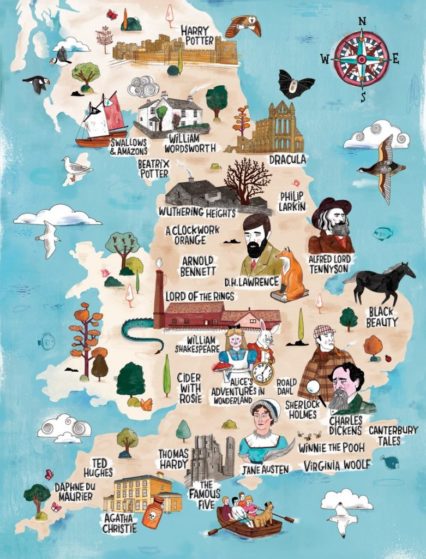

But there is a downside to these increasingly popular mapping exercises. Following on from the furore surrounding BBC Newsnight’s debate over the Welsh language earlier this month, another Twitter storm broke out last week when a literary map produced by Visit England was retweeted by the BBC Britain and Love Great Britain accounts, both of whom incorrectly labelled the map as a literary map of Britain. This labelling was in spite of the fact that the map had clearly left Wales and Scotland blank and had cut Ireland out of the picture entirely. Worryingly, it appeared to take a substantial number of comments and complaints from other users to bring this to the attention of BBC Britain and Love Great Britain, before both posts were eventually deleted. While it is undoubtedly alarming that accounts such as BBC Britain apparently managed to interpret an English map as a British one, the literary mapping process used to attract tourists is in itself often a confused and limited exercise.

But there is a downside to these increasingly popular mapping exercises. Following on from the furore surrounding BBC Newsnight’s debate over the Welsh language earlier this month, another Twitter storm broke out last week when a literary map produced by Visit England was retweeted by the BBC Britain and Love Great Britain accounts, both of whom incorrectly labelled the map as a literary map of Britain. This labelling was in spite of the fact that the map had clearly left Wales and Scotland blank and had cut Ireland out of the picture entirely. Worryingly, it appeared to take a substantial number of comments and complaints from other users to bring this to the attention of BBC Britain and Love Great Britain, before both posts were eventually deleted. While it is undoubtedly alarming that accounts such as BBC Britain apparently managed to interpret an English map as a British one, the literary mapping process used to attract tourists is in itself often a confused and limited exercise.

So just what is the problem with literary maps as a tourist mechanism? After all, it could be argued that the trend for literary tourism is just an extension of the spatial turn which came to the fore of literary studies in the early twenty first century. Yet where literary topography endeavours to explore the connections between places and texts, literary tourism seems increasingly to focus on pinning a text or author to one single place. Not only is that unrealistic, but it is also at odds with how we frequently explain our own sense of identity. Most of us would agree that our identity is made up of a range of places, people and influences; very few of us would likely argue that our identity is solely tied to a single place of significance.

As a result of this attempt to tie authors and texts to specific places, the premise of these literary tourism maps is often confused. Visit England’s map encourages users to ‘explore England’s literary hotspots’, before presenting an interactive map which jumbles authors, book settings and film locations together without any real distinction. Of course, not all references on the Visit England map are confusing; The Canterbury Tales are used to pinpoint Canterbury and Cornish author Daphne Du Maurier quite rightly represents the area in which she lived and wrote. Unfortunately, not all of the map is this clear. Northumberland, for example, is labelled with the words ‘Harry Potter’ on the basis that Alnwick Castle was used as Hogwarts in the accompanying film franchise.

The second problem with this kind of approach is that such mapping exercises isolate authors and works of literature by attempting to tie them to a single place, often making no mention of any other relevant locations. For example, Visit England situates Roald Dahl in Buckinghamshire, an area in which Dahl did spend his later life and which houses the Roald Dahl Museum. The problem is that the map, and its accompanying webpage, make no mention of anywhere else of relevance to Dahl, entirely ignoring the Welsh, Norwegian and American connections which make up a significant part of Dahl’s identity. In contrast, Visit Wales lays claim to Dahl as a writer with strong Welsh connections and encourages tourists interested in the author to visit Cardiff Bay. Some joined up thinking between Visit Wales and Visit England might have encouraged tourists interested in Dahl to consider both places of relevance to the author and would have more accurately reflected the multiplicity of Dahl’s identity.

Similarly, the Visit England map claims Birmingham as an important site for J. R. R. Tolkien fans to visit, assuring potential visitors that ‘Sarehole Mill was once a favourite playground for Tolkien and his brothers, the Mill and surrounding areas are believed to be the inspiration behind Hobbiton and the Shire’. Meanwhile, the Visit Wales and Literature Wales Land of Legends interactive map argues that Buckland Hall in Mid Wales may have been the inspiration behind these fictional depictions. Such claims and counter-claims are not a new feature of literary analysis, but it seems disappointing that potential opportunities to share literary sites and encourage wider tourism across Britain as a whole are being ignored. It is natural that England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales will all want to promote their own literary hotspots, but when contradictions arise or obvious connections are ignored, the whole exercise meanders into the absurd.

There is a very real danger that by continuing with such tourist-focused mapping exercises we encourage users to see authors and texts in a very singular and isolated way. Not only is this standpoint frequently incorrect, but it also has alarming implications for how we view identity and cultural heritage more widely. Attempting to isolate authors and texts from complex backgrounds and pin them to one specific location on a map is, at best, hugely reductive. From the perspective of literary tourism we should be encouraging visitors to see the bigger picture, to make connections between different places of significance to authors or texts. Those interested in Harry Potter might be encouraged to visit Northumberland and see the castle used as Hogwarts in the films, but why can’t they also be encouraged to visit Edinburgh and see the city where J. K. Rowling lived while writing the Potter series?

In a turbulent Brexit era where the nation seems evermore divided against itself, alarm bells should be ringing at any exercise which promotes viewing literary connections in isolation. Geographically, Britain and Ireland occupy relatively little space on the world atlas, but boast an impressive literary heritage in which English, Irish, Scottish and Welsh literary heritage often interconnects. As promoters of literature in Britain we should be celebrating these connections, not working against each other in a competition to encourage visitors to see authors or texts in isolation. Pride in an area’s connection to a literary work or figure is natural and positive, but our literary culture is founded on imagination and diversity. Attempting to pin works of literature to a single specific place only serves to undermine the richness of our complex identity and shared literary heritage.