Co-curators Dr Natasha Mayo and Zoe Preece gather together student thoughts on their exhibition ‘The Sensorial Object’ held at Craft in the Bay in January 2015. The contributions from students include: Charles Conreur, Chloe Monks, Anne Frost, Ellie Cooper and Tsz Ying Fung from the ceramics department at the Cardiff School of Art and Design and reflect the experiences of all students involved in the project.

The craft object inhabits a unique vantage point in art education, one that firmly retains connection to the home and the domestic whilst at the same time encouraging discussion of the diversity of fields that surround it, from aesthetics, philosophy to social science to name a few.

For students, this unique positioning of aesthetic understanding can enable deep appreciation of the capacity of art to speak beyond the exhibition space, allowing them to evolve concepts, test out possibilities and push the boundaries of the discipline, all the while understanding how new territories can arise from a familiar standpoint.

This article focuses on student experiences of the ‘The Sensorial Object’ exhibition. It demonstrates how a range of learning and teaching opportunities not only used the exhibition as a site of debate but in turn, contributed to a rich and cross disciplinary body of research exploring the relationship between craft and sensory perception.

The following text interweaves some of the discussions that took place in response to the exhibition. Each student review is prefaced by the physical sense with which it most closely aligns and is accompanied by brief explanation of the relevant learning and teaching opportunity and its wider context, offered by artist’s statements or theoretical exerts taken from the catalogue.

Taste: the sensory impression of food or other substances on the tongue.

Gareth Dobbs (Head Chef at Duck Egg Bleu) exert from the Sensorial Object catalogue:

It begins with changing the menu I suppose, well maybe not, it’s a process . . . I’ve got a little black book where I write all my ideas down and that idea might not take shape straight away. There are dishes that I’ve come up with five years ago that I still haven’t made . . . they’re ideas.

I like taking dishes that are classics and making them a little bit quirky like the ham, eggs, chips and peas. So when you order it you’re not going to know what you’re getting. It’s about doing something that surprises people a little bit.

Charles Conreur:

Gareth Dobbs is the head chef at Duck Egg Bleu a local restaurant in the Canton area of Cardiff. Now a chef may not be your first thought when thinking about an art exhibition but many consider cooking an art form. Dobbs was invited to take part in the opening of the ‘Sensorial Object’ exhibition and devise a series of culinary exhibits based on familiar everyday dishes but subject them to his ingenious twist in textures and presentation. Along with other students I helped with the preparation of the canapés, in the smooth running of the makeshift gallery kitchen but most importantly, in convincing visitors on the evening of the private view to taste them!

People were invited to taste an unusual and surprising mix of flavours, colours and presentation. They were asked to re-discover familiar well known dishes in unfamiliar ways. One that stood out as a favorite seemed to be the crème brûlée presented like a soft boiled egg in a real egg shell yet as you delved into the crème a mango heart was revealed. What a way to finish a meal and start an exhibition!

The experience acted as an aperitif preparing your senses to better receive the other artworks on display.

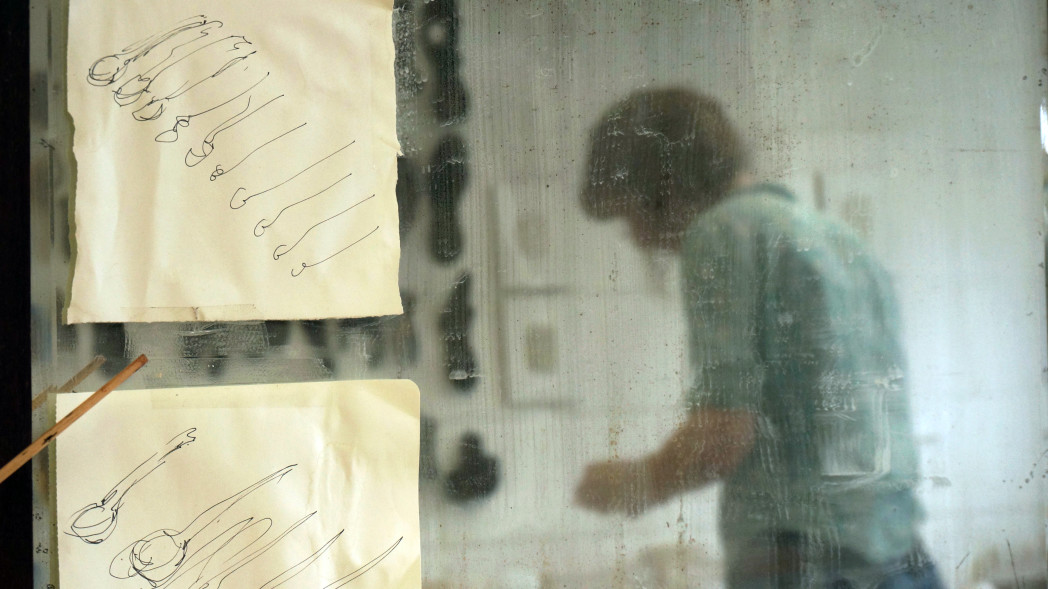

An exhibit most affected by a heightened sense of taste was perhaps ‘No Tangible Object’ by Zoe Preece. The work comprises multiple spoons carefully balanced next to one another, each delicately spilling thick syrup like substance, drawing your gaze into the familiar setting of a domestic still life but at the same time evoking a sense of unease.

The work instills certain nervousness in a viewer, as the dripping substance prompts you to grab the spoon in an attempt to stop the spill. You become involved, imagining how it might feel to hold the syrup, feel it escaping through your fingers, and how in might taste. For me, the work summoned sweet nectar, a taste of honey leading to a sensation of comfort. The piece prickled your imagination making memories of previous experiences come to life.

Teaching and Learning Opportunity

The ‘culinary experience’ at the private view was filmed and subsequently played as part of the exhibition itself. Perhaps due to the novelty of the experience, visitors were surprisingly willing to give a far more holistic account of their encounter with taste than they would ever likely give of their visual response to an artwork. They walked us through, from expectation to sequential stages of their taste experience.

Based on this observation, students were asked to recognize the speed with which they ordinarily read art objects, that in many ways it is as though the body arrives at and responds to stimulus before we are even aware of its activity. They were then asked to find ways to slow this activity down by speaking, writing and drawing the successive stages of their visual encounter, in order to better understand their activity of perception.

SOUND: or audition is the ability to perceive sound by detecting vibrations, changes in the pressure of the surrounding medium through time.

Dot Young (Dot Young, Theatre Practice: Prop Making, Royal Central School of Speech and Drama) exert from the Sensorial Object catalogue:

Our encounter with an object is a multi-sensory experience. We draw on the resonances that the object’s aesthetics, form, texture, colour and scale have in relation to our personal and cultural reference points. We consider the context that the object sits within, and its physicality in relation to our own physicality. We develop personal narratives for objects and social relationships with objects. We are able to feel an affinity with form, we can become unnerved, reassured, moved and stimulated by them. We consciously and unconsciously ‘read’ objects and strive to develop an individual understanding of what they are and what they mean to us, in order to make sense of our world and ourselves.

‘Aurality of Objects’ considers what our sensitivity to, and understanding of, an object could be, if we were to develop the ability to sense and hear the ‘aural fabrication history’ of an object when we encounter it.

Chloe Monks:

It was not until the Violinist Bethan Frieze responded to Rawson’s work through music, that I had a connection – where the whole world shrinks and a huge sense of peace resides. The music drew out a narrative, unraveled stories crystallized within the object’s form, and memories, experiences and life emanated from this quiet, silent material of glass. We had access to its internal realm.

The condensed layers of fabric printed onto glass were played like mental memories contained within our home. The violin gave the work a sense of closure; it completed our understanding of it.

Rawson’s work silently explores remembered sensations of time, and music; its sequences, layers and narrative, gave it voice.

In contrast, Anne Gibb’s work judders, swells and spikes. Her use of material heightens the sensorial landscape of objects. She works in an intuitive way and a sensitivity of touch is conveyed through each piece as if a single line of playful notation. Each object is cast from the delicacy of slip cast bone china, conveying a rhythm of sensation from sharp edges, empty spaces to smooth pools, igniting our need to reach out and touch.

Her work composes a tacit journey of variable clusters of action akin to a musical score, engaging with our senses of sight, sound, taste, smell and touch.

Teaching and Learning Opportunity

Bethan Frieze is an exceptional musician. She is one of the acoustic group ‘The Amigos’ and teaches in a multidisciplinary team with children from challenging backgrounds. She intuitively responded artwork in the Sensorial Object exhibition with her violin, taking each exhibit in turn and exploring its materiality, function and perceived sounds of production, as well as forging connections to memories of her encounters with similar values.

Of particular sensitivity was her response to Emma Rawson’s work, in which she used the expressive association between the sound of a suspended seventh and a sense of tension or human angst. A succession of seemingly incomplete progressions prickled the air with lingering expectation and when she eventually answered their call it was with a thin, delicate tone creating a poetic and tender solemnity. The significance of this approach was rendered poignant when reading Rawson’s statement which describes the piece as a response to the experience of sitting with a terminally ill loved one and considering the ever diminishing scale of their surrounding world.

The ‘sounding of objects’ introduced students to Synaesthesia and encouraged them to appreciate the richness and transferability of creative languages from music, word, drawing to ceramic/glass/wood and how one can inform another in finding ever deeper understanding of the potential meaning of an object.

Vestibular: a sense of spatial orientation, providing the leading contribution to sense of movement and balance.

Ainsley Hillard (Artist) excerpt from the Sensorial Object catalogue

I am drawn to specific spaces and want to question how do we grasp space and place? I strive to evoke the sensual, material, aesthetic and emotional dimensions of place.

I am interested in materializing the immaterial. I want the viewer to be drawn in to the structure of the fabric, and embrace an embodied and haptic means of looking, mapping the surfaces of objects, giving close attention to materiality and what David Michael Levin terms as an ‘alethic gaze’ a bodily felt visual encounter with what is being seen.

Anne Frost

Ainsley Hillard’s ‘A Sun-beam in a Winter’s Day’ is the first piece any visitor to The Sensorial Object exhibition encounters – it welcomes them into space.

It is a triptych. The carefully woven panels have an ethereal sense – they waft gently where they hang; responding gently to your movement behaving like curtains at an open window. As you stop to contemplate you find yourself oscillating between mere observer and being pulled into a space beyond their surface. You find yourself reminiscing how it felt to enter into similar spaces, transported by a physical tug against your frame into another place and time.

Whilst the piece is monochrome the illusion of light is striking; it evokes the feel of the sun’s heat against your skin through the window. The experience is familiar, speaking strongly of human contact and of the sounds, sights, smells and touch of home.

Teaching and Learning Opportunity

Artist and Co-curator of the Sensorial Object exhibition Zoe Preece introduced students to the proposition that, our ability to experience our surroundings is constrained by the very nature of our perception.

Firstly, there are aspects to any experience of which we remain unaware; they may reveal themselves at moments when one is more receptive but stay hidden until the most conducive conditions arise. Secondly, there are constraints that we need to impose on our own activities in order to give focus and aid concentration on certain experiences over others.

To enable sensory understanding to thrive given the limits of our faculties often demands a shift in priority from the dominance of vision toward other modes of interaction with the world.

The ‘materiality of drawing’ workshops explored the Angela Eames quote: ‘it is touch which informs the artist of the nature of the material and sight which completes the understanding’. Students’ first met in pairs to draw objects from a verbal description of its appearance and then from a description based solely on touch. The outcomes revealed the potential of tacit understanding; how the body itself contains knowledge of prior sensory encounters.

To keep sense of touch prominent in subsequent drawings, Preece asked students to create their own tools from found materials and source potential medium. Whilst remaining mindful of the function, gesture and impression of tools already in use in their artistic practice, the students drew the objects again. The unpredictability of materials and medium usurped their control and posed unusual textures and actions in relation to the objects. The emphasis on tacit exploration enabled the students to uncover and explore facets of the object otherwise hidden by direct observation.

Proprioceptive: the ability to sense the position, location, orientation and movement of the body and its parts

Bonnie Kemske: exert from the Sensorial Object catalogue

Touch is the first sense to appear in the developing foetus and the last sense to leave us as we near death. We touch and are touched, and we are not separate from the object we hold in our hands or against our bodies – to experience the object is for it to become part of us. Maurice Merleau-Ponty said: ‘…there is overlapping or encroachment, so that we must say that the things pass into us as well as we into the things.’ In this way, there is a blurring of subject and object.

Elloise Cooper

Within Pigott and Murphy’s work there is a confusion of the senses, where the simplicity of touching a small teacup causes a barrage of vibrations, setting in motion a series of well tuned ceramic gramophones creating an intriguing amplification.

For a moment confusion arouses curiosity and there is a real sense of finding new connections with such a commonplace item. Touching and then hearing the effect elsewhere, draws you deeper into the material, into the sound of the clay, the glaze and their form. The use of Lustre on the gramophones intensifies the sonic produced by the intricately designed systems. It resonates a tone that compliments the delicacy of the teacup and the exquisite nature of gold.

The often tenuous connection between object and material are quite literally made to sing, creating a tiny symphony through the simplicity of the everyday.

Teaching and Learning Opportunity

The Sensory Story workshops explored how stories can be created through direct sensorial

stimulation as well as word, to the benefit of individuals with Profound and Multiple Learning Disabilities (PMLD). They are devised to provide a dynamic way to encounter stimulation, boost learning and communication skills by offering enriched experiences and knowledge built from repeating sequential narratives with associated smell, feel, touch and taste. A similar approach can be used for individuals with autism and dementia in order to build or re-build their system of sensory reference previously too concentrated, dislocated or in some cases forgotten all together.

Students were asked to construct their own sensory story from the Sensorial Object exhibition prompting them to narrate their experience and uncover the capacity of an artwork to contain small worlds of experience.

Vision: The ability to perceive through the organ of the eye

Jo Grace (Founder of Sensory Story) exert from the Sensorial Object catalogue

When we live without paying attention to our senses we experience a dulled version of life. Have you ever listened to a seagull’s cry and realised that it sounds like a cat’s meow or felt the texture of a feather and been reminded of a gentle breeze. Our senses can surprise us; can contradict what we thought we knew. The Sensorial Objects in this exhibition ask us to pay attention to our senses so we might find surprises within our daily life.

Fung, Tsz Ying

Most of the time our senses and reaction towards things around us are informed by past experience. For instance, when we see a red-traffic-light we stop; ice makes us think of cold; cotton we associate with softness. Our brain analyses information and gives us a logical response to objects or situations we come across. We gradually build a system of reference.

If I attempt to focus on Elaine Sheldon’s Atelier from the perspective of each of my senses, through sight I see a bubble, a giant egg, I think of bubble gum; from sound I hear a popping, bursting sound from the friction of the lamp against the table; from touch I feel elastic, plastic and warmth and the smell of rubber. I find that I easily and fluidly overlap my senses to gain experience of what is in front of me.

It is very difficult to imagine what experience of the world is like if you are not able to do this. To have difficulty in sensorial, emotional or social reciprocity is to encounter the world and your place within it in a very different way.

Teaching and Learning Opportunity

The final teaching opportunity we staged as part of the exhibition was in fact to install another exhibition that ran at the same time.

The artist Becky Lyddon’s exhibition Sensory Spectacle travels internationally to bring awareness to the public of sensory processing difficulties encountered in the Autistic spectrum. Becky’s interactive and installation based work is created in response to case studies of individuals on the spectrum. The exhibition was staged at Cardiff School of Art and Design.

It included ‘Being Ben’, a series of clear plastic boxes into which you enter your head to encounter a wall of sound recorded from noise taken from the immediate environment. The sounds of doors opening, footsteps, talking and machinery are subtly over-laid and played at different volumes. The effect, is disorientation and inability to detect one sound or its orientation over another. In ‘Lola’s World’ a fragmented and over-laid mirror created a similar experience through vision. These exhibits and others, together with a range of experiential workshops encouraged students to question patterns and tendencies in their own ability to process sensation and to better understand what was actually taking place for them when they returned to experience artwork in the’ Sensorial Object’ exhibition.

The learning opportunities devised alongside the exhibition are part of ongoing research exploring ‘The Exhibition as a Site of Debate’. It is a fascinating aim, to find new ways to explore artwork. In devising these interventions, we looked for dynamic vantage points that could enable an audience, students or public, to engage with new ways of looking at the work and learn about different modes of interpretation.

When the students returned to their studio, they did so with a heightened appreciation of the capacity of art to speak beyond the exhibition space to science, health care, music, cuisine to name a few. With each collaboration or crossover of spheres of knowledge underpinned by a growing understanding of the relationship between craft and the nature of sensory perception.

What had begun as a straightforward curatorial proposition with the humble aim of exploring the sensory capacity of the domestic object had evolved into such a rich, diverse, multi layered and cross disciplinary body of research that we have now come to appreciate the particular formation of exceptional artists and thinkers that culminated at Craft in the Bay during January and February 2015, as a platform from which the project will continue to grow.