translated by Howard Goldblatt and Sylvia Lin.

436 pp., Edinburgh: Canongate, 2013.

What’s in your heart? Is it a demon? Or a treasure? Or perhaps a bit of both?

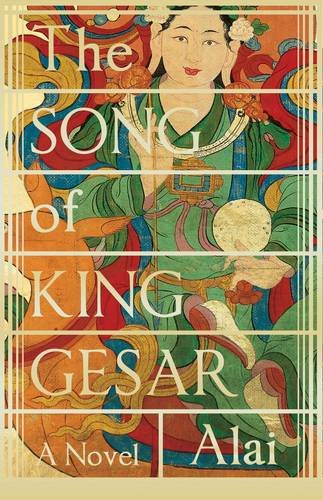

Tibetan writer Alai’s novel The Song of Gesar, translated from Chinese by Howard Goldblatt and Sylvia Lin, explores what’s in the hearts of both humans and deities. It’s an epic story from Tibet, told by generations of bards, and now in a written format by Alai; the author of a number of novels and collections of poetry and short stories (besides Gesar, only his novel Red Poppies seems available in English).

The novel starts off quite gently, lulling the reader into believing this might be an easy read about the far-off land of Tibet. But soon the reader is hit with paragraphs such as this:

Meanwhile, the demons howled with laughter as they feasted at a banquet of human flesh. First to be eaten were those who had spread rumours. Their tongues were cut out, then their blood was poured into jars and placed on the altar as an offering to evil deities. The demons consumed some of these poor souls, but there were more than they could eat, so the rest were left without their tongues, weeping in remorse and pain. Their wailing streamed past people’s hearts, like a dark river of grief.

Such passages make the reader (and the characters) wonder whether the gods actually care about humans. Will they help humans or do they expect humans to sort things out on their own? What actually would be best for people? And what are the deities up to anyway? As this might show, The Song of Gesar is part of Canongate’s brilliant Myths series (which also includes work by Ali Smith, Klas Östergren, and Margaret Atwood, among many other important writers), and it’s a vital addition, as this is the first time the Tibetan story has appeared in English.

Alai considers these questions of gods and humans, good and evil, in beautifully written (and beautifully translated) turns of phrases:

The next day the sky shone bright and clear, when the old steward stood on a dais in front of the fortress. The snowdrifts were silently collapsing under the heat of the sun, with water gurgling beneath the white blanket. It was nearly noon, but not a single person could be seen on the roads that led to the tribal lands. The old steward sent soldiers to find them, while he sat on the top tier of the fortress, neither drinking tea nor touching the cheese that was brought to him. Eyes closed, he could hear the snow melting, and when he opened his eyes, he saw steam rising in the sun’s rays. Still no one came. The heat from the sun weakened and, battered by an icy western wind, the steamy vapours turned to grey mist and fog. He sank into gloom. Perhaps he had outlived his usefulness; perhaps he deserved to be abandoned by the people.

Gesar, the cultural hero of Tibet, the lord of Gling, has fascinating experiences, and at last anglophone readers have access to his story.