Nathan Munday reviews The Tomb Guardians by Paul Griffiths a metafictional journey exploring the artistic and political significance of four portraits.

Paul Griffiths’ latest novel is both a ludic tapestry and a masterclass in ekphrasis (a textual response to a work of art). Following on from the highly praised Mr Beethoven (2020) and his counterfactual presence in the United States, we’re taken on a metafictional journey to Judaea and Germany. Most readers will be familiar with the Biblical account of the Resurrection and how the young Apostle John sprinted to the sepulchre ahead of Peter. What did he see? Linen, yes, but what else?

An absence.

We’re told that he gazed into that void, ‘and believed’. The Tomb Guardians is a creative pause on that sacred threshold, and it’s from that liminal space that this tapestry is expertly weaved.

The Subject

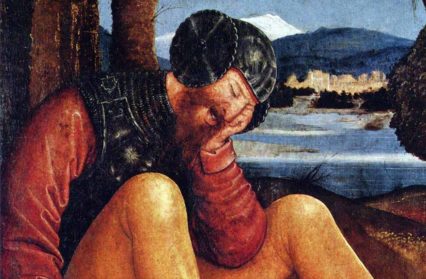

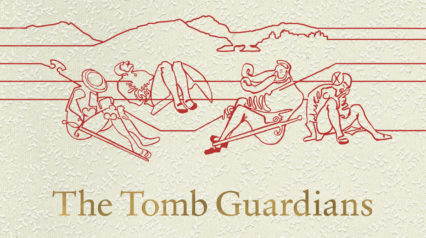

The front cover presents an artistic interruption in the musical staves. The subject of the novel is introduced, namely, the curious paintings of German Renaissance Master, Bernhard Strigel (c.1461-1528). This visual caesura is vaguely familiar to us. Those of us who’ve read Mr Beethoven appreciate the continuation in cover design which is thematically mirrored within. Notes of interpretation, the power of imagination, silence, noise, fact, and fiction sound out from both novels.

We also recognise the quartet who squat in the subliminal corners of our Sunday-school-minds. Yes, those tomb guardians that ‘became as dead men’ when the momentous event occurred (Matthew 28:4).

However, when we open the book, we find these nameless guardians wide awake. Confusion erupts because the well-sealed tomb is empty and one of their number has gone AWOL. Two conversations take place: the first involving an anguished lecturer and a friend exploring the works; the second is an act of trespass on the reader’s part as we enter the artwork and listen to what the guardians have to say for themselves.

I must confess that, at this point, I was tempted to peek at the end of the novel, but I resisted and read on.

The Hidden Warp Threads

Pause a moment and walk towards the back of the tapestry. There are many hidden warp threads, dangling colours, and cryptic silhouettes hidden by the haze of workmanship. Reformation looms in the background as does the hushed whispers of Passion Play and Apocrypha. These paintings appeared in the 1520s, that rupturing post tenebras lux period when Europe was dragged ad fontes (back to the sources) by the combined power of spirit and printing press. Keith Miller is right when he says that this is a novel ‘that occupies itself entirely with voices’, and voices were certainly re-emerging in this noisy period thanks to Gutenberg’s invention.

The presence of these warriors seems radical. No ultramarine lady here, or Norman Messiah there. Just German soldiers. The juxtaposition between ‘high’ and ‘low’ can be heard throughout, but so is the absence of the voice we’re all waiting to hear. Like Mary in the garden, we listen for “Rabboni”.

The Main Characters

But we don’t hear the Risen Lord or the fourth, missing tomb guardian. Its pages may be saturated with voices, but perhaps the loudest voice of all is that deafening silence which often preludes palpable faith or extreme doubt. Like a medieval onlooker, it felt as if I was observing the Quem quaeritis? (Whom do you Seek?) play being re-enacted on the page. The unnamed professor gazes in an obsessive manner and that everyman figure – the so-called friend – ventriloquises our own knowledge and ignorance into the imagined scene. We prompt the scholar. We distract her/him. It’s evident that we’re all entangled in an aimless gaze which never fully satisfies.

Purpose?

Miller, in his excellent review in the TLS, suggests that the primary purpose of the book appears to be philosophical: ‘it is about how an event becomes a story, a story becomes a myth, and a myth can be retrofitted by later events’. But this novel is much more than a philosophical exercise. Rowan Williams has praised Griffiths’ craftsmanship especially in the way that he weaves together ‘art history, psychology and theology, it invites us to think about imagination and truth, presence and absence […]’ And I would also add the thick threads of faith and doubt to that illustrious list.

To arrive at a primary purpose would be far too simplistic.

Without giving too much away, I even found the final pages of the novel moving. As readers, it’s tempting to find ourselves avoiding the significant but, as Williams notes in his summary, ‘not quite successfully enough to make [us] comfortable.’ It’s easy to over-think the purpose of a book like this. In what is, perhaps, an allusion to R. S. Thomas’ oeuvre, the lecturer concludes by describing the guardians like windows which have been over-polished by ‘so much looking’. This line reminded me of Thomas’ poem ‘The Small Window’ where a ‘crowd’ ‘dirty it / With their breathing’ or perhaps, in the Christian context, this vivid stanza from ‘Counterpoint’:

I have seen the figure

on our human tree, burned

into it by thought’s lightning

and it writhed as I looked.

The Passion and Resurrection have been thought so much about that the figure on the cross can no longer be separated from the wood in the speaker’s mind. Griffiths’ use of the word ‘polish’ also suggests one of Rowan Williams’ poems. In ‘The Stone of Anointing’, he writes:

And only when

the stone falls still will their tired polished

faces look back at them; ready to receive

Christ laid on them like a cloth.

These rich allusions are individual threads which are worth unpicking.

The Finished Piece

Like I said in the beginning, this is a layered book weaved on that threshold between faith and doubt. At the same time, it manages to be humorous, gripping, and energetic. The Tomb Guardians continue to sleep on the German pages which were manufactured near Munich. The artworks have been reproduced by the Henningham Family Press who, once again, prove that a published book can be a beautiful object. This is a well-crafted, highly readable book which deserves at least two readings. I can safely say (and even disagree with the speaker in another R. S. Thomas poem) that the ‘old stories are’ far from ‘done’.

The Tomb Guardians by Paul Griffiths is available now.

Nathan Munday is a regular Wales Arts Review contributor.