Wales Arts Review regular Carolyn Percy explores her love for the creator of Thunderbirds, and charts the remarkable story of his vision and success.

Fireflash, Terranian Airways’ Mach 6 atomic airliner, sabotaged on its maiden flight by a bomb placed in its landing gear. To land risks detonation and the atomic reactor powering the engines releasing radioactive material over a large area; if they stay in the air, the reactor’s safety shield will expire and all aboard will die from fatal radiation exposure. All efforts to try and dislodge or remove the bomb have failed. Fireflash appears to be doomed. Then, out of nowhere – a hope of salvation. International Rescue. Who are they? Where have they come from? The staff of the control tower at London Airport have no idea, but they’re Fireflash’s only hope. A rescue attempt is soon underway. Fireflash is ordered to approach with its landing gear up. International Rescue deploy their high-speed remote-control elevator cars, the flat elevated roofs providing a surface for the aircraft to land safely.

Fireflash approaches and the cars race into position. They align, Fireflash cuts power to its engines, lands, and the operator in the head car throws on the brakes. They screech, smoke beginning to rise from the wheels. Suddenly, the brakes on the head car blow, sending it spinning out of control until it flips over in the grass. The nose drops to the tarmac, sending sparks flying as the runway steadily runs out. Will they stop in time? Will the bomb detonate? Is the member of International Rescue in the flipped over car alright? All this plays out in front of a saucer-eyed four-year-old, whose mother, elsewhere in the house, is beginning to worry because, as all parents of small children know, quiet usually means they’re into mischief. That four-year-old, of course, was me.

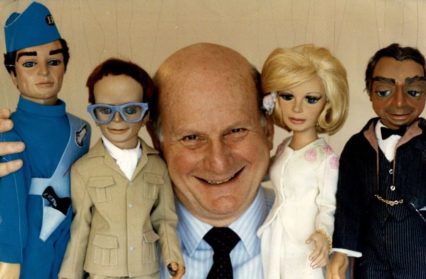

I’m sure many of you will have recognised the climactic scene from ‘Trapped in the Sky’, pilot episode of Thunderbirds, one of the many marionette adventure shows made by the late Gerry Anderson (if, like me, you’re especially nerdy, you’ll also know where the quote used in this article’s title comes from). An aspiring filmmaker whose dream was always to make live-action films, Anderson began his career, much to his chagrin, making puppet movies. In an effort to make the puppet film as ‘respectable’ as possible, Anderson, colleague Sylvia Thamm – who would become his wife & close collaborator until their divorce in 1981 – and their small production company would pioneer a way of filming that would not only result in a level of quality and sophistication not seen before in a family show, but also give birth to some of the most iconic series in the history of British children’s television.

But at the beginning of the 1960s, the future of AP Films was uncertain. They had already produced three series for independent television: The Adventures of Twizzle & Torchy the Battery Boy – made in collaboration with children’s author Roberta Leigh – and their own original creation, Four Feather Falls, a series set in the Old West, chronicling the adventures of Tex Tucker, sheriff of the eponymous town. They had all been well received, Four Feather Falls even making the cover of the TV Times. But the 60s was the decade that would come to be mythologised as the age of the future, and so, for their next project, that was what they looked to. In a secret laboratory in the Nevada desert, a team of people – two brilliant, eccentric scientists and their heroic test pilot – are developing a car. A car that can fly at incredible speeds, travel underwater and even into space, in other words: a Supercar.

But at the beginning of the 1960s, the future of AP Films was uncertain. They had already produced three series for independent television: The Adventures of Twizzle & Torchy the Battery Boy – made in collaboration with children’s author Roberta Leigh – and their own original creation, Four Feather Falls, a series set in the Old West, chronicling the adventures of Tex Tucker, sheriff of the eponymous town. They had all been well received, Four Feather Falls even making the cover of the TV Times. But the 60s was the decade that would come to be mythologised as the age of the future, and so, for their next project, that was what they looked to. In a secret laboratory in the Nevada desert, a team of people – two brilliant, eccentric scientists and their heroic test pilot – are developing a car. A car that can fly at incredible speeds, travel underwater and even into space, in other words: a Supercar.

By centering it around a futuristic vehicle, not only could they come up with more exciting and imaginative scenarios, they could also work around the limitations of the puppets – i.e. the fact they couldn’t be made to walk convincingly – to give their ‘acting’ the integrity to match the material. But an ambitious project requires money and therein lay the problem: Four Feather Falls had finished its run and Granada weren’t prepared to finance any more. They’d just about managed to keep their heads above water with some car advertisements and a low-budget live-action film, but the threat of bankruptcy was tangible.

Their last hope was Lew Grade, show business agent and co-head of ATV, a cigar chomping colossus who was changing the face of independent television. The meeting was reportedly a rather strange one. Anderson made his pitch, Grade showing cool detachment until it came to the cost: £3000 an episode. “Are you mad?” he exploded, “I can’t afford to make a show for that. Reduce that figure by half, then we’ll talk.” So, that night, Anderson went over the numbers again and again but was only able to reduce his costs by a third. He returned to Grade’s office the next day. “I’m sorry it’s not what you wanted,” he said, “but that’s my final figure.” Grade stood, implored Anderson for “just a minute” and walked through a door into what was presumably another office. After what must’ve felt like an age, Grade returned and said “Okay, you’ve got yourself a series.” And with that, not only were AP Films pulled back from the brink of financial ruin but a partnership was created that would allow a rocket-ship to erupt out of a swimming pool, a man to become indestructible and, eventually, for Luke Skywalker to become a Jedi and Superman to fly. This was the beginning of Supermaination. (Anderson would later discover that the room Grade walked into was not another office but a cupboard.)

I have my parents to thank for introducing me to the work of the Andersons. They can, of course, remember watching them when they first aired (whenever Four Feather Falls is mentioned, for instance, my dad’s first response is always to raise his arms and make gunshot noises in an impression of Tex Tucker’s magic guns). So when Supermarionation went through a renaissance in the early 1990s, beginning with Thunderbirds being re-aired on the BBC and released for the first time on VHS, they reasoned that, as they had enjoyed it as children, I might too, and bought me a video.

Now even if you’d never heard of Gerry Anderson before today (which, if you haven’t, firstly: shame on you, and secondly: what rock have you been living under?) you’ll almost certainly have heard of Thunderbirds. His most famous and, possibly, most popular creation recounts the adventures of International Rescue, a secret organisation founded by multi-millionaire ex-astronaut Jeff Tracy. Utilizing a raft of increasingly sophisticated vehicles and equipment, developed by stuttering chief scientist Brains and piloted by Jeff’s five sons – Scott, John, Virgil, Gordon and Alan – they are dedicated to rescuing lives in danger, particularly those others have failed or are unable to save. Two more important characters were British aristocrat Lady Penelope Creighton Ward and her lovable rogue of a cockney butler ‘Nosey’ Parker, secret agents who would help when needed. For even though there is a Britishness that runs through the very DNA of Anderson’s work, from the sense of humour to the Blue Peter-ish air of make and make do (sets, models and props were re-used in different combinations from series to series), because Grade was fixated on selling to the American market there was an American bias towards the characters – the Tracy brothers, for instance, were named for the Mercury Seven, a group of astronauts, including the late John Glenn, who were the forerunners to the Apollo programme – Lady Penelope and Parker were, in fact, the first British main characters since Supercar’s Dr Beaker and subsequently became not only two of the most popular characters in the show but in the whole Anderson canon.

That first episode captivated me and it’s difficult to say why & how exactly (I’d seen repeats of Watch with Mother before but, with all due respect to the beloved children’s character, Thunderbirds is about as far away from Andy Pandy as it’s possible to get) but I believe the best way I can put it is immersion: so much attention was paid to all the constituent parts, so that when they came together they created a consistent, fully immersive world.

Let’s start with the visuals and the technology used to create them. Firstly, the puppets themselves. Two things distinguish a Supermarionation marionette (a cheeky portmanteau of super, marionette and animation, coined by Anderson) from an ordinary puppet: a fibreglass head and a solenoid that, when placed inside the head, received electrical impulses sent along wires from a tape of pre-recorded dialogue that would move the mouth in time with the actor’s words, allowing for (theoretically) perfect lip synch. This, along with the later addition of interchangeable heads with different expressions, added a veneer of realism.

The same level of verisimilitude was applied to the rest of the visuals: models, sets and props were dirtied down to make them look used; practical effects (pioneered by special effects genius Derek Meddings, who went on to become an award winning special effects supervisor on the James Bond and Superman films), such as the rolling road and background – powered by motors but deployed at slightly different speeds, giving static models the illusion of movement – used to create the climactic Fireflash rescue, were filmed at high-speed, so that, when replayed at the standard twenty-four frames per second, the action was slowed down, giving them the illusion of mass, transforming modest fires and small splashes of water into raging infernos and crashing waves; the series directors also often used types of shot that were usually reserved for live-action photography (‘30 Minutes After Noon’ is a good example of this: an episode which uses a lot of experimental camera angles, including a brief shot of the action through a see-through clock face).

The same level of verisimilitude was applied to the rest of the visuals: models, sets and props were dirtied down to make them look used; practical effects (pioneered by special effects genius Derek Meddings, who went on to become an award winning special effects supervisor on the James Bond and Superman films), such as the rolling road and background – powered by motors but deployed at slightly different speeds, giving static models the illusion of movement – used to create the climactic Fireflash rescue, were filmed at high-speed, so that, when replayed at the standard twenty-four frames per second, the action was slowed down, giving them the illusion of mass, transforming modest fires and small splashes of water into raging infernos and crashing waves; the series directors also often used types of shot that were usually reserved for live-action photography (‘30 Minutes After Noon’ is a good example of this: an episode which uses a lot of experimental camera angles, including a brief shot of the action through a see-through clock face).

Then there were the stories. Anderson aimed his shows at a family audience and this was reflected in the writing: there weren’t any shoehorned morals, they simply concentrated on telling good, well-paced stories with no purpose other than to entertain. As Anderson himself said in an interview shown on BBC’s Newsnight: “It’s very simple: never second guess your audience. You do what you want to do, and if you find that the audience like what you want to do, you’ll be famous. And if they don’t like what you want to do, open a greengrocer shop.”

The stories were mainly plot-driven but good characterisation wasn’t sacrificed for this (barring the inevitable moments of 1960s sexism, Anderson’s female characters were pretty much on an equal footing with his male ones, occupying roles as diverse as doctor, engineer and fighter pilot without compromising their femininity or having that femininity reduce the importance of those roles – they did occasionally play the role of ‘woman tied to the train tracks’ – almost literally in Lady Penelope’s case – but this wasn’t their main or only function) and with no need to match mouth movements, the actors could give much more genuine performances (Scott Tracy was, and still is, my first TV crush – whether that’s sweet or sad I’ll leave up to you).

Obviously, there are elements that wouldn’t pass scientific scrutiny but that doesn’t matter, because everything made sense within the world of the show and corresponded to its own internal logic, and when this is the case you’re never pulled out of the story even if there are some things that don’t match real world logic.

And lastly, tying everything up in a nice big bow, is the music of Barry Grey: a gentle soul in a tweed suit with the voice of Alan Bennett, who composed all the music for the Anderson shows from The Adventures of Twizzle to Space:1999. Who doesn’t want to stride around the room the minute they hear the brass-band boom of the Thunderbirds march, or sigh along with the strings of ‘Aqua Marina’? But as well as being a great composer, Grey also knew when not to use music – many scenes have long stretches of no non-diegetic music, letting the dialogue convey all we need to know. So, when there was music, it always heightened what was going on screen.

After Thunderbirds, I moved on to Stingray and Fireball XL5 – the two shows that preceded it – with equal amounts of enjoyment. Then there was the show that followed it: Captain Scarlet. A colder, darker, more mature show, where, occasionally, the good guys didn’t win.

In the early 21st century, world security organisation Spectrum mans a mission to Mars. They discover a race of advanced, invisible aliens with the ability to reconstruct matter: the Mysterons. Misunderstanding leads to an altercation, resulting in a declaration of war against mankind and possession of the mission’s leader, Captain Black. Their first target: the World President. This leads to the death and subsequent possession of two more Spectrum personnel: Captain Brown and Captain Scarlet. Captain Scarlet is shot during the attempt however, and sent plummeting from the top of a London car park. Hours later, he returns to life, injuries healed, former personality intact and no memory of anything whilst under Mysteron control. Now rendered ‘virtually indestructible’, he becomes Spectrum’s key weapon in the ‘war of nerves.’ I never saw a whole episode of Captain Scarlet until I was eleven – when Supermarionation went through a second renaissance in the early 2000s. This wasn’t due to Donald Grey’s deep and scary ‘voice of the Mysterons’ or creepy Captain Black standing in a fog-filled graveyard. Oh no, I never even got that far.

In the early 21st century, world security organisation Spectrum mans a mission to Mars. They discover a race of advanced, invisible aliens with the ability to reconstruct matter: the Mysterons. Misunderstanding leads to an altercation, resulting in a declaration of war against mankind and possession of the mission’s leader, Captain Black. Their first target: the World President. This leads to the death and subsequent possession of two more Spectrum personnel: Captain Brown and Captain Scarlet. Captain Scarlet is shot during the attempt however, and sent plummeting from the top of a London car park. Hours later, he returns to life, injuries healed, former personality intact and no memory of anything whilst under Mysteron control. Now rendered ‘virtually indestructible’, he becomes Spectrum’s key weapon in the ‘war of nerves.’ I never saw a whole episode of Captain Scarlet until I was eleven – when Supermarionation went through a second renaissance in the early 2000s. This wasn’t due to Donald Grey’s deep and scary ‘voice of the Mysterons’ or creepy Captain Black standing in a fog-filled graveyard. Oh no, I never even got that far.

A brief burst of music that soon spindles away to almost subliminal levels, footsteps echoing down a dark and empty alleyway, the unseen end coming ever closer. Suddenly, a cat screeches and torches flash, illuminating a man in a scarlet uniform. Bullets fire but the man is unharmed. He raises his gun, fires a single shot, and with a final grunt, his assailant falls down dead.

This opening had a similar effect on me that many – my mother included – claimed the Doctor Who theme had on them, and terrified me so much I was unable to watch any further. (The ending theme, however, allowed for some inappropriate hilarity when, halfway through the run, they put lyrics to what had previously been an instrumental: “…they smash him, and his body will burn/They crash him, but they know he’ll return, to live again!” accompanied by beautiful comic style illustrations of Captain Scarlet drowning in a swamp, falling off a building, being crushed by rocks whilst trying to reach for a lit stick of dynamite etc. Murder and mayhem by the way of Benny Hill.)

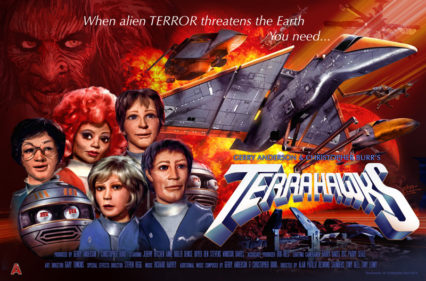

If Thunderbirds was the pinnacle, then Captain Scarlet was the last of a golden age. Two more Supermarionation productions followed: Joe 90 and the bizarre puppetry/live action hybrid starring Stanley Unwin, The Secret Service, which Grade cancelled after only thirteen episodes. The era of Supermarionation was over, and Anderson moved on to what he’d always wanted to do: live action – only, tragically, to find that others had taken the ideas and techniques he’d pioneered and left him behind. In the world of live action, he was no longer unique. He made a return to puppetry in 1983 with Terrahawks – this time using Jim Henson style puppets that were operated from beneath, dubbed ‘Supermacromation’ – which, despite Anderson going on record with the fact it wasn’t his favourite creation, was still incredibly popular at the time and maintains a cult following to this day.

If Thunderbirds was the pinnacle, then Captain Scarlet was the last of a golden age. Two more Supermarionation productions followed: Joe 90 and the bizarre puppetry/live action hybrid starring Stanley Unwin, The Secret Service, which Grade cancelled after only thirteen episodes. The era of Supermarionation was over, and Anderson moved on to what he’d always wanted to do: live action – only, tragically, to find that others had taken the ideas and techniques he’d pioneered and left him behind. In the world of live action, he was no longer unique. He made a return to puppetry in 1983 with Terrahawks – this time using Jim Henson style puppets that were operated from beneath, dubbed ‘Supermacromation’ – which, despite Anderson going on record with the fact it wasn’t his favourite creation, was still incredibly popular at the time and maintains a cult following to this day.

The periodical resurgence of interest in Supermarionation has led to some good things – a new CGI series of Captain Scarlet in 2005 – and some not so good – such as the 2004 live action Thunderbirds film which was… disappointing – but all the while Anderson kept working, always looking to the future, always looking to the next project; even the crushing blow of being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s didn’t stop him. But, sadly, that couldn’t last forever, and on December 26th 2012, Anderson lost the battle and died aged 83.

So, are we just left with the shows and the memories? Not so. In 2015, not only was there the start of a new Terrahawks audio series but – as a result of a co-production between ITV and Pukeko Pictures (a New Zealand based animation studio responsible for many of the effects of the Lord of the Rings and Hobbit films) a new series of Thunderbirds!

Thunderbirds Are Go (not to be confused with the 1966 film), now halfway into its second series, combines CGI characters with live models and sets. And whilst I’m not going to list and compare the similarities and changes made due to 50 years’ worth of cultural and technological advancement (a subject, I feel, for another article entirely) it’s safe to say it successfully embodies the spirit of the original. With this and three overwhelmingly successful Kickstarter campaigns – one that realised Anderson’s last project – Gemini Force One – as a series of children’s books, another which led to the creation of three new ‘original’ Thunderbirds episodes (dubbed Thunderbirds 1965, which used mini albums recorded in the 1960s to lay down the audio and dialogue and were made by recreating many of the original filming and production techniques, from making sure the episode titles were in the correct font to treating the film to make it resemble 1960s film stock) and, lastly, one which will hopefully lead to a new puppet series (where Supermarionation has now evolved into ‘Hypermarionation, with puppets that are controlled by rods to allow for a greater spectrum of movement and servos that allow the facial features to move) the future for Anderson fans looks very bright indeed.