There is an idea of a Patrick Bateman, some kind of abstraction, but there is no real me, only an entity, something illusory, and though I can hide my cold gaze and you can shake my hand and feel flesh gripping yours and maybe you can even sense our lifestyles are probably comparable: I simply am not there.

– American Psycho by Bret Easton Ellis, pub. March 1991

Patrick Bateman has a fastidious grooming regime. Should we be following it?

– Men’s lifestyle website, ‘Mr Porter’, December 2013.

By his own admission, Bret Easton Ellis was sick during the period when he wrote American Psycho; sick of his own success, sick of America, sick of himself. Newly relocated to New York, aged just 23, alone and confused: ‘I was trying to fill up my unhappiness with the yuppie culture and buying things, and going out to nice restaurants. And then being enraged that it wasn’t working. It was my pain that was interesting to me; the rest is fantasy, and the novel stemmed out of that.’ And what a novel. A master-class in misanthropic Manhattan satire on a par with The Bonfire of the Vanities, or (depending on who you speak to, and at what point in the passage of time) a self-indulgent, amoral exercise in ill-focused and spectacular violence; the misogynist’s bible. Notwithstanding, it is a text that has since spawned a successful cinematic reworking that now represents the commercial entry point for many of the book’s newest readers, an incongruous and lucrative side-line in fan-boy action figures, and most recently an ambitious and headline-grabbing musical adaptation at London’s Almeida Theatre; a development all the more newsworthy for its casting of outgoing Dr Who, Matt Smith, as the diabolical anti-hero Patrick Bateman.

By his own admission, Bret Easton Ellis was sick during the period when he wrote American Psycho; sick of his own success, sick of America, sick of himself. Newly relocated to New York, aged just 23, alone and confused: ‘I was trying to fill up my unhappiness with the yuppie culture and buying things, and going out to nice restaurants. And then being enraged that it wasn’t working. It was my pain that was interesting to me; the rest is fantasy, and the novel stemmed out of that.’ And what a novel. A master-class in misanthropic Manhattan satire on a par with The Bonfire of the Vanities, or (depending on who you speak to, and at what point in the passage of time) a self-indulgent, amoral exercise in ill-focused and spectacular violence; the misogynist’s bible. Notwithstanding, it is a text that has since spawned a successful cinematic reworking that now represents the commercial entry point for many of the book’s newest readers, an incongruous and lucrative side-line in fan-boy action figures, and most recently an ambitious and headline-grabbing musical adaptation at London’s Almeida Theatre; a development all the more newsworthy for its casting of outgoing Dr Who, Matt Smith, as the diabolical anti-hero Patrick Bateman.

The cultural wind blows in unexpected and mysterious ways, and whilst it may have circled the author like a predatory cyclone in the early 1990s, time, context and the forces of artistic reappraisal have been kind to both Ellis and his core vision. As Ellis recalled upon the novel’s twenty year anniversary:

Whenever I am asked to talk American Psycho, I have to remember why I was writing it at the time and what it meant to me. A lot of it had to do with my frustration with having to become an adult and what it meant to be an adult male in American society. I didn’t want to be one, because all it was about was status. Consumerist success was really the embodiment of what it meant to be a cool guy — money, trophy girlfriends, nice clothes, and cool cars. It all seemed extremely shallow to me. Yet at the same time you have an urge to conform. You want to be part of the group. You don’t want to be shunned. So when I was writing that book as a young man, I was having this battle with conforming to what was then yuppiedom — the yuppie lifestyle — going to restaurants and trying to fit in. I think American Psycho was ultimately my argument about this.

Given this telling and resonant personal reflection, it feels wholly appropriate to have launched American Psycho – The Musical in London, rather than in the more anticipated environs of Patrick Bateman’s Broadway. It may have taken over two decades to have finally succumbed to the pressure of Bateman’s steely grip, but it’s hard to dispute that in 2013, a London presided over by the sinister, ‘Keystone Cops’ autocracy of Boris Johnson is finally sleepwalking its way towards its own American Psycho moment. In the shadow of metropolitan food banks, and with the backdrop of an ever more lawless ‘city boy’ culture – the people who almost torched the planet, let’s not forget – the musical’s sponsor, men’s lifestyle website ‘Mr Porter’, sees little absurdity in appropriating the preposterous antiseptic veneer of Ellis’s work from the contextual repulsion at its core: ‘From exfoliating to moisturising to clarifying, it would be fair to say that Bateman is no shirk when it comes to scrubbing up. And while we wouldn’t recommend adopting his approach to looking your best word for word (let’s not forget the novel was intended to parody rampant 1980s consumerism), there’s something slightly awe-inspiring about a grooming regime that leaves no stone unturned in the search for perfection. To that end, we have pored over the original text and highlighted the parts worth incorporating into your morning routine – with a MR PORTER twist.’ ‘Awe-inspiring’, ‘perfection’; words that appear freshly plucked from the neurotic self-obsession of Bateman’s inner torment, the appropriation and relocation of morally bankrupt 80s New York yuppie culture by a 21st century city in thrall to an all-pervading culture of possession, exploitation, and personal dissatisfaction; capitalism’s crushingly grinding victory over the forces of joy and artistry. To quote Phil Collins, a notorious favourite of Bateman – his ‘emotional honesty’ – and a song that plays a key role in the book’s musical adaptation: ‘I can feel it coming in the air tonight / Oh Lord’.

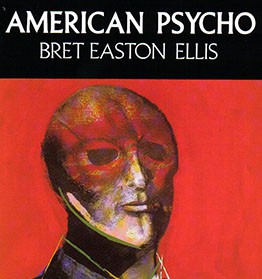

American Psycho’s emergence into the world was almost as troubled as the mind-set of its narrator, a trauma played out under the scrutiny of publicity and moral panic. Simon and Schuster refused to publish the novel at the last minute, allowing Ellis to stroll off with his alleged $300,000 advance in a Sex Pistols-mirroring pillage of Malcolm Mclaren-esque proportions. The publisher claimed editorial objections; Ellis claimed that they feared commercial reprisals. The influential Spy magazine had just written a castigating article about Bateman’s fondness for the violent brutalisation of prostitutes, the LA branch of the National Organisation of Women famously branding the work: ‘a “how to” novel on the torture and dismemberment of women’. Though the threat of boycotts of any potential publisher remained, a division of Random House purchased the book for Vintage, defending its decision on the grounds that Ellis’s novel was, above all, ‘serious’. Upon its release, its cover art a bleak collision of Armani suit and faceless death-mask, the book’s initial reviews – in the shadow of protest, partly as a result of protest – stunk the place out. Ellis was box office B.O. as far as the world of literacy criticism was concerned, and although there were isolated instances of praise, most notably Fay Weldon’s Washington Post appraisal of American Psycho as a ‘beautifully controlled, important novel’, his creation was elsewhere derided as ‘sensationalist’, ‘brutish’, and in what was no doubt the real stake to the author’s heart, ‘numbingly boring’.

The extremity of the book’s content, whilst both graphic and uncompromising, should have come as only a momentary shock to followers of the author’s career up to that point. His previous novels, Less Than Zero, and The Rules of Attraction had already explored the mental and physical brutality exacted by a narcissistic generation of over-privileged, under-enthused American youth obsessed solely with the veneer and surface of things. Psycho was a mere extension of these previously explored themes, and though its content undoubtedly ratcheted up the horror, its core themes barely strayed from the thematic pattern set by his earlier works, a literary template that had seen him swiftly bracketed alongside fellow 80s wunderkinds Jay McInerney and Tana Janowitz. What the book undoubtedly wielded in abundance was a heaving sack of soot-black humour that both alleviated and intensified the anxiety in equal measures. Aside from Bateman’s aforementioned obsession with personal grooming and his militaristic cosmetic rituals the abiding experience for many of Ellis’s book – a series of lengthy passages further brought exquisitely to life within Mary Harron’s cinematic adaptation – is the character’s notoriously anodyne taste in 80s pop music, the joyless dissection of his insipid preppie tastes in absurdly granular detail. A process recollected by the author in an interview with askmen.com: ‘When I was writing American Psycho I felt like I was writing an epic issue of a men’s magazine. It was about grooming products and fashion and restaurants. It was about sex and a guy’s girlfriends, and it needed reviews.’

This writer’s sole meeting with Ellis, during a UK promotional tour for his belated, flawed, follow-up book, The Informers, was not immune from the inevitable questions about his most notorious creation’s predilection for Huey Lewis and the News and late-period Genesis. Adopting a momentary tone of mock affront, the author faced me down with his most stoic poker face, his voice tinged with disbelief and indignation: ‘You mean to say you think those bands are shitty?’ Ellis has always been good at holding the tension, and the subsequent period of cultural reappraisal that has seen the book emerge from the shadows as a latter-day classic has been a slow and interminable one. For his own part, the author has consistently refused to act as either an opportunistic revisionist or a mealy-mouthed apologist for his artistic vision, taking the view that much of the revulsion about the book’s supposed content was one ultimately skewed by the cultural dead-end of received wisdom. Almost unthinkable in 1991, American Psycho has subsequently become a personal and important feminist text for many. Ellis again: ‘With all that controversy describing hundreds and hundreds of pages of torture and death and blood and this is what people were expecting from the book. People started to talk about the book, and they also started to talk about how funny it was — when I was writing the book I remember thinking it was a black comedy. It’s like 400 pages of social satire and people eating in restaurants and the guy with the various women in his lives and whatever. And its reputation began to change. The movie version helped change the reputation, too. And it all changed to the point that American Psycho is now considered an acceptable part of the culture.’

‘As soon as I started reading it, it was completely obvious to me that it was a satire – a critique, not an endorsement’

– Mary Harron, dir. American Psycho (2000)

Whether the producers of the film adaptation of American Psycho sought out the services of Mary Harron as a direct result of her directorial debut at the helm of the Valerie Solanos biopic I Shot Andy Warhol, or more for her reputation as a strident and outspoken feminist is unlikely to ever be conclusively answered. What is not up for debate is the presentational shrewdness of the choice, something acknowledged even by the director herself. Rather than being put off by the violence, Harron’s main concern was that it might prove ‘unfilmable’: ‘the book is very stylised, and abstract. How you do that on film doesn’t simply jump off the page.’ Branded ‘the most disgusting film ever made’ prior even to its release, the film’s troubled gestation was even more problematic than the initial release of Ellis’s book. Harron initially resigned in protest as a consequence of the desire of the then-teen idol Leonardo DiCaprio (originally cast as Bateman) to make the character somehow more humane, and less of a psychopathic killer. The director only returning to the project with the newly re-cast lead – Welshman Christian Bale – once DiCaprio bailed, a victim of the intense lobbying of his team of advisors who saw little commercial value in their Titanic-era matinee idol being seen tearing down the stairwell of an apartment block, naked, blood-spattered, and wielding a chainsaw. For his own part, Bale took to the project with a personal intensity that would later play out to an acute ‘method’ extreme in 2004’s The Machinist. Using the dead-eyed ‘Martian-like’ Tom Cruise by way of inspiration Bale spent numerous months in thrall to an intense personal training regime to achieve the appropriate level of narcissistic physical perfection. Proof-positive of Bale’s inner Welshman is the regret that he has since spoken of regarding the cosmetic dentistry work he was coaxed into undertaking on the road to ‘becoming Bateman’: ‘When I did American Psycho I did fix my very British teeth, which I miss dearly. But Bateman couldn’t have had the teeth I had. I kept a mould of my old ones because I did like them and I knew I’d miss them.’

In a world that had yet to experience the questionable visceral intensity of The Human Centipede the supposedly ‘unfilmable’ nature of the story formed the underlying narrative of the cultural commentary that co-existed throughout the production of American Psycho. Yet upon its release, many critics seemed perversely disappointed by the absence of blood-lust from Harron’s work, at its failure to succumb to the clichéd ‘slasher’ genre that could so easily have been its straight-to-video fate. That Harron had proved to be the antithesis to Michael Winner may have initially disappointed the rock band roadies whose copies of Ellis’s text were routinely creased at spine-breaks marked ‘the brain’, ‘the rat’, but would ultimately prove to be the film’s enduring salvation. Harron’s work mines deeper the seams of Bateman’s raw vulnerability: his total absence of self-awareness, his self-loathing, the everyday potential for male violence and the brutality of capitalism. The now iconic ‘business card’ scene has completely transcended its original source material and has since entered the cultural lexicon as the embodiment of yuppie stupidity. From the very first scene of a blood-red raspberry coulis being ceremoniously dripped onto an essentially empty plate of fraudulent nouvelle cuisine, Harron’s film proves itself to be a masterwork of restrained authority, one of the smartest and most clinically efficient films of the 21st century. As a foreboding portent of the disposability and vulnerability of humanity, a scenario that would come to fruition beyond the collapse of the world financial markets in 2008, it has no peers.

‘Am I just a version of the end of days?’

– ‘This is Not an Exit’ – American Psycho, the Musical

When Matt Smith emerges vertically from the depths of the Almeida’s stage, on a sunbed, in his underwear, it is immediately apparent that he has taken some tough lessons in physical narcissism from his cinematic predecessor. For many, the prospect of a musical based on Ellis’s book and Harron’s film (for this production appropriates elements of both) was an artistic stretch too far. Yet any doubts about the motivation or cultural value of this production are swiftly erased. Smith – detached, vacant, and utterly devoid of personality (as any good Bateman should be) – makes an excellent fist of swiftly sucking the audience into his personal realm of paranoia, his rapidly collapsing house of cards. In doing so, he triumphantly succeeds in perhaps the most brutal, bloody murder of them all, the ritualistic slaying of the biggest elephant in the room; his iconic bow-tied incarnation of The Doctor. Yet prior to this current production the only song that had ever been recorded in honour of American Psycho was Manic Street Preachers execrable ‘Patrick Bateman’ a song so clumsily poor that the Manics themselves have since seen fit to purge their musical CV of its very existence. Thankfully, this adaptation seeks to swerve the ‘Broadway’ approach to business, opting instead for a brooding Giorgio Moroder-influenced set of songs broadly rooted in the disconnected melancholic style of the final act of The Rocky Horror Picture Show. Much like Rocky himself, a character who is also introduced to the audience in a tiny pair of underpants, the ultimately doomed nature of Bateman, his friends, his entire generation is writ large from a very early point in proceedings. ‘The Musical’, much like the film, places notable emphasis upon it’s narrators propensity for fantasy, a delusional nature so extreme that the audience is challenged to question whether anything he says, or does, or slays is even true, or simply a figment of his twisted imagination. As if, to echo the text of the book, he simply is not there.

A scene that plays out consistently across Ellis’s book and its subsequent cinematic and theatrical adaptations is the icily cruel slaying of a homeless man on a deserted Manhattan street. An apparent embodiment of the character’s fear and revulsion of the dispossessed and disenfranchised, the societal counterpoint to the pristine veneer of his Wall Street theme park existence; a sensation of antipathy bordering on hatred for a fellow human being, one based on little more than ignorance and fear. Later that night as I walked along Islington’s Upper Street, from the Almeida to the nearby underground station I passed by a couple stepping silently and unhesitatingly over the prostrate body of a huddled homeless man and his dog who were blocking the entrance to their flat. A woman’s key forced firmly into a door, her companion ushering her swiftly up a staircase. As if the man, his dog, his pitiful existence were of no consideration or consequence. As if he simply was not there.

Illustration by Dean Lewis