Steph Power attended Gloucester Cathedral to witness a performance of Elgar, Sibelius and Rachmaninoff as part of the Three Choirs Festival 2013.

Edward Elgar – In the South

Jean Sibelius – Luonnotar

Sergei Rachmaninoff – The Bells

Conductor: Vladimir Ashkenazy

Soprano: Helena Juntunen

Tenor: Paul Nilon

Baritone: Nathan Berg

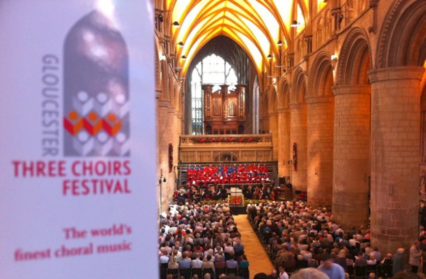

Hereford, Worcester and Gloucester may lie firmly beyond the ‘Land of Song’, but the excellence of their cathedral choirs and the passion for amateur and professional singing evident across their counties serve as a reminder that – in present-day choral terms at least – that particular cultural cliché can be overworked. Alternating annually between each cathedral, the Three Choirs Festival is one of the longest running choral events in the world. This year, it celebrated its 286th birthday in Gloucester with the usual emphasis on tradition and, in 2013 at least, with cautious nods to the new; the latter represented most extensively by Arvo Pärt – a composer now so ubiquitous in UK programmes that even the most musically risk-averse of Three Choirs regulars must surely be familiar with his music.

It goes without saying that there would be no such questions of recognition regarding Edward Elgar, the Festival’s dominating force for much of the twentieth century and continuing to the present day. A Roman Catholic outsider from rural Worcestershire, Elgar rose after many years of struggle, not merely to be embraced by the English establishment, but – however improbably in more subtle ways – to define it in the eyes of many. For Adrian Partington, the Three Choirs’ Artistic Director (and, incidentally, the long-standing Chorus Master at BBC National Chorus of Wales), Elgar ‘is still, and probably will remain, the essence of the Festival’ and the composer was duly honoured throughout the eight days of music-making; not least, with a thrilling opening gala performance of his concert overture In the South (Alassio) Op. 50 by the Philharmonia Orchestra under its esteemed conductor laureate Vladimir Ashkenazy.

Elgar’s single-movement piece was conceived and largely written whilst on holiday to Northern Italy in 1903-4 and is one of his least complicatedly exuberant. Indeed, it came at a high point in his career, when his acceptance into society was about to be made publically unequivocal; the March 1904 London Festival at which In the South would be premièred was devoted solely to Elgar’s music – an unprecedented stamp of approval for an English composer – and he was elevated to a knighthood later that year. Regarding tonight’s programme, I had a slight concern that the opening placement of the piece would be as a crowd-pleaser before Ashkenazy got down to business with his specialisms of Sibelius and – especially – Rachmaninoff (I agree with Mark Elder, for instance, who believes that In the South is really more substantial than a concert overture and should be accorded the significance of a symphonic poem rather than treated always as a programme apéritif). But I needn’t have worried. Ashkenazy’s terrific rendition not only opened the concert (and the Festival) with panache, but it made plain the true stature of the piece.

The big, warm sound for which the Philharmonia is famous came into its own from Elgar’s extrovert, Straussian beginning, with Ashkenazy clearly relishing the score’s broader phrases, without neglecting the textural contrasts and many fine timbral details – and without slipping into sentimentality. Beautifully incorporating the extended reverie of the solo viola serenade (lyrically played by Rebecca Chambers), this was a fullsome, entirely unbombastic, performance which lived up to David Owen Norris’s observation that ‘very little of what this music is about is on the surface’; something which I believe to be true of much of Elgar’s music, in stark contrast to the jingoism with which it is so often misguidedly associated. Particularly stunning tonight was the cyclic ‘descending fanfare’ so to speak, of intervals dropping by fifths, in Elgar’s depiction of imagined Roman legions crossing a viaduct near his holiday home. This was spine-tingling in the cathedral and will resonate long in my memory.

In some ways, the Elgar was actually the highlight of the evening, as the bold, lush orchestral colours filled the cathedral with no added voices to bring further balance issues into the reverberant space. The other two programme items suffered at times in this regard – although there was no gainsaying the sheer quality of musicianship on offer. Central to proceedings were two centenary celebrations; the first having special significance for the Three Choirs in the form of Luonnotar (Op. 70); Jean Sibelius’s short masterpiece, which was commissioned by the Festival and premièred there in 1913. This is a wonderfully beguiling work which Sibelius composed between his Fourth and Fifth Symphonies and which hovers between worlds on many levels; from its ethereal soundscape, oscillating between light and dark colouration on the edge of tonality, to its deep, organic phrase structures that point to the radical architectural techniques Sibelius would shortly come more fully to embrace. Again, Luonnotar (that is, in the orchestral version – the piece also exists as a song for soprano and piano) hovers between solo ‘cantata’, orchestral song and symphonic poem. The supposed strangeness of its soundworld, together with the tremendous difficulty of its vocal line, led to the piece being neglected for many years – arguably until the very same magical combination of Ashkenazy and Philharmonia, with the sorely missed Elisabeth Söderström, threw down the interpretational gauntlet in the late nineties. The high tessitura is challenging enough, but the Finnish text, taken from the mythological epic Kalevala, sadly still deters many non-Scandinavian sopranos from attempting the part.

Tonight’s soloist, the Kiiminki-born Helena Juntunen, amply demonstrated her vocal prowess as well as her Sibelian expertise. From ghostly floating over sustained strings to fearsome major-minor ambivalence, soprano and orchestra together were spellbinding throughout, with some fine sectional blending – particularly between brass and woodwind – adding to the heightened atmosphere. However, notwithstanding Juntunen’s expressive intensity, there was some irony in the words themselves becoming lost in the acoustic, as Sibelius’s setting of this ancient, decidedly Finnish, text can be seen as part of his ongoing effort to assert Finland’s right to its own culture and national independence against the Russian domination that had prevailed in his country for over a hundred years.

Finland was at last able to claim independence from Russia after the Bolshevik Revolution there in 1917. Around that time, many Russians of the old aristocracy fled the Motherland into exile after the Communists took control. Among them was Ashkenazy’s elder-countryman Sergei Rachmaninoff; a composer with whom the celebrated pianist and conductor has, of course, enjoyed a long and distinguished association. Tonight’s performance of The Bells (Op. 35) – as might be imagined – was spectacular. Also written in 1913 (the same year, too, as Rachmaninoff’s fellow-exile and aesthetic opposite Igor Stravinsky produced his (in)famous Rite of Spring, which centenary celebrations are surely inescapable this year), Rachmaninoff also referred to it both as his ‘Choral Symphony’ and his ‘Third Symphony’; that is, until he composed a purely instrumental Symphony No. 3 in 1935-6.

Whatever the designation, The Bells is possibly the greatest of Rachmaninoff’s secular choral works. Coincidentally, like tonight’s Elgar, it was composed during an Italian holiday, after Rachmaninoff received a copy in translation of the poem in four sections by Edgar Allan Poe from which the piece eventually took its name. Having loved the sound of Russian church bells since he was a child, and inspired by the poem’s darkening sweep from youth to old age, he now set to work in the same Roman apartment that his revered forbear Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky occupied in earlier times – the mournful ending of whose Sixth Symphony ‘Pathétique’ inspired Rachmaninoff’s own death-shrouded finale. Tonight, the combined forces of Philharmonia and Festival Chorus were magnificent, with Ashkenazy seeming to conduct from inside the sound itself to produce a performance of elemental power. Of the three soloists, Juntunen again proved immensely impressive (if not so dark-hued as I personally would favour), whilst baritone Nathan Berg exuded charisma and melancholic intensity in equal measure. Alas, the undoubtedly fine tenor of Paul Nilon – from where I sat at least – was too easily overwhelmed by the huge forces of chorus and orchestra.

Overall however, the glories of this performance were many; from the rich, deep-piled carpet so to speak, of the Philharmonia’s lower strings to the exquisite bell-like sonorities – so beloved of Rachmaninoff – in ringing brass, woodwind, and indeed, percussion; from the tight, rhythmic energy of the third movement Presto, palpable despite the cavernous acoustic, to the achingly desolate cor anglais of the final Lento lugubre (played with moving simplicity by Jill Crowther). Rachmaninoff often referred to The Bells as a favourite among his own works. Contrary to his reputation and the scowl familiar from certain photographs, his was a melancholic rather than a tragic disposition, and the orchestral coda to his choral symphony does seem to suggest some hope within the mournful scene.

It would be fascinating to see for which composer the cathedral bells might ring in celebration rather than valediction a hundred years from now at the Three Choirs Festival. In terms of commissions, Luonnotar was a major contribution to the then international contemporary scene (although fortuitously so – the Festival had actually commissioned a choral piece from Sibelius, as might be expected from a choral festival, but it never materialised) and the piece has now, at last, begun to be accorded the recognition it deserves. This year, there were welcome new works from John Hardy, Torsten Rasch and John O’Hara – but we will have to wait until next year for a major new commission from the Festival. That will appear in the form of Torsten Rasch’s projected work A Foreign Field (Echoes 1914) in commemoration of both World War I and the destruction of Chemnitz by Allied bombing in World War II; an important première in a year which will no doubt see many heart-felt such commemorations.