Cardiff University’s film festival, Unfinished, will run from 17th – 20th November 2022 at Chapter Arts Centre, and will celebrate the determination and dedication of women filmmakers across the world. Featuring unfinished, incomplete and fragmentary works, this festival seeks to magnify women’s cinematic voices in the face of limited finances, pressures on time, and, in some cases, active attempts at silencing. Here, Philippa Fincher takes a look ahead at what to expect from the festival, and shines a light on some of the women the festival will showcase.

In their 2016 article exploring found footage and the way women strive to create cinema, feminist film scholars Monica Dall’Asta and Alessandra Chiarini describe “women’s tenacious will to make cinema at all costs . . . under conditions of limitation and lack of means”. This tenacity and determination, and the range of creative outputs that result from it, are the focus of Cardiff University’s upcoming film festival, Unfinished. This festival explores the aspirations and ambitions of filmmakers, and the practical, economic and cultural realities that impact film production.

The festival organisers, Dr Alix Beeston (Cardiff University) and Dr Stefan Solomon (Macquarie University, Australia), are focusing on unfinished films as part of a feminist mission to recover and recentre filmmakers and projects which have been marginalised in film history. But more than this, they seek to explore how practical limitations, restrictions, and marginalisations can allow some filmmakers to pursue fragmentation, incompletion and ‘unfinishedness’ as deliberate, creative choices. As Beeston and Solomon write in the festival programme: “To be unfinished is to be in process”

The films shown in this festival are unfinished for a variety of reasons: illness, death, displacement, censorship or loss of funding. The works of two filmmakers, Jocelyne Saab and Sandi Tan, particularly exemplify “women’s tenacious will to make cinema at all costs”. Their works, though incomplete and fragmentary, were created in defiance of active attempts to silence them.

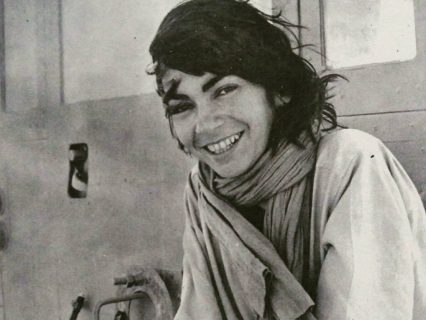

Lebanese activist filmmaker Jocelyne Saab was a director whose works explore social and political issues, with a focus on subjects such as soldiers in exile, war-torn cities, and displaced people. Fluid and flexible, her creative style was well able to handle the complexity of the issues she explored. She was a storyteller who embraced unfinishedness, evolution, fragmentation, and change in her cinematic works.

Three of Saab’s works will be shown on Saturday 19th November at 4pm: My Name is Mei Shigenobu (2018); Les femmes Palestinnienes (Palestinian Women, 1973); and Le Liban dans le tourmente (Lebanon in a Whirlwind, 1975). Dr Mathilde Rouxel, a world-leading expert on Saab’s films and Saab’s assistant during the last ten years of her life, will present the films and lead a post-screening discussion.

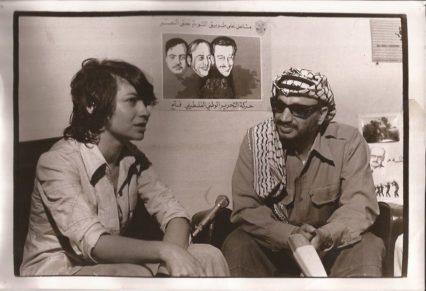

Saab began her filming career as a war reporter for French television. It was in this role that she filmed Palestinian Women, a report on Palestinian women in Lebanon and their cultural and armed resistance of Israeli forces in the country. She interviewed many women in refugee camps and in universities, giving voice to an often-ignored group, and as a result, offered a unique, intimate, and feminist examination of the Palestinian people at the time.

However, the French media refused to screen this report, which remained ‘unpublished’ until after her death in 2019. Saab viewed this suppression as censorship, as an act of silencing violence. In so doing, Saab became an independent filmmaker, taking control of her own cinematic and creative voice. In 1975, at the beginning of the Lebanese Civil War, she filmed her first feature length documentary, Lebanon in a Whirlwind. In this rich, multifaceted piece, Saab attempted to showcase many different perspectives of the conflict, while demonstrating the violence that was ripping through her country. This proved a dangerous project for Saab and her crew, who were attacked by members of a Christian political group and militia, the Phalangists, while filming. Her camera was broken and much footage destroyed. In defiance of such violence and attempts to silence or stop her, Saab completed the documentary, which was screened in cinemas in Paris.

Saab was a filmmaker determined to tell stories of the deprived, disadvantaged and displaced. Her clear and defiant cinematic voice rang loud, despite attempts at censorship and silencing, and now, the Unfinished festival provides further amplification for this remarkable filmmaker.

Building on the opportunity to showcase pioneering work which defies censorship or other forms of refusal, Unfinished will also feature the work of Sandi Tan. Tan, a Singapore-born filmmaker, began her career aged 19. With her friends and fellow filmmakers, Jasmine Ng and Sophia Siddique Harvey, Tan filmed Shirkers in the summer of 1992, with the help of an older man named Georges Cardona. Shirkers, written by and starring Tan herself, was to be a road movie, focused on 16-year-old serial killer, S, and her travels around the small island of Singapore. It would have been the first of its kind produced in the country; as Tan proudly states in the film, the group were “pioneers”.

However, this germinal, quirky, indie road movie would never exist in its intended form. After weeks of tireless shooting, all 70 rolls of film vanished. The young women’s hard work was stolen by Georges Cardona, the mysterious man they had believed was their mentor, their friend. We can see Cardona’s theft as an attempt to erase and silence the creative voices of three young female filmmakers. Indeed, Tan highlights her inability to talk about the original Shirkers, in the years following shooting. She states that she would say “no to interviews asking [her] to talk about Shirkers” and that she was unable to write a book about it when offered a published deal to do so.

Tan, Ng, and Siddique all made multiple efforts to regain their film, but Cardona ignored them, keeping this creative project silent. Shirkers was lost for nearly 20 years, but then it was returned to Tan by Cardona’s wife in 2011, following his death. The Shirkers that exists today was completed in 2018. Tan has pieced together the fragments of ‘what should have been’ into a feature-length documentary, chronicling the creation, loss, and recreation of the young women’s collaborative work. It is a fragmentary film, haunted by the spectre of Georges Cardona, as well as by the glimpse of the Shirkers that never was—and the youthful passion and enthusiasm of Tan, Ng and Siddique.

The 2018 Shirkers is a feminist act of reconstruction. Cardona may have attempted to erase the work and silence Tan’s cinematic voice, but by recreating and revising the project, she has taken control of the narrative. She regains her voice to tell her story of the Shirkers project. In an email to myself, Siddique celebrates the “generative and creative possibilities” of the returned Shirkers film reels, as it allowed for the creation of a new soundscape, and experimentation with temporality. The inclusion of Shirkers (2018) in Unfinished is a doubled act of feminist recovery; Tan and her friends’ project is placed in cinematic history, where it belongs, and their silenced cinematic voices are amplified.

Shirkers will be screened on Friday 18th November at 8pm, with Sophia Siddique introducing the film in person and answering audience questions.

Both Jocelyne Saab and Sandi Tan are bold directors and cinematographers. Their works speak loudly, prevailing against attempts to silence them, defiant against attempts to stop or erase them. They exemplify “women’s tenacious will to make cinema at all costs”. The Unfinished film festival will lend them further amplification, honouring their passion, ambition, determination to create cinema no matter what.

Free tickets for all Unfinished sessions are available via Chapter’s website. The festival runs from 17th-20th November 2022.