Karen Westendorf is at the School of Art Gallery, Aberystwyth University to cast a critical eye over Unmaking the Modern: The Work of Stanley Anderson.

Those who do not have the pleasure of walking through the doors of the lovely Edwardian building that is the School of Art on a regular basis are often not aware that it houses an accredited museum and two public galleries that offer a great variety of – free – temporary exhibitions. One of these has just opened: Unmaking the Modern: The Work of Stanley Anderson (1884-1966).

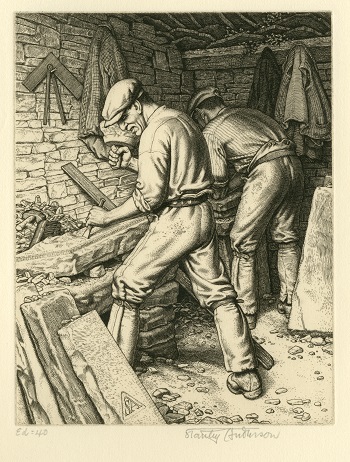

Stanley Anderson, RA, was a Bristol born and bred painter-printmaker. He trained as a professional engraver and became a lecturer at the Goldsmith College in London during the 1920s. He detested the modern age. Modernity, in his own words, was a return to ‘barbarism in ethics, childish perversity in the arts and baser ambitions in living.’ Hence, his works often conjure up a quaint world untouched by progress. There are a ploughman in the field (Three Good Friends 1950), a thatcher on the roof (The Thatcher 1944) and a cooper in his workshop (The Cooper 1947) looking by all means as if the technical acquisitions of the twentieth century had passed them by. But, as Head of School & Keeper of Art Professor Robert Meyrick explains, Andersen’s prints are never simply “nostalgic”. On the contrary, his depictions show people whose trades were fast disappearing, threatened by machinery that would take over their tasks and thus deprive them of their livelihood. Anderson’s urban scenes emphasize his concerns: Workers at Billingsgate are fighting for the chance of a day’s labour in Casual Labour, Billingsgate (1913), a ragged couple – cruelly called Venus and Adonis (1924) – are sleeping on the pavement and a Madonna of the Arches (1923) is surrounded by destitute old folks instead of adoring Magi. As the show’s curator, Dr Harry Heuser, points out: “In works like these, Anderson insists of making society’s disregard visible by letting the outcasts take centre stage.”

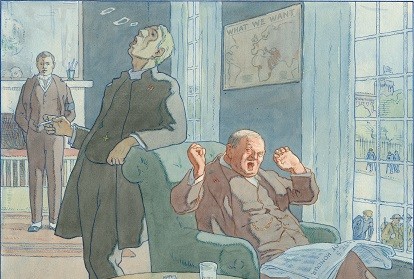

Although Stanley Anderson was mainly a printmaker, he also produced a series of satirical WWI watercolours during a career that spanned more than six decades. These images leave no doubt about what Anderson thought of the conflict. The Donors of Sons (header image, 1917), for example, forcefully demonstrates the huge financial gains that investors pocketed to the cost of millions of young men’s lives. These watercolours are on loan from a private collection and have never been seen in public before – not even during Anderson’s lifetime.

For anybody who is interested in rural and urban British life during the first half of the twentieth century, and for those who enjoy exquisite craftsmanship – Stanley Anderson hated the word ‘artist’ – this exhibition is a must-see. Heuser, who teaches art history and curating at the School of Art, “practices what he preaches” and created engaging and informative panels and labels that give necessary historical and biographical background, but also leaves space for the observer to make his or her own discoveries in the often incredibly detailed images. There is an excellent catalogue raisonné, written by Heuser and Meyrick, that is a joy to peruse and is available for sale at the special discounted price of £20 (RRP £30) at the School of Art’s office.

Unmaking the Modern: The Work of Stanley Anderson (1884-1966) is open until 11 March 2016 at the School of Art Gallery, Aberystwyth University. Many of the works previously formed part of Heuser and Meyrick’s successful show An Abiding Standard: The Prints of Stanley Anderson at the Royal Academy of Arts in London (25 February – 24 May 2015). The second gallery explores the works of Anderson’s students, such as Paul Drury and Graham Sutherland, at Goldsmiths’ College in An Exacting Taskmaster: Stanley Anderson and the Class of 1921 – curated by Meyrick – and should certainly be included in the visit.