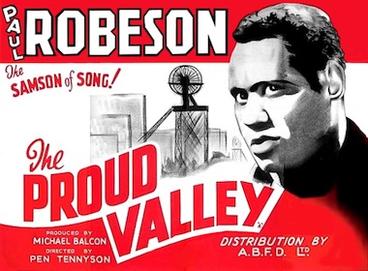

Phil Morris revisits Pen Tennyson’s The Proud Valley, the 1940 Ealing Studios film starring cultural icon and political activist Paul Robeson.

October 1957. A long-distance phone call links the Welsh seaside town of Porthcawl – where the South Wales miners have gathered for their annual Eisteddfod – to an undisclosed recording studio in New York, where Paul Robeson waits to circumvent his internal exile and the harsh restrictions placed upon him by the US authorities. The Miners’ leader Will Paynter introduces the legendary singer and activist with ‘warm greetings of friendship and respect’ and a hushed audience in the Grand Pavilion strains to hear the famed bass notes they had once thrilled to during the hungry thirties. Robeson speaks humbly of his ‘beloved Wales’ and then the public address system crackles with his electric rendition of the spiritual ‘Didn’t My Lord Deliver Daniel?’ His singing voice is at once familiar, and yet startling in both its musical power and its indignant yearning for freedom. The song has sprung from the experience of black slaves in America, but it resonates with oppressed peoples everywhere. The sense of working-class solidarity becomes irresistible when the Treorchy Male Voice Choir responds with the Welsh folk song ‘Y Delun Aur’ – made all the more poignant by the fragility of the transatlantic connection in this age before communication satellites.

October 1957. A long-distance phone call links the Welsh seaside town of Porthcawl – where the South Wales miners have gathered for their annual Eisteddfod – to an undisclosed recording studio in New York, where Paul Robeson waits to circumvent his internal exile and the harsh restrictions placed upon him by the US authorities. The Miners’ leader Will Paynter introduces the legendary singer and activist with ‘warm greetings of friendship and respect’ and a hushed audience in the Grand Pavilion strains to hear the famed bass notes they had once thrilled to during the hungry thirties. Robeson speaks humbly of his ‘beloved Wales’ and then the public address system crackles with his electric rendition of the spiritual ‘Didn’t My Lord Deliver Daniel?’ His singing voice is at once familiar, and yet startling in both its musical power and its indignant yearning for freedom. The song has sprung from the experience of black slaves in America, but it resonates with oppressed peoples everywhere. The sense of working-class solidarity becomes irresistible when the Treorchy Male Voice Choir responds with the Welsh folk song ‘Y Delun Aur’ – made all the more poignant by the fragility of the transatlantic connection in this age before communication satellites.

Robeson had been asked to sing at the same Miners’ Eisteddfod for each of the previous four years but was prevented from accepting these invites due to the revoking of his passport, which followed his frequent refusals to deny membership of the Communist Party. The US Supreme Court finally reinstated Robeson’s passport in 1958 – the South Wales miners having petitioned on his behalf. When Robeson appeared in person at Porthcawl later that year, he acknowledged the strong affinity that existed between him and the Welsh: ‘You have shaped my life – I have learnt a lot from you. I am part of the working class. Of all the films I have made the one I will preserve is The Proud Valley.’

The Proud Valley is not a classic film. It is not even a very good one. It is, however, a powerful document evidencing the deep spiritual bond forged between one of the most extraordinary cultural figures of the 20th Century and the Welsh working-class. The film is based on a story by the husband-and-wife scriptwriting team of Herbert Marshall and Alfredda Brilliant, who were both members of the left-wing Unity Theatre. Robeson plays David Goliath, a transient worker from the American south who has sailed to Cardiff and has jumped a freight train to the Welsh mining village of Blaendy in search of work. The name is suggestive of both the physically imposing Philistine Giant and the Hebrew underdog boy-king – and it identifies the character as emblematic of the strength and innocence of the honest working man.

David Goliath’s entry into the closed community of Blaendy is facilitated quite by chance; when he happens upon the local male voice choir rehearsing a religious oratorio he spontaneously accompanies them through an open window of the local working men’s club and is immediately recognised as the soloist who might win the first prize at the upcoming Eisteddfod. This scene would be seen as rather naïve and corny were it not for the elemental force of Robeson’s bass voice as it sings out the line, ‘Lord, God of all brothers!’

Perhaps the most interesting scene in the film takes place when local choirmaster Dick Parry finds work for David as his ‘butty’ down the pit. Parry’s fellow miners are openly critical of the decision, their opposition motivated by racial prejudice and concerns for their jobs. The choirmaster wins the argument by countering, ‘Damn and blast it man! Aren’t we all black down that pit?’ The line might seem an overly neat and simplistic response to such racially-aggravated animosity, and the miners seem to agree with the sentiment rather quickly to be credible, and yet, given the date of The Proud Valley, this firmly-drawn equivalence between white and black working-class men does seem quite radical even for the era of the Popular Front.

It is striking, on reflection, that Robeson does very little singing in the film, given his immense prestige as an international concert performer at the time. The singular musical highlight of The Proud Valley is Robeson’s singing of ‘Deep River’ at the funeral of Dick Parry – the choirmaster having been killed in a mining disaster. This performance would surely have brought to the minds of Welsh audiences Robeson’s frequent visits to Wales during the 1930s in support of miners’ causes. In 1938, he helped to dedicate the International Brigades Memorial at Mountain Ash, telling an estimated crowd of 7000 people, ‘I am here because I know that these fellows [33 men who had died in the Spanish Civil War] fought not only for me but for the whole world. I feel it is my duty to be here.’ Moreover, Robeson’s connection to Wales dated back to 1928 when, during his long West-End run in the musical Showboat, he met a delegation of miners who had walked to London to publicise their poor pay and working conditions following the collapse of the General Strike in 1926.

Despite its clear leftist politics, The Proud Valley is not a particularly gritty piece of social realism. The few scenes shot on location in the Rhondda Valley only serve to expose the artifice of scenes shot in the Ealing Studios against ersatz pit-head winding towers and improbably enlarged terraced houses. The social critique of the film is presented during a sequence in which a small group of miners, which includes David Goliath, march on foot from South Wales to London to convince a group of mine owners to reopen the Blaendy pit after the previous disaster has caused it to close. Images of Robeson tramping with his fellow miners in working-class solidarity are intercut with flying newspaper headlines warning of impending war with Nazi Germany. The message being, as the miners’ leader Ned explains later in the film, ‘Coal, at wartime, is as much a part of our national defence as anything else.’ Here the Welsh miners are allowed to elide their fight for economic survival with their fierce opposition to fascism, and Robeson stands visibly in support of them in both struggles.

The Proud Valley climaxes with the Blaendy miners attempting to reopen their pit through a previously sealed, and inherently dangerous, section of the mine. A gas explosion causes the old mine roof to collapse, thereby trapping a group of miners, including the choirmaster’s son Emlyn Parry. The miners are left with only one option to avoid their imminent death, and that is to blast their way to escape using a single stick of dynamite. This action necessitates that one of their number has to sacrifice his own life for those of his brothers, and the task is bravely undertaken taken up by David Goliath. The film ends with Robeson singing ‘Land of My Fathers’ over pastoral images of the Welsh countryside.

The nobility of David Goliath’s sacrificial act, with its obvious connotations of socialist brotherhood, was lost on several critics, particularly Graham Greene who wrote in The Spectator that the character was a ‘big black Pollyanna’ who kept ‘everybody cheerful and dying nobly at the end.’ This charge seems mean-spirited given the strength and depth of Robeson’s feelings toward the Welsh miners, and wrong-headed given the clearly delineated spiritual and archetypal dimensions of the character he was playing.

Furthermore, Robeson’s performance in The Proud Valley must be viewed in light of the actor’s continuing struggle to depict black people as complex and intelligent. As Robeson’s biographer, Martin Duberman, noted:

‘During his nearly twenty-year film career, [Robeson] tried time and time again to expand the limited vocabulary and representation of black life – even as he bore the brunt of denunciation by black newspapers and political leaders for accepting stereotypic parts. Often Robeson took a role only after having been promised that the film would have a progressive thrust – and would then discover, on seeing the final cut, that he had been misled or lied to.’

In The Proud Valley, Robeson certainly demonstrates his very limited acting range, but David Goliath is an intelligent, resourceful, proactive, politically committed and self-aware working-man. His self-sacrifice is motivated by gratitude towards an adoptive people who have recognised and valued his humanity. Moreover, Robeson’s substantial screen presence and unique singing voice ensure that his character is not portrayed as simplistic or stereotypical.

Criticism of the film also came from the right. Newspaper proprietor Lord Beaverbrook banned any mention of The Proud Valley in his Express newspapers when Robeson called on Britain and the US to support Soviet Russia in its fight against Hitler. The film flopped at the box office and became a curio that was seldom televised and only recently released on DVD.

The Proud Valley endures now as a reminder of the extent to which Paul Robeson’s supreme musical talent went hand in hand with his radical politics. As the son of a former slave, he appreciated the capacity of music to liberate the soul from the back-breaking and heart-breaking toils of manual labour. It is this knowledge that connected him, intuitively and politically, with the Welsh miners. He supported them during their greatest struggles, and they never forgot him as he faced persecution in McCarthy’s America.

It is sad to note that in 2013 – at the zenith of hip-hop’s worldwide popularity – that no contemporary black (nor white for that matter) cultural figure has dared to take on Robeson’s mantle as a global advocate for the oppressed. Now, when Jay-Z speaks to the disenfranchised and unemployed of the Rhondda, it is only because he parades before them the material wealth they aspire to with the hollow boast that he is ‘getting his.’ Vulgar self-regard and an obsession with making profit have turned mainstream hip-hop into a mirror of the capitalism that still oppresses black people in the ghettos of inner-city America and the Welsh youth growing up in post-industrial Wales.

The Proud Valley should be treasured, not as a time-capsule of pre-war Welsh mining life, but as a living testament to the values of Paul Robeson the artist and activist. Along with his recordings, its what remains of the man who was, by turns; a star college athlete, a law graduate, a populariser of gospel spirituals, the first black man to play Othello, and a civil rights leader.

As the Manic Street Preachers insist in ‘Let Robeson Sing’:

A voice so pure – a vision so clear

I’ve gotta learn to live like you

Learn to sing like you

Below is a link to Robeson’s telephone link-up with the Welsh NUM at Porthcawl in October 1957:

Banner illustration by Dean Lewis

Phil Morris has contributed regularly to Wales Arts Review.