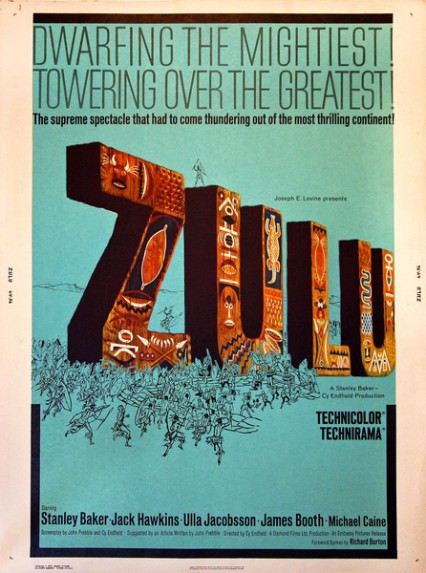

We look back at Phil Morris‘ 2013 exploration of the art of Zulu, Cy Endfield’s iconic cinematic telling of the Welsh at Rourke’s Drift.

Zulu is a perennial Christmas TV favourite: eminently quotable, it forms a matrix of reference points that facilitate a multitude of immediate intimacies between men – in particular, Welshmen – for whom the trials of war have, for generations, been experienced vicariously through schoolboy comics and Playstation video games.

The screenplay for the film was based on an article, one of a series on the topic of battlefield courage, written by the historian John Prebble, who peppered his subsequent script with occasional sideswipes at the savagery of colonial war. Such nods to the anti-war spirit of the nineteen sixties, however, sit awkwardly alongside the Kiplingesque thrills of imperialist adventure that provide the film with its dramatic and emotive charge. Zulu venerates the martial bravery and supreme self-discipline of an indigenous African people, but it is also an unabashed nationalistic celebration of the Celtic warrior spirit. One of the stranger aspects of the film is that, in spite of its title, the heroic function of the film belongs to a small contingent of redcoats who hold out against successive tides of nameless black hordes, whose voices are raised only in thunderous pre-battle chants. Stranger still, this imperialist myth was shot, almost entirely, on location in South Africa, and in full compliance with the apartheid laws, by a formerly blacklisted Hollywood liberal, Cy Endfield, and the Welsh socialist actor-producer, Stanley Baker.

The film is an enduring classic; expertly crafted, epic in scale, with enough attention paid to the delineation of complex characters to provide Stanley Baker and Michael Caine with career-defining roles. A supporting cast of brilliant character actors, including Jack Hawkins, Patrick Magee and Nigel Green, flesh out a gallery of memorable characters, most notably the latter creating an indelible impression as the steadfast Colour Sergeant Bourne. John Jympson’s innovative editing allows Cy Endfield’s assured direction of the action sequences to unfold with electric pace and all in sumptuous Super Technirama 70mm film. John Barry’s memorable and superbly-orchestrated score, which was inspired by recordings of Zulu music he had researched, amplifies the grandeur of the conflict and the Drakensberg Mountains where the film was shot. Both in creative and technical terms, Zulu is a formidable film-making achievement; yet it is this very excellence that should compel us to examine its ideological flaws.

The broad facts of the story are dramatised with reasonable historical accuracy. The film opens with the annihilation of a column of fifteen hundred British soldiers by an army of twenty-thousand Zulus at the Battle of Isandlwana. Later, that same day, a force of four-thousand Zulus is seen marching on Rorke’s Drift, an army station-post manned by a meagre force of Royal Engineers and members of the twenty-fourth regiment of foot. News of the earlier disaster, and the prospect of imminent death, prompt the two commanding officers to this sardonic exchange:

Lieutenant Chard: The army doesn’t like more than one disaster in a day.

Lieutenant Bromhead: Looks bad in the newspapers and upsets civilians at their breakfast.

These lines suggest that rather than being dedicated to the military and ideological aims of British imperial policy; both officers are estranged from their fellow countrymen by a curious blend of cynicism and fatalism – the eternal excuse of the soldier intended to absolve him of his crimes, I serve at her majesty’s pleasure. In a later exchange, a young private demands of his wise old NCO:

Pte. Cole: Why is it us? Why us?

Colour Sergeant Bourne: Because we’re here, lad. Nobody else. Just us.

The realpolitik of imperial conquest is thus glossed over with the soldier’s shrug: theirs not to reason why, theirs but to do and die. In contrast, the Zulu warrior does not even get to pose his question, never mind receive an answer. The single utterance of a black character in the film is made by King Cetewayo, with the order of summary execution of a warrior who has man-handled the daughter of his guest, the white missionary Otto Witt. The moment attests to Cetewayo’s immense power, but also to his otherness, his barbarity, his supposed lack of civilisation. Cetewayo’s political aims and emotional ties to his country remain unexplored, a mystery, they are unimportant to the screenwriters and film-makers. The voiceless grievances of the Zulus – who, let us not forget, have had their lands invaded by the British – loom in ominous silence over the film. No one appears interested in why they are fighting or why they have to be killed. The bravery of the Zulu is certainly acknowledged, even admired by the British (and the Boer Adendorff) but, ultimately, the presence of the Zulus serves only to contextualise the bravery of their Welsh enemy.

The silencing and over-simplification of the Zulu are given added bite by the casting of Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi in the role of his great-grandfather King Cetewayo. Buthelezi would later lead the Inkatha Freedom Party, which became notorious for its collaboration with the Afrikaaner National Party in its fight against Nelson Mandela’s ANC. Stanley Baker might not have predicted Buthelezi’s future political career, but according to Baker’s widow, Ellen, the Sandhurst-educated Buthulezi was ‘treated very differently by the [South African] government’ which should have given Baker some inkling.

The Sharpeville Massacre had taken place a week before principal photography. Ellen Baker maintains that the South African security police (BOSS) were present on set throughout the shooting of Zulu. Given this political context, and the strictures imposed on the producers by the apartheid regime, the casting of Buthulezi and the lack of dialogue in the film for its black characters, seems at best naïve, and at worst complicity. Perhaps the exigencies of film production contrived to dull Stanley Baker’s politically liberal instincts, as James Booth, who played the iconic Private Hook, recalled twenty years later, “It is fun when you’re boys playing at soldiers.”

Historical epics require a little artistic licence if they are to work as dramas, and the minor historical inaccuracies in Zulu will not be listed here, as most of them concern changes to certain characters’ backstories. Yet in one notable instance, the interpolation of an invented event, the paradoxical wrong-headedness of the film is vividly illustrated. Prior to a final charge, the Zulus begin a war-chant to summon up their bloodlust and intimidate their redoubtable enemy. Chard, played by Baker, approaches Private Owen, played by the Welsh singer Ivor Immanuel:

Lieutenant Chard: Do you think the Welsh can’t do better than that, Owen?

Pte. Owen: Well, they’ve got a very good bass section, mind, but no top tenors, that’s for sure.

In other words, the Zulus lack polyphony – they lack the complexity and sophistication of Western music. They also lack that other signifier of Western prowess, the Henry-Martini repeating rifle. For lacking both, the Zulus must die.

In the most celebrated scene of the film, the predominantly Welsh defenders of Rorke’s Drift break into a spontaneous and polyphonic rendition of the Welsh anthem Men of Harlech. There is no historical record of soldiers singing during the battle. Only fifteen per cent of the British soldiers present were actually Welsh. Over a third of them were English. The regimental song of the soldiers at Rorke’s Drift was, in truth, A Warwickshire Lad. The question then arises as to why Men of Harlech features so prominently in Cy Endfield’s film. A new set of lyrics for the song was written especially for Zulu. They are worth quoting in full:

Men of Harlech, stop your dreaming

Can’t you see the spearpoints gleaming

See the warrior pennants streaming

O’er the battlefield

Men of Harlech, stand ye steady

It cannot be ever said ye

For the battle were not ready — Welshmen never yield!

From the hills rebounding

Let this war cry sounding

Summon all at Cambria’s call

The mighty foe surrounding

Men of Harlech, on to glory

This will ever be your story

Keep these burning words before ye

Welshmen will not yield!

The original lyrics were written in the late eighteenth century and reportedly celebrate the heroic defence of Harlech Castle by Welsh soldiers under the command of Dafydd ap Ieuan from 1461 to 1468. Other sources claim it refers to another siege of the same castle, involving Owain Glyndwr in 1404. The important point to note here is that this song, which refers to anti-imperial resistance against the English, is sung by Welsh soldiers wearing the uniform of their colonial masters in the act of conducting imperialist aggression against people who are themselves expressing their resistance in song. In this crucial scene, Baker’s Welsh chauvinism has allowed him to present the defenders of Rorke’s Drift as Welshmen notionally protecting their little patch of Wales located in the middle of the Drakensberg Mountains. The station-post is no longer Zulu-land; it belongs to the Welsh who will defend it to the death.

Some may argue that John Jympson’s expert cross-cut editing between the opposing ranks of singing soldiers in this scene, establishes some form of moral equivalence between the two forces – their respective bravery appears to evoke some form of mutual respect. Yet while this spurious equivalence credits the Zulus with immense physical courage, it ignores their moral right to their land. The film climaxes with the Zulu army departing the field, but not before saluting their fellow braves inside Rorke’s Drift. No such salutation is mentioned in the historical records, and it’s most likely that the Zulus made a tactical retreat after spying a British relief column on its way.

Before the credits roll, the sonorous tones of narrator Richard Burton list the recipients of the Victoria Cross who fought in the battle, before Men of Harlech is reprised. The final words of the song boom out ‘Welshmen will not yield!’ The historical reality of the aftermath of the battle was more sordid and prosaic, as the historian Ian Knight describes: ‘When the battle was over, the garrison and relief column went over the field, and shot or bayoneted all the wounded Zulu they found there.’

There is one exchange in which the cruelty of colonial aggression is acknowledged:

Lieutenant Bromhead: …I feel ashamed. Was that how it was for you? The first time?

Lieutenant Chard: The first time? Do you think I could stand this butcher’s yard more than once?

Lieutenant Bromhead: I didn’t know.

Lieutenant Chard: I came up here to build a bridge.

This seems to be a rather disingenuous case of trying to have your cake and eat it. Baker’s Chard wants to distance himself from his role within the imperial military machine, whereas the historical Chard continued to serve for many years in the British army after receiving his Victoria Cross, as did Bromhead. Zulu tries to present both the British soldiers and Zulu warriors as victims of a one-off historical happenstance over which neither had much control, They appear to fight each other reluctantly, yet bravely – indeed as ‘fellow braves.’ The reality was genocide. Zulu is not an anti-war film, nor truly is it a historical epic, it is a cavalry western in the old Hollywood style, in which white men kill indigenous people in order to steal their land, and are deemed heroic for doing so.

The emotive power of Zulu, its ability to inspire within Welshmen a yearning for past military glories is largely attributable to the skilled filmmakers who made it. Yet Cy Endfield’s film stands as a warning about the insidiousness of those old myths of empire and conquest. It is also proof that even those with a progressive political and social consciousness can be tempted into sacrificing their values in the pursuit of telling a ‘good’ story.

Phil Morris is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.

Banner illustration by Dean Lewis.