Adam Somerset reviews Who-ology: Doctor Who: The Official Miscellany, a compendium full of behind-the-scenes facts about Cardiff’s favourite Time-Lord.

The occasion for the publication of Who-ology is clear, even if its audience is not. The first episode of Doctor Who was broadcast 23rd November 1963. Who-ology makes no mention of this anniversary but its publication must connect. If intended as part of the wave of commemorations it is a good book, but it is not good enough. Its creators have built themselves an escape clause by terming it a miscellany rather than a complete guide. But it is let down by an uncertainty of tone, misdirection and incompleteness.

The two authors are good on the historical record. They capture the sheer rapidity with which the Doctor made the leap from television into the cultural mainstream. By December 1965 he is already on a London West End stage in The Curse of the Daleks at Wyndhams Theatre. November 1st 1986 and he is in an Ice Show at Blackpool. Star Trek makes tribute in the episode ‘The Neutral Zone’ broadcast in 1988. A computer print-out in the programme has the clearly legible names of Hartnell, Troughton, Pertwee, Baker and Davison. The last is misspelled.

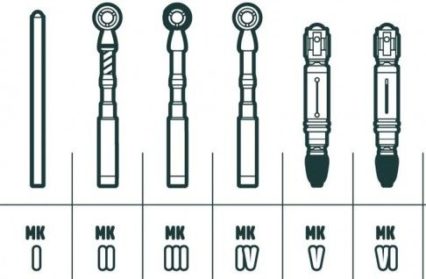

The Davies-Moffatt era may have been a great creative re-invigoration but the authors point to the debt that the new stewards owed to the many who have gone before. The sonic screwdriver, surprisingly, makes its first appearance 6th March 1968. Davros dates far back in time to 8th March 1975. A generation of viewers would have been unaware of the Autons. They were absent from 1971 until 26th March 2005.

Key moments in history are identified. 30th September 1978 marks the first script by Douglas Adams. K-9 has his own special programme 28th December 1981. On 30th March 1985 the Daleks are to be first seen hovering above the ground although it is brief. 5th October 1988 and they have acquired the power to ascend a flight of stairs.

by Cavan Scott and Mark Wright

BBC Books, 374 pp

All history has its moments of irony. The book quotes ‘The Daleks make what is intended to be their final appearance’. The date is 1st July 1967 and Terry Nation wants to spin them off for their own show and is in talks with US broadcasters. The Daleks consequently vanish for five years.

The end of the 1970s was not just piled-up mortuaries and mounds of rotting rubbish, an age for a twenty-first century audience as remote as anything that ever happened on Gallifrey. Both BBC and ITV are racked with industrial dispute and filming of ‘Shada’ is officially abandoned 10th December 1979.

But the Last of the Timelords is nothing if not indefatigable. Within a short space of time the Doctor is reincarnating on the hot new technology platforms. ‘Revenge of the Cybermen’ is released in October 1983 in VHS, Betamax and Video 2000 formats. On 13th November 2003 the ‘Scream of the Shalka’ goes out as an animated webcast.

The authors are relentless in detail, to sometime small purpose. The three hundred and sixty-two hours, fifty-three minutes and fifty-four seconds of broadcast time are converted to their seconds, one point three zero six four million, if anyone cared. Of the many companions we learn that eight percent were stowaways, six percent kidnapped and fourteen percent forced upon the Doctor. The sonic screwdriver has ninety-one applications, its last being to open a bottle of champagne on the ‘Voyage of the Damned.’

The Doctor’s myriad disguises are listed right through to a Punch and Judy Man in the ‘Snowman’. The reader learns that he is skilled at cricket, once taking five wickets. His specialty is a chinaman, a left-handed googly. He does not care for apples, bacon, yoghurt and a whole lot else. He once made the claim to be half-human on his mother’s side. His normal temperature is sixty degrees. He is intolerant to aspirin, and had a myopic right eye in his fifth incarnation.

And to the demerits. There is a natural focus on all things Dalekoid. The Master gets four whole pages to himself but the Absorbaloff, the Slitheen, the Pit, and the Family of Blood are absent. The section on the TARDIS omits that Peter Cushing in 1965 (feature film Doctor Who and the Daleks) dropped the ‘the’ and called it plain ‘TARDIS’. The editors have passed on the chore of providing an index.

In place of completeness the book goes in for some true barrel-scraping. They carry a pointless report as to which Doctor Who actors appeared in which of the Carry On series. Alexei Sayle, for instance, (‘Revelation of the Daleks’), appeared in Carry on Columbus. The authors do the same with the cross-over of actors who have appeared in Bond films, Coronation Street, Emmerdale and the Archers.

It is the kind of approach where theatre experience is dropped from actors’ biographies. Louise Jameson was stunning in the first production of Peter Nichols’ ‘Passion Play’. But this is a world where Doc Martin is more significant than Peter Nichols. The David Tennant CV skims over the theatre. He was on a West End stage at a young age in Kenneth Lonergan’s Lobby Hero in 2002. Given the infatuation with screen the book misses out that a young Carey Mulligan appeared in one of the very best episodes 7th June 2007.

The incompleteness is one aspect but the tone unsettles. It feels like a couple of jobbing authors doing a conglomerate’s project. They declare that Who-ology is a love letter to one of the craziest shows on television’. ‘Crazy’? They like ‘crazy’. The are on a ‘crazy, wibbly-wobbly, timey-wimey journey’. ‘Timey-wimey’ is an adjective they like too, as it is used more than once.

There may not be an index but acknowledgements go to a helper with the brackets (‘he knows why’). Family members are cited ‘for support and cups of tea’. Among the forty ways to defeat a Dalek number thirteen reads ‘Cause a civil war on Skaro. It’s the final end. (Hint: it isn’t.)’ The illustrations lack distinction.

Awe and thrill, reverence even, are absent. The scenes of ‘Mummy, please let me in’ from ‘the Empty Child’ are not just great television but transcend the narrowness of genre to stand alongside horror greats. Those hospital beds where the patients all sit upright go unmentioned.

A tale from 2007, which I have since heard repeated many times in different variations; a Saturday night anniversary dinner means that the baby-sitter is left at home with the usual instructions – television and bed at nine. Mid-meal, the parents take an emergency call to say that things are not good at home, not good at all. On their hurried return they find three children white of face. The Weeping Angels have arrived in their sitting-room.

Who-ology does facts but not true affection. Kitchen plungers were borrowed by the tens of thousands, so that kids could press them to their forehead and glide about threatening one other with extermination. Mothers were enjoined en masse to serve fish fingers with custard. And they did.

The end of November is going to see events and celebrations. Whether it is a worthy cultural celebration or just television industry introspection is personal judgment. There are a lot of commemorations. The creativity and accomplishment that emanated in particular from the Cardiff period were remarkable. Set against that Who-ology sits awkwardly. It is a corporatised initiative that lacks the beating heart, the understanding, the love even for what has become public television’s most enduring creation.

Adam Somerset is an essayist and a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.