St David’s Hall, Cardiff, 1 March 2016

Music by Grace Williams

BBC National Orchestra and Chorus of Wales with choristers from Ysgol Gerdd Ceredigion / National Youth Choir of Wales

Conductor: Tecwyn Evans / Trumpet: Huw Morgan / Soprano: Fflur Wyn / Mezzo: Catherine Wyn-Rogers / Tenor: Andrew Rees / Bass: Jason Howard / Narrator: Dr Rowan Williams

Prichard-Jones Hall, Bangor University, 4 March 2016

Music by Hilary Tann, Mared Emlyn, Sarah Lianne Lewis, Lynne Plowman, Rhian Samuel

BBC National Orchestra of Wales in association with Tŷ Cerdd and PRS for Music

Conductor: Tecwyn Evans / Soprano: Ruby Hughes

School of Music, Bangor University, 5 March 2016

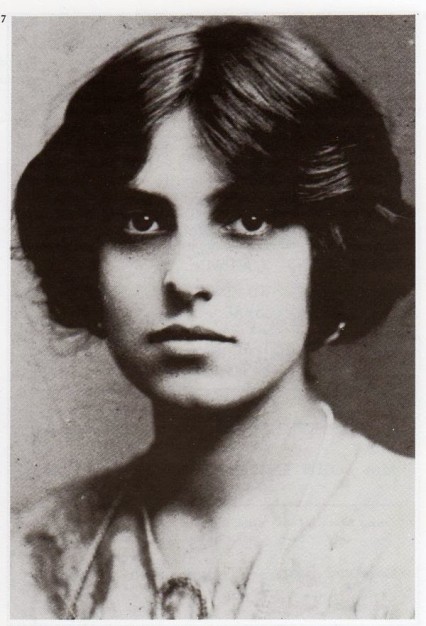

Discover Welsh Music: Dilys Elwyn-Edwards, Morfydd Llwyn Owen

Tŷ Cerdd Conference

Speakers: Gwyn L Williams & Dr Rhiannon Mathias / Soprano: Ellen Williams / Piano: Brian Ellsbury

To compose music is to do something off the beaten track, even if you’re a man. But if you’re a woman composer it is considered very odd indeed.

Grace Williams, 1960

It is nearly sixty years since Grace Williams uttered these words, in a talk for the Welsh Home Service. Interviewed sixteen years later, in 1976, the year before her death, she was adamant that she had experienced ‘no prejudice against us [female composers] at the [Royal] College [of Music], and there was no prejudice here in Wales either.’ Yet her friend and fellow student, Elizabeth Maconchy, was passed over for the Mendelssohn Scholarship on the grounds that – according to panel Chair, Sir Hugh Allen – ‘you will only get married and never write another note’. And she herself had gone on to comment, in 1961, that she envied the male composer’s ‘freedom to write a molto barbaro movement and have it regarded as just part of his nature and not in any way abnormal.’ The line between prejudice and deeply entrenched conservatism is, it seems, a fine one.

There is no doubt that Williams enjoyed the admiration and respect of colleagues and audiences, and her music was often lovingly performed by the then BBC Welsh (later Symphony) Orchestra and many others. In the Wales of her youth, where music-making lay at the heart of an inclusive community life, people were not so surprised at a female musician choosing to add composing to her other activities of arranging, singing, performing or teaching. Yet it is equally true that, more widely, the hidebound social and musical attitudes to which Williams so diplomatically alludes remained an obstacle to her, as they did to other women composers. On the social level at least, those attitudes have since proved slower to shift than is often assumed.

In terms of stylistic freedom, times have changed immeasurably for the better for composers of all sexes, with a gamut of musical expression available in an age of artistic pluralism. Few would now dare to offer the opinion that women should not write loud or boisterous music since it was ‘unfeminine’ to do so, which judgement regularly befell Ethel Smyth as well as the later Williams and many others. But it is not so long ago that Michael Vyner, then artistic director of the London Sinfonietta, in the mid-eighties declared on national radio that there were no ‘great’ women composers since ‘women can’t compose’. Bigotry aside (and there have been others who, like conductor, Vasily Petrenko, have more recently voiced equally unfortunate opinions regarding women on the podium), whatever the complex reasons may be, the number of women composers relative to men is improving at a frustratingly slow rate: in 2013, no woman composer won a BASCA award. According to Women in Music, who conduct a yearly survey, at the 2015 BBC Proms, works by women made up 10% of performances. This is an increase from 4.1% in 2010 but, whilst there were 24 pieces by living male composers of 15-minutes or longer duration, no work by a living woman composer was longer than 12 minutes – and just three women composers had works played in a main, evening concert. These and similar such statistics across the profession make sobering reading.

Of course, few if any women composers want to be selected or commissioned simply because they are female (myself included); indeed few welcome being labelled a ‘woman composer’ as opposed to simply being a ‘composer’. Whilst on a personal, professional level gender seems for many no longer an issue, composers’ opinions are naturally diverse regarding the causes of and possible solutions to the ongoing gender imbalance. As a culture, our unhealthy obsession with music of the past clearly plays a role in that, historically, far fewer women than men have had opportunities to compose – or indeed seriously to pursue any form of artistic expression – and so are bound to crop up less frequently in mainstream programmes. Composers are reliant upon performance opportunities which in themselves constitute a form of public validation. However, the quality of a performance – as Williams found to her cost with the Missa Cambrensis, following its reportedly dire premiere in 1971 – can have enormous consequences regarding a work’s future for good or ill.

In her thoroughly engaging lecture for Tŷ Cerdd’s ‘Discovering Welsh Music’ seminar at Bangor University on March 5, Williams expert Dr Rhiannon Mathias pointed out that it was only in the 20th century that women began to gain access to professional musical training, much less professional opportunities to compose. Perhaps, one might be tempted to think, it is simply a matter of time before women ‘catch up’?

Yet women have always written music – it’s just that we have been very bad at valuing and preserving it in a culture that continues to view large-scale symphonic works as the pinnacle of intellectual achievement within a hierarchy of ‘great masterpieces’. That said, there has never been a shortage of ambition amongst women composers to write music for large forces, orchestral or otherwise – and Grace Williams is one who emphatically achieved that goal. More recently, Rhian Samuel was one of five exciting Welsh or Wales-based contemporary women composers featured in a superb concert by the BBC National Orchestra of Wales at the Bangor New Music Festival on March 4, explored below. Samuel is also a musicologist who, in 1994, co-edited with Julie Anne Sadie the Norton/Grove Dictionary of Women Composers which details over 900 individual entries from western music history, many of whose music is yet to be fully documented, let alone heard beyond small enclaves of enthusiasts.

In Wales, Tŷ Cerdd is aiming to rectify a dearth of legible scores, recordings and freely available information with the announcement of a new, digitised archive in partnership with the National Library of Wales and Faber Music Publishing: DiscoverWelshMusic.com. Of eight major Welsh composers forming director, Gwyn L Williams’ initial two batches of composers, three are – or were – women: Grace Williams, Morfydd Llwyn Owen and Dilys Elwyn-Edwards, the last of whom was renowned for the English- and Welsh-language art song in which she chose to specialise almost exclusively. That Elwyn-Edwards and the tragically short-lived Owen wrote exquisite miniatures was evident at Mathias’ talk, which incorporated poignant live performances by soprano, Ellen Williams and pianist, Brian Ellsbury.

***

Cultural traditions are integral to the life of any community. But how these are celebrated and renewed tells us a great deal about attitudes to the present as well as to the past, since events can so easily become opportunities for nostalgia rather than honest assessment and a springboard to the future. So it was marvellous to see the BBC National Orchestra and Chorus of Wales bravely eschewing more populist daffodil-waving on St David’s Day to emerge triumphant with an all-Williams programme at St David’s Hall, which built to a rousing performance of that very same, immensely challenging Missa Cambrensis; only the second since its disastrous underestimation by the forces gathered at Llandaff Cathedral, 45 years ago.

Since then, the work has acquired a near-mythic aura, and it remains unique within the Welsh choral repertoire: a lengthy setting of the Latin Mass, incorporating a Welsh-language carol and spoken Beatitudes, employing a gargantuan chorus and orchestra interspersed with intense chamber writing at often relentless, full expressive tilt. The idiom is knottier than the other works in the programme might have led one to expect: first the Fantasia on Welsh Nursery Tunes (1940), an early work and Williams’ best-loved, then her intriguing Trumpet Concerto, written in 1963 for an instrument she clearly adored. Both were given excellent performances here (plaudits especially for the sonorous playing of soloist, Huw Morgan), before we stepped into the darker, more dissonant world of the Missa, with its lush, post-Vaughan Williams modality tempered by Bartókian tritones, falling minor seconds and a pounding ritualism which brought Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms to mind.

Whether Williams might have revised the piece, had she been able to bear revisiting it following the 1971 debacle, is open to debate. But she would surely have been proud to witness the commitment and musicianship on display at St David’s Hall on March 1, including that of the young singers of Ysgol Gerdd Ceredigion and the National Youth Choir of Wales, under the firm guidance of conductor, Tecwyn Evans. Of the four, spirited soloists, soprano Fflur Wyn rose especially to the occasion with soaring beauty of tone, whilst narrator, Dr Rowan Williams lent ecumenical weight to a work strongly felt, albeit composed by an atheist. The sheer force of the piece was more terror and anguish than supplication, and the choir showed magnificent determination throughout.

***

Three days later, three generations of contemporary composers gathered for another special concert, preceded by a panel discussion chaired by myself before a live audience at the Bangor New Music Festival, as part of a Tŷ Cerdd celebration of Welsh women composers. The event featured five diverse pieces, whose composers were present to hear their music performed by the BBC NOW, again on fine form under conductor, Tecwyn Evans, and joined this time by the eloquent soprano, Ruby Hughes.

Hilary Tann was appointed the first ever Tŷ Cerdd composer-in-residence, from 2014-15. She and Rhian Samuel are contemporaries, both born in the 1940s in South Wales but who have both since moved away, earning distinction elsewhere as academics as well as composers. Each represents a different facet of a postwar generation for whom being a ‘woman composer’ remained a battleground despite the explosion of youth culture and social activism in the sixties. Lynne Plowman (born in 1969) first came to Wales to study at the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama, where she now teaches. Renowned for her award-winning youth and community operas for Welsh National Opera, Glyndebourne and others, she is part of the first wave of composers fully to experience the benefits of that activism and the trail blazed by women composers before her. In turn, she herself has now become a figure of inspiration for young composers, of whom Mared Emlyn and Sarah Lianne Lewis are two who show great promise, having embarked on professional careers following recent studies at Bangor and Cardiff University respectively.

Tann’s The Open Field commenced the concert in a vigorous, full-bodied fashion which would endure for the evening in various guises. Composed in 1989 for the Schenectady Symphony Orchestra in New York State, USA – her home for some years – this was the first time the piece had been performed in Europe. Impressive in its combination of bold fanfares with intense, almost Sibelian lyricism, the work’s dramatic, military allusions felt sombrely moving in the light of Tann’s dedication ‘in memoriam Tiananmen Square’. Tann has never ceased to feel close to nature and the Welsh landscape – which also provided inspiration for Emlyn’s Porthor (Whistling Sands); a BNMF commission here receiving its world premiere. Named for the famous ‘singing sands’ of the Llŷn Peninsula beach, this assertive piece revealed an ear sensitive to harmony as well as colour, and the occasional, wry rhythmic gesture á la Shostakovich.

Lewis took us into more avant-garde territory with Is there no seeker of dreams that were?: the second of three world premieres, and a piece full of imaginative sonorities involving bowed percussion, agitated woodwind, fast, glissandi strings and more. Inspired by Cale Rice Young’s poem ‘New Dreams for Old’, and dedicated to the memory of her grandmother, Lewis’ sudden swerve into more diatonic, melodic writing was arresting towards the close.

Completing the first half of the concert, Plowman’s Catching Shadows is the first finished piece to bear the fruits of her work with Harrison Birtwistle under a 2012 Arts Council of Wales Creative Wales Award. The result is a thrilling muscularity and sureness of design, with material developed from small motifs and cells atop underlying, contrasting pulses. Through a series of sections in evolving tempi, pointillist woodwind were interrupted by brassy outbursts and angular strings, with some lovely, sustained harmonic writing for the latter in particular.

The second half was devoted to Samuels’ Clytemnestra, a rich, substantial piece from a composer plainly at ease with both her material and her own voice. The piece was written for the BBC NOW in 1994, and the orchestra here in Bangor clearly relished its strong, colouristic writing and expressionist contours. In seven scenes, the vocal narrative and orchestral support alike were deftly succinct in portraying the agony, violence and grief of Aeschylus’ wronged yet ambivalent heroine. Hughes sang beautifully; by turn, chilling and heartrending in short, poetic imagery and longer melismatic lines. This was word-setting of the first order – and a vivid, powerful way to end a concert celebrating women whose creative endeavours would have been seen as a challenge to society itself not so very long ago.

The Bangor New Music Festival concert by BBC NOW is broadcast today, Tuesday 8 March 2016, on BBC Radio 3 at 2pm, part of the day’s focus on women composers for International Women’s Day. Thereafter available on BBC iPlayer.

The Grace Williams BBC NOW concert was broadcast live from St David’s Hall on St David’s Day, 1 March 2016, and is available now on BBC iPlayer.

You might find this recent interview with Elena Langer of interest: composer of the critically-acclaimed Figaro Gets a Divorce for Welsh National Opera, currently touring.

Images courtesy of Tŷ Cerdd, Discover Welsh Music and the composers.