Penny Simpson looks at National Book Award-winner Patti Smith, as she revisits the most sacred experiences of her early years in Woolgathering.

Patti Smith’s memoir is quite unlike any other I have ever read. Her life story isn’t presented in neat chronological order, nor is it a familiar rites-of-passage tale. Instead, she provides an extraordinary account of a child’s evolving imagination, illustrating in vivid images and circular musings how that feeds into the inspirations retained by her older self living in a street of cafes in New York. It’s close to poetry, drawing on repeated motifs which circle and spin throughout this slim volume like the moth’s wings she seems so drawn to and frequently cites as a point of reference when trying to pin down her childhood dreams and the fragmented reality she experiences as a young writer following in the footsteps of her idol, the French poet Rimbaud.

The memoir is close to incantation, drawing as it does on a series of objects that link past and present. The marbles she plays with as a child, ‘small glowing planets, each with its own history, its own will of gold’ are echoed in the ruby jewel from India she keeps in her sack of precious possessions in the city, ‘imperfect, beautiful liked faceted blood.’ Staring at this ruby, she’s reminded of its origins, washing up on a faraway shore, ‘gathered by beggars who trade them for rice.’ The ruby is lost one day, but its talismanic properties prevail: ‘I can feel the dust of Calcutta, the gone eyes of Bhopal. I can see the prayer flags flapping about like old socks.’

by Patti Smith

80pp, Bloomsbury, £10

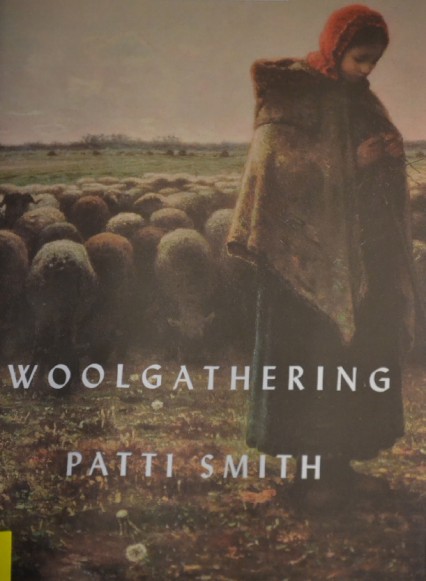

The woolgatherers referred to in the book’s title are its connecting thread. These are dreamlike figures she first sees as a child, sitting up in bed at night, staring out of her window towards a field beyond her family home. The woolgatherers are named by Harry Riehl, the man who sells minnows in town, a strange sage-like figure the young girl seeks out to help ground her imaginings. ‘I used to think I could see the white of their bonnets and, at times, a hand, the act of grasping.’ She designs cloaks and boots for these strangers, and imagines them occupied with ‘no task more exceptional than to rescue a fleeting thought, as a tuft of wool, from the comb of the wind.’ The woolgatherers are like artists, plucking at the fragments of existence and re-assembling them in some mysterious and wonderful way.

One of the few factual references included in the memoir relates to Patti Smith’s great-grandmother, who was descended from a long line of Norfolk farmers and solitary shepherds. ‘I possessed the soul of the shepherdess,’ she acknowledges. ‘Through her I was drawn to the dreamers’ life.’ Later, she writes about a journey through a street of cafes in New York, a highly charged voyage where she starts as a body double for the drunken poet in Cocteau’s Orphee then mutates into ‘a solitary shepherdess gathering bits of wool plucked by the hand of the wind. Twittering threads caught in the thorns of an icy branch.’

The theme of this book is the gift of imagination, a gift the writer clearly associates with the figure of the shaman, as well as the woolgatherer, one that is fragile and fleeting but which shapes and inspires across all the decades of a life. This is her subject matter, not a roll call of the people met, or a literary re-enactment of past events. She gives this expression through a closely woven web of personal inspirations and talismans, intercut with archive photographs and an occasional fact, usually someone or something familiar to anyone who has read her autobiography Just Kids, including the writer Sam Shepherd and her ‘absurd’ but ‘adored’ rubberised, green kelly taffeta raincoat. It might not be memoir as we know it, but it’s probably closer to a true rendering of a life lived than a more self-conscious prose full of polished anecdote. It’s like eavesdropping on a stream of consciousness, but one underpinned by an eye for the exceptional detail. My advice: slip it in a pocket, head for the nearest field and join the woolgatherers.