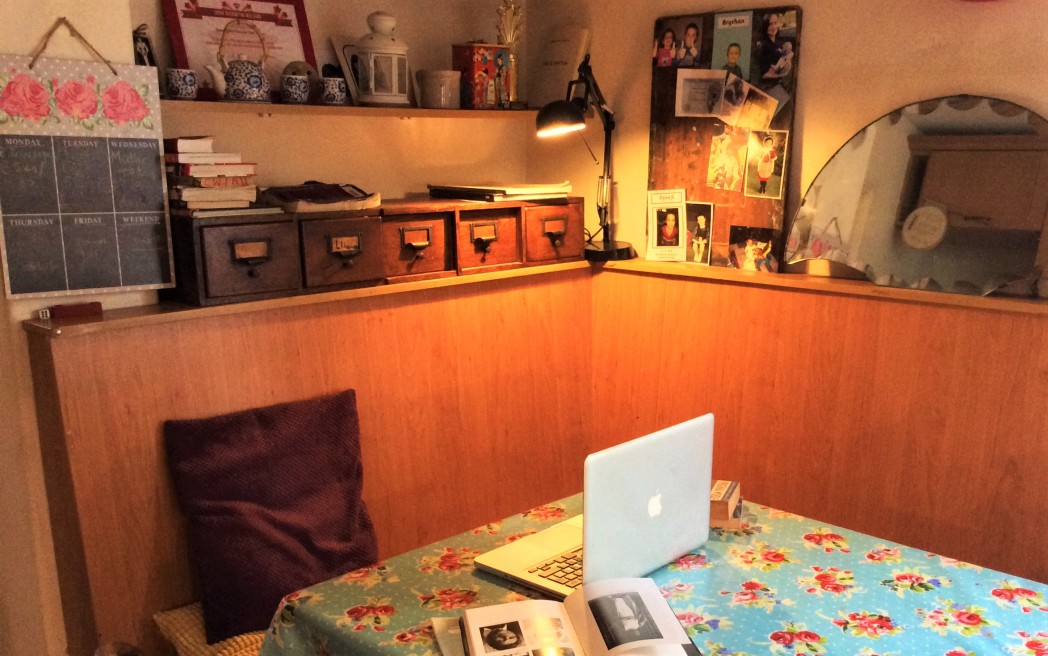

I often write in a corner of the kitchen surrounded by some of my favourite souvenirs. These include a red tea tin from 1940s China brought back by my great-aunt, Menna Wilders, who was the inspiration for my novel The Rice Paper Diaries, a sparkly plastic trophy my son won in a poetry competition, and my mother’s wooden easel from when she was a student at St Martins in the 1960s, which has more pinholes in it than I can count from where she used to fix her paper to the wood. On the shelves behind the table are a china gravy boat from an old family home near Capel y Wig in Ceredigion and a blue-and-white tea set I bought in Shanghai last year, among other precious mementoes.

I wouldn’t say I’ve perfected the art of working with my family around me, but I have got better at it. I sometimes feel like a character in a Shani Rhys James painting, surrounded by the detritus of her art-making – gloves, paintbrushes and so on (although in my version these are more likely to be lost socks and phone chargers) – and an array of family members of different ages and genders who are all just there, looking out of the canvas at the viewer. Comfortingly, the one thing Shani’s work never features is an empty canvas. That’s partly why I love her paintings so much – they exude the full, unnerving force of creation in apparently tame domestic surroundings.

When I was at a critical point in the writing of The Rice Paper Diaries, the children were still quite small and I had to burrow right back into the night hours to find a quiet time to write. I used to get up at five in the morning and write until my husband went to work at eight-thirty. Now that the children are older and more independent I try to be as flexible as possible. If I can’t take those few early hours at the kitchen table then I will write, read or think on my commute to and from Swansea University, where I teach. Even if I’m just walking down Cowbridge Road to pick up my daughter from school I’m always watching what’s going on around me on the pavements outside the pawn shops (and the porn shops), the bakeries, the garage on the corner, listening to passers-by speaking Welsh, Somali, Polish, Urdu, English and other languages.

My daily walks are somehow an extension of my writing time, and they are more important to me than having a room of my own. Even in the house itself, I’m much more peripatetic than this static picture suggests. I can perch in different corners, some of them piled up with books, others with toys, a table-tennis table, a piano, an X-box, a sewing machine. If I need access to the internet, or to dip into a book, I walk around the house until I find what I want – at the moment I’m reading a novel by French author Amélie Nothomb to review, and ‘The Embassy of Cambodia’ by Zadie Smith in preparation for an MA session on the short story, and George Saunders’ Tenth of December, just because I want to. I really like his stories, that hyperreal American mindscape he writes about. My husband writes too, so we do our best to give each other mental space. He often works at the kitchen table like me, or a desk in the bedroom, while family life is going on around him.

When I’m pulling a longer piece together, or working on anything beyond a first draft, I start to crave peace, and at that point I’ll head for the nearest cafe with my laptop. Once I start writing, everything else falls away. I think it was Anne Enright who said that ‘the Tao of writing is to write’, and I think she’s so right – it’s crucial just to get on with it, as and when and where you can.

Francesca Rhydderch’s Writers’ Rooms piece is a part of a Wales Arts Review series.