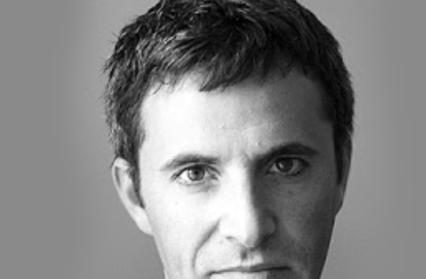

In the latest of our series taking a peek into the creative spaces of Wales’s leading authors, award-winning writer Tristan Hughes shows us his cabin in the woods.

When I was younger, I used to imagine writers’ rooms. They were romantic places; often housed somewhere in the nineteenth or early twentieth century, high up in garrets, along streets in bohemian quarters, around the corner from smoky cafes. I pictured them as repositories of long and marvellous accumulation – filled with great heaps of paper, piles of leather-bound books, a whiff of opium in the air, wine stains on the table. It seemed to me that toiling pens and quills must leave a kind of creative residue behind, a magic dust that settled over the years. But, like so many other imagined versions of a writer’s life, it didn’t quite turn out that way for me. My writing self has been more like a naked crab scuttling along the beach in search of shell. My books have all had different homes. There was a leaky caravan on Anglesey, a fishing shack in northern Ontario, an apartment in Minsk, and on and on. I’ve written in a lot of temporary rooms, but I’m lucky to be more settled in one now – for part of the year anyway. This room is in a little shack on the shore of a lake I’ve known all my life (my family has a cabin on the other side of the bay). In a way it is also temporary, but for other reasons: the shack is so rickety and ramshackle that despite (or possibly because of) my clumsy efforts at renovation, the winter snows could bring it down at any moment. The room will leave me before I ever leave it. There’s a nervous moment each time I arrive in the summer. Is the shack standing? Is it still there?

The lake and the shack in many ways do, quite literally, govern my writing days. There is no electricity for a start. I have a small solar panel that powers my computer and one lightbulb; on sunny days I might have enough charge for the whole day, on overcast ones I might have only a few hours’ worth. Clouds focus my attention, make me concentrate, get my fingers typing faster. Behind the shack, a railroad track snakes around the bay and on into the wilderness. Very few trains go by, often only one a day, but these tend to be at some point early in the morning and act as my alarm clock. Startled awake, I’ll lie in bed and listen. Once the sound of the train has passed, the lake will tell me what kind of day it is. I can tell from the volume and rhythm of the waves lapping the shore if there’s a breeze and how strong it is. These sounds will be there while I’m writing and, because the working mind pays a secret attention to such things, at the end of the day there’ll be a trace of those rhythms in my sentences. If there are no waves, and hence no breeze, then it’ll be a perfect morning for fishing, so there won’t be any sentences.

I’m only really a visitor in the shack, a guest of sorts. Two squirrels and a chipmunk have permanent possession. Safely settled in the rafters, they allow me to make use of the unused spaces below. A large garter snake likes to sunbathe on the rock outside the door. An eagle carries fish to its nest on one of the two islands I can see through the window. At night, the loons come into the bay and begin their laments. And I suppose I’ve been a visitor in other ways too. For in many of those writing rooms from my past, what I was conjuring, or remembering – and what after all is the difference? – was here.

In the winter, the lake is inaccessible by car or truck. You can only get to it by snowmobile. I went there once in January and discovered everything exactly as I’d left it in the autumn. There was a pencil on the table, a mug of half-finished, and hard-frozen, tea. The only difference was that every surface was covered in a rime of frost, full of bright and tiny points of sparkling light, a daytime milky way in miniature. I think of it often, from far away, glistening unseen on such winter days. Some part of my imagination remains there, as it always has. And I suppose that is an accumulation too, the residue of a long habitation, a kind of magic dust.

Tristan Hughes’s latest book, Hummingbird, is available from Parthian.

Tristan Hughes’ Writers’ Room piece is a part of a Wales Arts Review series.